From a federal penitentiary in Virginia, Jose Landa-Rodriguez reconnected with an old friend in California.

“Long time no hear, you know?” he told Hugo Montes in Spanish in a recorded call.

Pleasantries gave way to business when Montes pitched Landa-Rodriguez on a deal.

“This is something that is going to interest you for the rest of your life,” he promised.

Both men were from Michoacán, a state in western Mexico where a drug cartel called La Familia was producing enormous amounts of methamphetamine.

Montes distributed the cartel’s product in Los Angeles. Landa-Rodriguez, nicknamed “Fox,” was a member of the Mexican Mafia, a syndicate of Latino gang members held in American prisons that “taxed” drug dealers but did not operate as wholesalers themselves.

The deal Montes wanted to make with Landa-Rodriguez was unprecedented.

La Familia wanted protection for its members in American prisons, a seat on the inmate councils that run day-to-day affairs on prison yards and help collecting debts and committing murders on U.S. streets. In exchange, the Mexican Mafia would get an endless supply of meth at a price low enough to corner the Southern California drug market.

The deal offered a different kind of benefit to the man who ultimately took charge of the negotiations: Ralph “Perico” Rocha.

A 20-year member of the Mexican Mafia, Rocha had the authority to represent his side of the table, and, unlike Landa-Rodriguez, he could negotiate with the cartel outside of prison.

Rocha was free because he was an informant for the U.S. government. Facing life in prison for extortion, he had made a deal to wear a wire and testify. In exchange, authorities reduced his sentence to time served and paid him nearly half a million in taxpayer dollars.

Flipping Rocha was supposed to have been an investigative coup for the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. But by the time Landa-Rodriguez spoke with Montes a year later in 2011, Rocha hadn’t delivered. His criminal associates had all been arrested by other law enforcement agencies that either didn’t need or didn’t want Rocha’s help.

And so it was a stroke of luck for Rocha — and the investigators counting on him — when he got wind of the would-be alliance with La Familia.

It was the kind of case that could make an agent’s career. What none of them knew was that their star informant was making tapes of his own, memorializing his dim view of how they did their jobs.

They played up the threat of the Mexican Mafia, Rocha said, both to scare the public into raising their budgets and to justify their plum assignments on gang task forces.

Rocha’s words jeopardized the case he helped build, none more so than the claim that his handlers, hoping to make a sensational case, took steps to keep the “marriage” between La Familia and the Mexican Mafia alive.

“They allow a lot of stuff to happen,” he mused in one tape, “and help create other stuff to make a certain type of bust.”

The chain of events that led Landa-Rodriguez to Montes — and eventually to Rocha — began years earlier, when Los Zetas, a cartel founded by deserters from an elite Mexican military unit, spilled out from their base in northeastern Mexico and overran Michoacán. Local traffickers rose up against Los Zetas, announcing their counteroffensive by rolling the severed heads of their enemies onto a nightclub floor.

Calling themselves La Familia, they had promised to retake “Michoacán for Michoacános.” But before long they had subjected the state — one of rugged beauty, known for producing limes, avocados and a diaspora of immigrants across the United States — to the same extortion and corruption practiced by Los Zetas.

By 2011, its leaders were concerned by a series of U.S. prosecutions called Project Delirium. Cartel figures were facing extradition to American prisons, the domain of the Mexican Mafia.

Connection between the Mexican Mafia and La Familia

La Familia, a cartel based in the western Mexican state of Michoacán, wanted the Mexican Mafia to protect its leaders in U.S. prisons. In exchange, they offered the Mexican Mafia a bottomless supply of methamphetamine. In the middle of the negotiations between the two groups was Ralph “Perico” Rocha, who was secretly an informant for the U.S. government.

Ralph Rocha, aka Perico

Government informant who led negotiations between the Mexican Mafia and La Familia cartel.

Hugo Montes

Los Angeles-based distributor for La Familia who proposed a deal between the cartel and the Mexican Mafia.

Jose Landa-Rodriguez, aka Fox

Mexican Mafia member whom Hugo Montes first approached about a deal with La Familia.

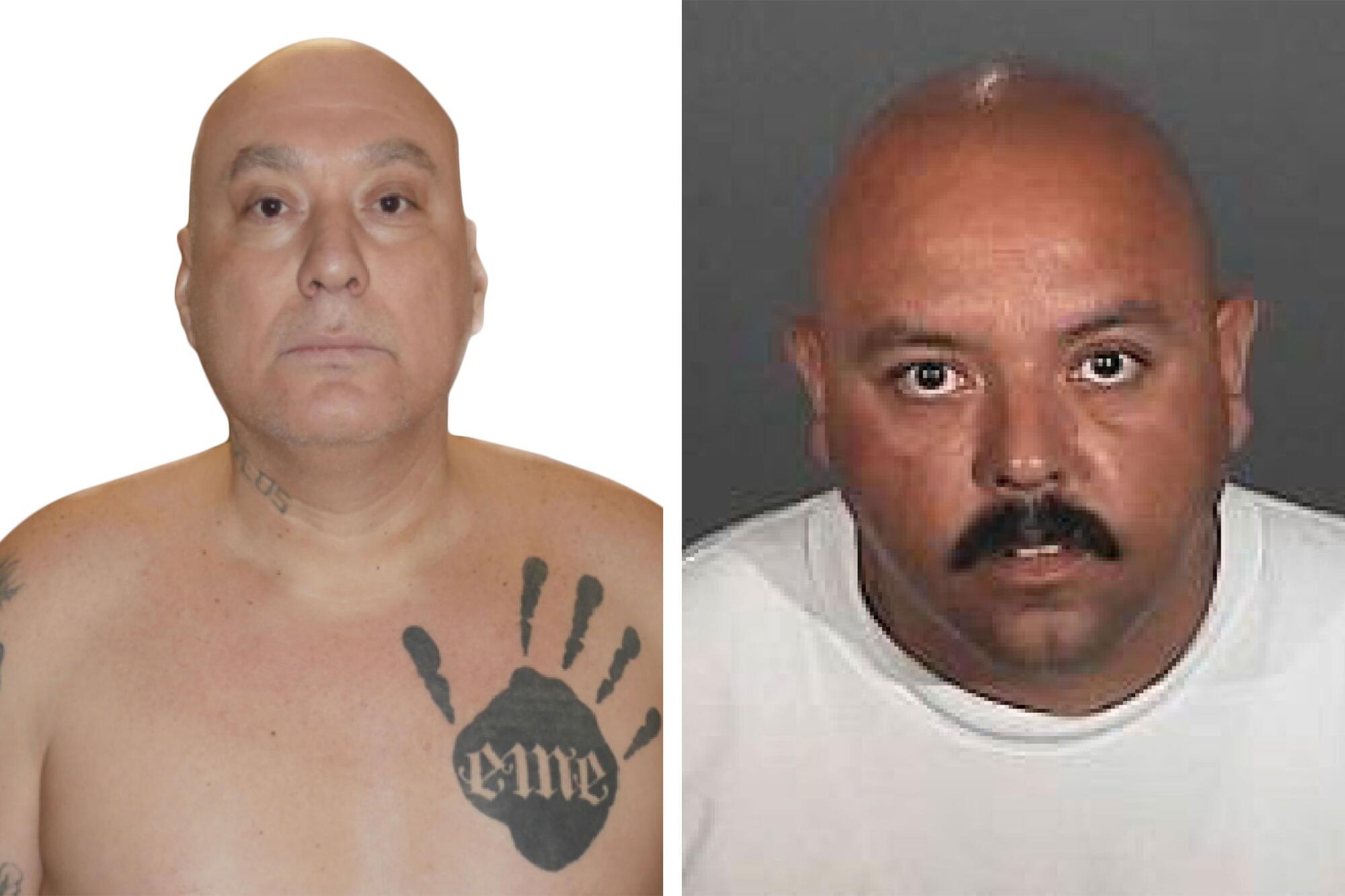

Michael Moreno, aka Mike Boo

Mexican Mafia member who introduced Ralph Rocha to Hugo Montes.

Fred Montoya, aka Fast Freddy

Mexican Mafia member who traveled to Mexico to meet with La Familia’s leaders.

Nazario Moreno Gonzalez, aka El Mas Loco

La Familia co-founder who met with Fred Montoya in Michoacan.

Efrain Rosales, aka Tucan

La Familia plaza boss who met with Ralph Rocha.

The potential deal between the two organizations was rooted in global criminal ambitions, but for the man with the connections to get it done, it was about a brother’s love.

Montes didn’t even expect to see the deal through himself. He was dying of cancer; doctors had been saying he had two weeks to live for the last two years, he told Landa-Rodriguez. All he wanted was protection for a brother who was serving life in the California prison system.

Landa-Rodriguez told Montes to contact an old cellmate, who passed off Montes to Rocha. In his secret tapes, Rocha said the Mexican Mafia couldn’t grasp the scope of what the cartel was proposing. Rocha said all his peers wanted was a few thousand dollars up front, blind to the potential of doing business with a cartel that shipped meth north by the ton.

“I’d apply it to a faucet,” Rocha said in his tapes. “They’d rather turn on the faucet full blast and get as much as they can out of it... Instead of just putting out an even flow and get it all, drink as much as you want, learn to shut it off.”

Rocha sat down with Montes and his brother Freddie, with whom he owned an auto repair business in the San Fernando Valley, and a plaza boss of La Familia, Efrain “Tucan” Rosales. The ATF provided the setting: an unmarked building in a San Dimas office park, bugged with hidden cameras and microphones.

Rosales proposed a “marriage” between the cartel and the Mexican Mafia, Rocha recalled afterward.

“I go, ‘Well, how about this? We got Surenos” — gang members with ties to Southern California and loyal to the Mexican Mafia — “from California to New York. To Maine to Miami, to South, North Dakota. So what do you want? You want to take over the United States?”

“Dude’s eyes got this big. Big as silver dollars.”

For Rocha, the strain of being an informant, surrounded by men who would kill him if they learned his secret, was “like vertigo.”

Twenty years in the Mexican Mafia had left him “numb” to death, he said. But once he started working for the government and “respecting things for being right,” he said, “You think, man, I got kids. I don’t want to die tomorrow.”

He started drinking heavily. At 2 a.m. one Wednesday morning, a California Highway Patrol officer found him passed out behind the wheel of his silver BMW 745Li, stalled on the 10 Freeway in Ontario.

His eyes were bloodshot and his speech slurred, the officer wrote in his report. Rocha said he “worked for the government and that was all he would say.”

He had been driving without a license, which had been revoked after he failed to make child support payments.

The arrest, a violation of his cooperation agreement, threw the case he was building into jeopardy. His handlers could have torn up his deal, shut down the investigation and sent Rocha before a judge to face a life sentence. Instead, they asked the CHP not to bring charges until Rocha’s undercover work was over.

Rocha complained in his tapes that his ATF handler, John Ciccone, made him dip into his savings to pay his child support, promising to “funnel it back to me slowly.”

“I can only work with the money they give me,” Rocha said. “Which ain’t much.”

Ciccone testified he paid Rocha $447,000. In an interview, Ciccone, now retired, said the sum included reimbursement for expenses as well as income for the 2½ years he worked undercover.

“We’re not allowing him to work a job, so we’ve got to compensate him for that,” he said.

The cartel wanted Rocha to finalize the deal with its bosses in Mexico, but ATF brass refused to approve the trip, he said in his tapes.

The agency was reeling from the so-called “Fast and Furious” scandal, in which weapons trafficked into Mexico with the ATF’s knowledge were used to kill a U.S. Border Patrol agent.

Rocha turned to Landa-Rodriguez’s old cellmate, Michael “Mike Boo” Moreno, and another carnal, Fred “Fast Freddy” Montoya, asking them to cut off the GPS monitors on their ankles and travel to Mexico. Once they returned, they’d surrender to serve time for violating their parole in the California prison system, where they could tell incarcerated Mexican Mafia members about the pact.

“I tell them it’s vital,” Rocha said. “Something so big, so important. We can’t write letters. We can’t talk on the phone. That’s been our Achilles heel from day one.”

But when Rocha showed up at Moreno’s house in Fresno, “Mike starts backing out.”

“This is what you became a carnal for,” Rocha said he told Moreno. “If [there’s] any moment in your life that you’ve got to give to the Eme, it’s right now.”

As he listened to Moreno’s excuses, Rocha said he thought to himself: “I’m glad I’m getting out of this s—.”

Montoya, meanwhile, was arrested for tampering with his GPS monitor before he could flee to Mexico. With Montoya serving time for the parole violation at San Quentin, Rocha said he told his handlers: “I need him out here to go with us. So you need to squash his violation or make it work so he gets out.”

Prison records show that Montoya, who could not be reached for comment, was discharged 21 days after being arrested.

Rocha’s handlers denied on the witness stand and in interviews that they lobbied anyone to release Montoya. Rocha told The Times he couldn’t recall the incident but suggested he wasn’t always truthful in his recordings. “I might have over-exaggerated things, thinking I might write something. A book. Make something sound good.”

Four days after getting out, Montoya called Rocha from Michoacán. In a call that Rocha taped for the ATF, Montoya said he’d met Nazario Moreno Gonzalez, the cartel’s messianic founder, whom the Mexican government had erroneously declared dead a year earlier after a three-day gun battle.

Nicknamed “El Más Loco,” the Craziest One, he distributed to his followers a self-published book that preached the importance of abstaining from drugs and being on time. “Convince yourself the world isn’t an amusement park,” one typical passage read, “but rather a work environment.”

Moreno Gonzalez had descended from a mountain hideout dressed in all white, according to Montoya. “He presented himself only to us, the Eme,” Rocha said in his tapes.

After Montoya returned from Mexico a wanted fugitive, Ciccone was “stressing the f— out,” Rocha said. He claimed Ciccone gave him ATF money to pay for Montoya’s stay at a La Puente hotel while Montoya hid from his parole agent.

“They know where he’s at,” Rocha said. “And they could arrest him at any time. But because of the intricacies and the complications with this case, they’re letting — he’s staying out.”

Rocha’s handlers told The Times they didn’t allow Montoya to elude his parole agent or fund his life on the run. Montoya was eventually arrested in Bell Gardens, four months after he traveled to Mexico, parole records show.

Along with protection behind bars, La Familia wanted to use the Mexican Mafia’s muscle to control Southern California’s drug market. In his tapes, Rocha said he summoned gang members “from Bakersfield [to] San Diego” to a meeting at a warehouse in the San Dimas office park. He told them to target “anybody and everybody” who wasn’t selling La Familia’s product.

“They’ll probably kill them or just rob them, depending on the individual, I guess,” he said.

Rocha’s handlers said the talk of hurting dealers was just that — talk. Had they known a violent act was going to occur, Ciccone said, they would have intervened.

Imprisoned on the other side of the country, Landa-Rodriguez was being updated on the negotiations between the Mexican Mafia and La Familia when Hugo Montes, trying to avoid mentioning Rocha by name, said he’d met with “El Cotorro.” The Parrot.

“Oh, no, no,” Landa-Rodriguez said.

There was a time when the idea that Rocha might be a snitch was unthinkable to his carnales. His penchant for violence was well-known. Even after he became an informant, agents in an unrelated case intercepted a call in which the daughter of a Mexican Mafia member said she narrowly avoided being lured to a meeting with him.

“I wasn’t going to come out of there,” she said, adding: “I know how Perico works. I know how he gets down. That motherf— is ruthless, beyond ruthless.”

But Landa-Rodriguez had grown suspicious. He told the Montes brothers to stay away from Rocha and put the cartel deal on hold.

After learning of the call, Rocha said in his tapes, he told his handlers to put Landa-Rodriguez in solitary confinement and take away his phone privileges so he couldn’t contact the Montes brothers.

Defense attorneys referenced in court an email in which a federal prisons official wrote: “After being called by the ATF last night, I set some things in motion to have Fox and his cellmate, Ray Lozano, placed in SHU,” a term for the prison’s lockdown unit.

Ciccone said Landa-Rodriguez was sent to solitary confinement for violating prison rules, not because Rocha told them to do it.

Spooked by Landa-Rodriguez’s warning, the Montes brothers changed their phone numbers and sent word they didn’t want to deal with Rocha. Ciccone said this posed a serious problem: The brothers were the conduit that passed cartel dollars to the Mexican Mafia to build support for the deal. After they went into hiding, Rocha was accused of pocketing the money. Ciccone said he worried Rocha could be killed.

The task force sent informants posing as gang members to the Montes brothers’ homes with a phone number for Rocha. Ciccone said he figured the house calls would “light a fire under them.”

The Montes brothers got back in touch with Rocha, who then arranged the sole drug deal of the investigation: a two-pound sale of methamphetamine.

The ruse had worked, but the rumors shadowing Rocha hadn’t gone away. Police in South Los Angeles arrested a gang member carrying a note smuggled out of prison.

“Perico de Norwalk is a rat,” it read. “Ya sabes he’s got to go.”

With Rocha on the hit list, the task force took its case to the grand jury. The city’s law enforcement brass called a news conference. Standing in front of a table arrayed with seized guns, Andre Birotte, then U.S. attorney in Los Angeles, declared to reporters: “This is the largest single crackdown of the Mexican Mafia since the ’90s.”

Some of the defendants in the indictment pleaded guilty. Five went to trial. Just before it began in 2019, their lawyers obtained Rocha’s personal recordings from his ex-girlfriend.

Pointing to Rocha’s sneering appraisals of the defendants, the attorneys asked the judge to throw out the case. How could they be guilty if the government’s own witness said they were too stupid, too incompetent, to have accomplished the conspiracy on their own?

Of Moreno, the Mexican Mafia member in Fresno, Rocha said: “I don’t think he really got it and understood the depth of what’s going on.”

The Montes brothers “just seem to be flunkies.”

Montoya was so high on meth, “he’s just agreeing with everything I say.”

But there was also what Rocha said about his handlers. They were liars, he claimed, spreading “straight bulls—” about the Mexican Mafia in books and television specials to scare the public into raising their agencies’ budgets.

Rocha said when he asked why they exaggerated the Mexican Mafia’s reach and sophistication, “their response was, ‘Job security. If we don’t make it out to be more than it is, there’s no reason for our position. We’ll be a regular patrol cop.’”

Steven Kays, a retired Los Angeles County Sheriff’s detective who oversaw Rocha’s undercover role, told The Times that his old informant was “just blowing smoke.”

“We’re all aware what the mafia does, the control they have,” Kays said. “I’ve worked gangs most of my career. God help us if they ever get their stuff together.”

In a 2019 memo to prosecutors, Kays wrote that Rocha was trying to make his tenure as an informant sound “as interesting and riveting as possible” in his tapes. Like Henry Hill, the inspiration for Ray Liotta’s character in the movie “Goodfellas,” Rocha had ambitions of seeing his story on the big screen, Kays wrote.

Prosecutors did not call Rocha as a witness during the trial. Ciccone said it was the plan all along to keep him and his “serious amount of baggage” off the witness stand and rely instead on the recordings he made for the ATF.

U.S. District Judge Christina Snyder refused to let the defense call Rocha to testify in their own case. The only evidence that mattered, she ruled, was what the defendants said themselves.

That they wanted to sell drugs was beyond dispute. But as an attorney for Montoya — who was on tape declaring, “I’m a mother—ing dope dealer!” — put it to the jury, the defendants could not have pulled off the deal had Rocha not nudged it along. “And Perico was a paid informant, an employee of our government,” said the lawyer, Carlos Iriarte, “being monitored, driven, by the agents.”

The end result of a case that consumed nine years and untold amounts of manpower and money — including the nearly half a million paid to Rocha — was mixed.

One Mexican Mafia member was convicted of buying two pounds of meth and sentenced to 20 years in prison, although he was acquitted of the overarching conspiracy. The jury could not reach a verdict for another defendant. The rest, including Montoya and Landa-Rodriguez, were acquitted.

Rocha’s handlers considered the case a success. “Disrupting the project in and of itself from ever materializing, people don’t know how impactful that was,” Ciccone said.

La Familia has since splintered into smaller bands of traffickers. Moreno Gonzalez was killed — this time for real — in 2014. A Drug Enforcement Administration agent testified in 2019 that Rosales, the plaza boss with whom Rocha met in 2011, remained at large.

Ciccone played down the impact of Rocha’s secret recordings on the case, saying they didn’t influence the decision not to use him as a witness. What Rocha said in the recordings — and the fact he made them at all — didn’t surprise the retired agent.

“This was his way of trying to cover himself,” Ciccone said, “so if he thought he’d get screwed by the cops at the end of the day, he’d lay us all out.”

In the end, Rocha got all he’d been promised: a life sentence reduced to time served, a new identity, a place in the federal witness protection program.

In a recent phone call facilitated by Ciccone, Rocha walked back much of what he said in the tapes. Some of it he’d exaggerated, with an eye toward one day writing a book. Some of it — like his comments about law enforcement using the Mexican Mafia to scare the public — he no longer believes.

It was hard to explain why he made the recordings at all, he said. He couldn’t tell anyone about his double life. Putting it on tape was “like talking to myself.”

He stopped when he came to respect his handlers, he said, who showed him a different way to live. Wherever he is now, Rocha said, he has learned to appreciate “the things I took for granted.”

“It’s nice to smell the air, see the clouds, feel the sun,” he said.

It is a long way from where he’d spent the first four decades of life — jails, prisons, the streets. What he called “the jungle.”

“I always knew in my gut, in my heart — when I was doing that shit, I knew it wasn’t right,” Rocha said. “But when you’re in the jungle with jaguars and monkeys, you’re going to eat the jaguars and the monkeys to survive.”

Second of three parts. Friday: Betrayal and a messy death.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.