King tides are arriving in California. Here’s what they can tell us about rising sea levels

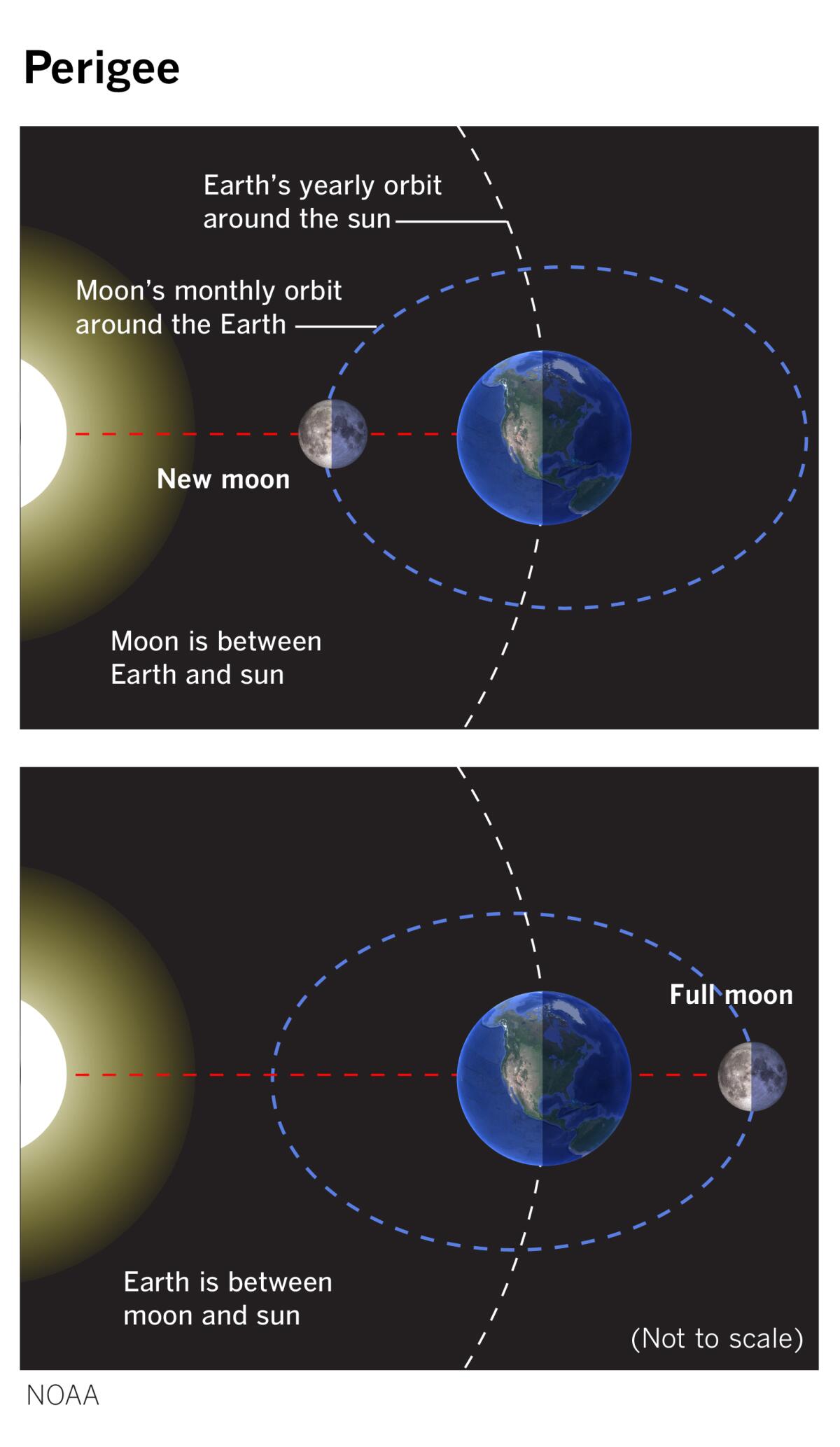

King tides are the highest tides of the year, but scientists have a different name for them: perigean spring tides. The name doesn’t refer to the season of the year — along the California coast, the most dramatic tides often occur in the winter — but to the “springing forth” of the tide during the new and full moon.

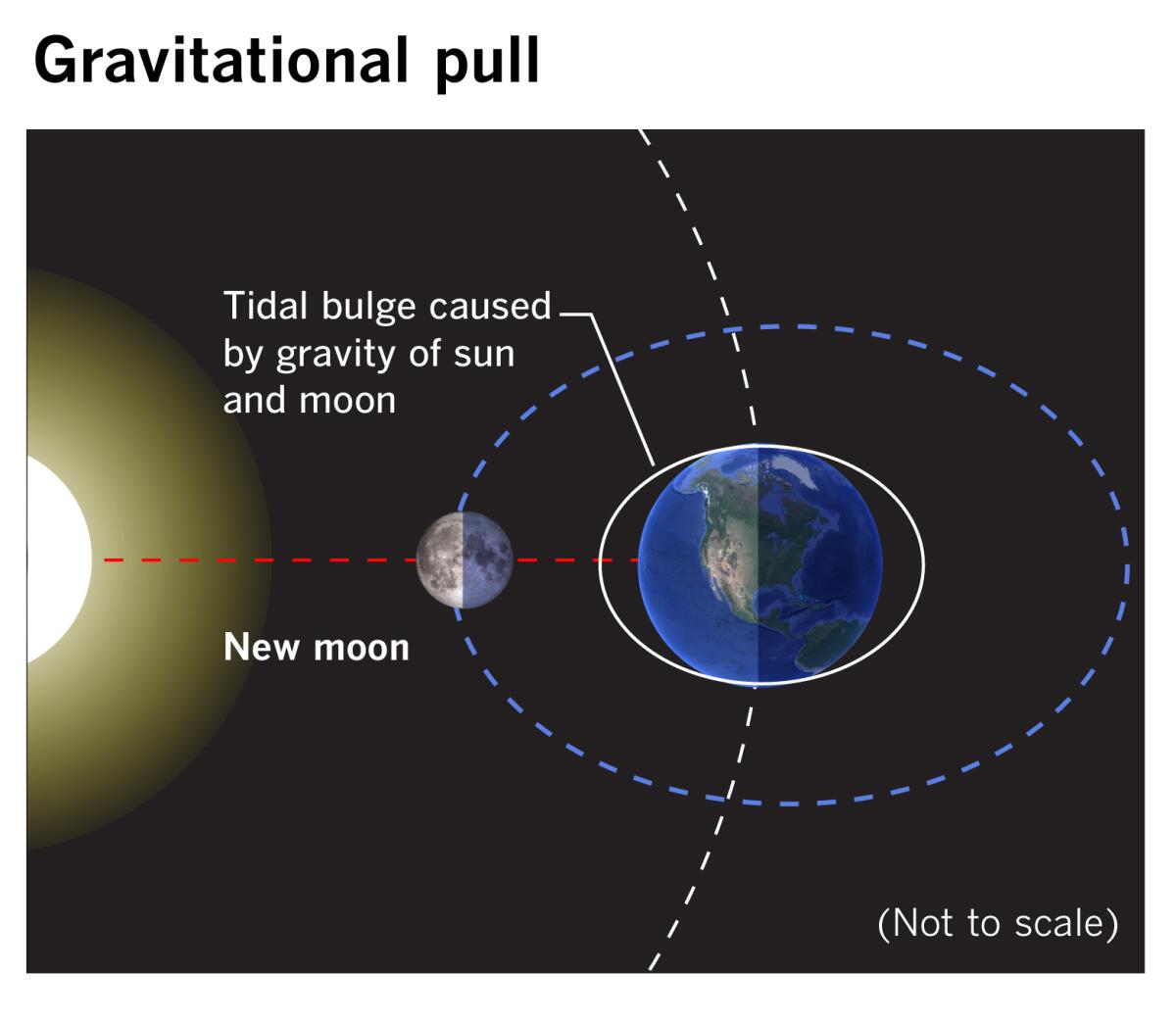

Tides are caused by the gravitational pull of the moon and the sun on the world’s oceans. During full or new moons, Earth, the moon and the sun are nearly lined up, pulling together to make the oceans bulge slightly more.

When aligned, the sun’s gravity is added to that of the moon. The sun is much bigger than the moon, but its gravitational pull is only half that of the moon because it is so much farther away. The combined pull of the sun and the moon on the oceans creates spring tides: higher-than-average high tides and lower-than-average low tides.

But the moon’s orbit of Earth isn’t a perfect circle. It’s slightly elliptical. So once about every 28 days, the moon passes a point where it is closest to Earth. In that position, known as perigee, the moon exerts its strongest gravitational pull, and the difference between high and low tides is the greatest.

When the new or full moon coincides with or is close to perigee, usually six to eight times a year, the result is a perigean spring tide, or what is popularly called a king tide.

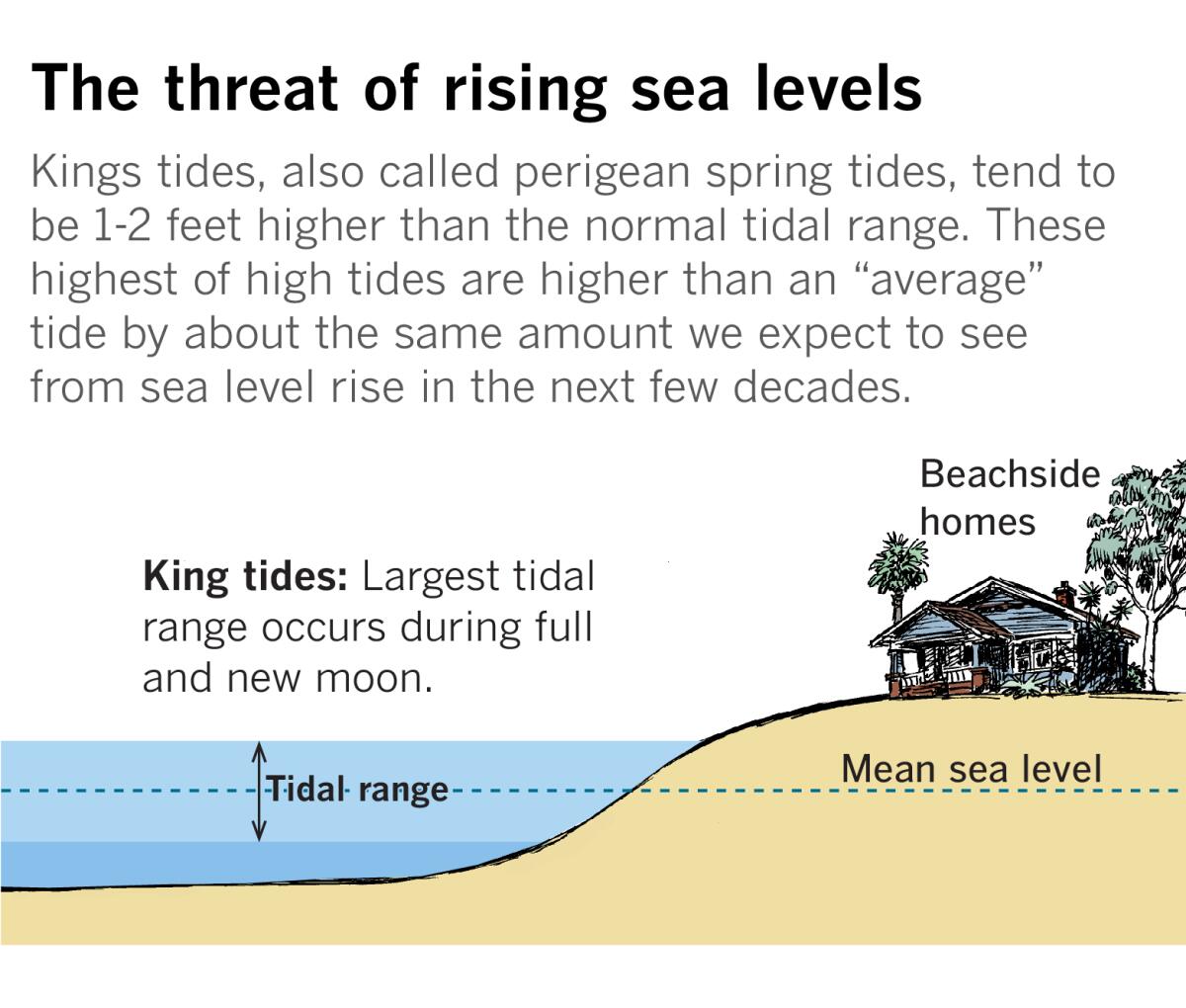

In California, most of the focus is on king tides associated with new moons during the winter because of the risk of coastal flooding. Often the flooding is minor “nuisance flooding” of low-lying areas, but it can be more serious.

King tides can give us a glimpse of what rising sea levels will look like. A king tide usually is 1 to 2 feet higher than the average high tide, but this may be exaggerated when combined with the almost inevitable winter storms and accompanying big surf along the California coast. In future decades, rising sea levels due to climate change are expected to result in average high tides that may be as high as king tides of today. King tides in future decades are then expected to be 1 to 2 feet higher than that, and they will also be combined with the effects of winter storms, pushing the high tides even higher.

As Californians face non-stop rain from an atmospheric river this week see how rainfall totals in your area compares to other regions and previous years.

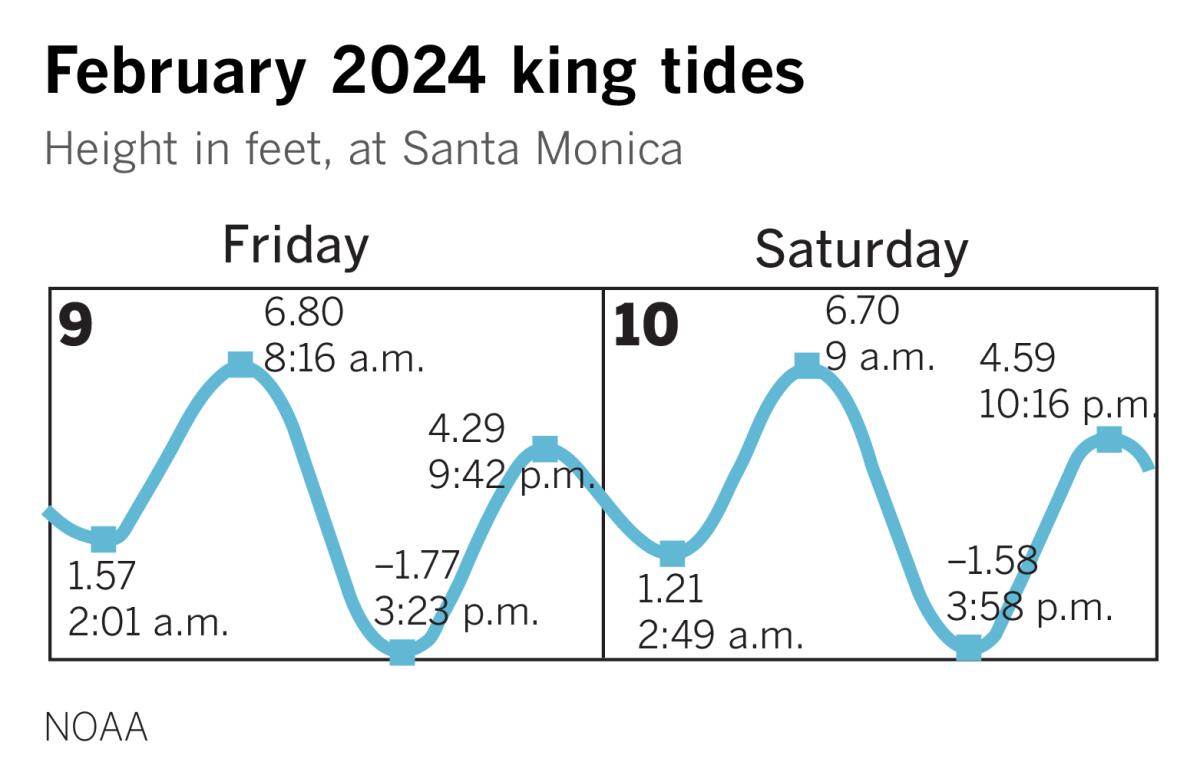

Southern California saw stormy seas combine with king tides on Jan. 11-12, causing flooding of low-lying coastal areas. New moons at perigee will occur again on Feb. 9, March 10 and April 8. The new moon will be the closest to Earth on March 10 and Southern California will be able to see a partial solar eclipse on April 8 as the new moon passes between the sun and Earth.

Coastal flooding can also occur with king tides during the summer and fall. There will be four full moons that are close to perigee in 2024: Aug. 19, Sept. 18, Oct. 17 and Nov. 15. The Hunter’s Moon on Oct. 17 will be the closest to Earth, resulting in a king high tide of 6.82 feet at 9:57 a.m. in Santa Monica, according to tide charts produced by NOAA.

The California King Tides Project is a partnership of government and community organizations that photographs these high tides and helps people visualize rising sea levels by observing the effects of the highest tides on California’s coast, beaches, beach access, infrastructure, habitat and estuaries today.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.