A huge deposit of marine fossils found under San Pedro High School

Hidden beneath concrete at San Pedro High School, construction workers found a buried secret — thousands of marine fossils echoing Palos Verdes Peninsula’s ancient geological past.

Researchers uncovered two distinct sites on campus where new buildings were under construction: a bone bed dating back 8.7 million years in the Miocene era and a shell bed about 120,000 years old from the Pleistocene era.

With construction of the buildings now completed, scientists are focusing on learning what they can from the fossils that date back several million years.

“There’s never been this type of density of fossils ever found at a site like this before in California,” said Wayne Bischoff, the director of cultural resources at Envicom Corp., who managed the collection of the fossils that were excavated. “It’s the largest marine bone bed found in Los Angeles and Orange counties.”

Bischoff said the marine fossils align with what researchers already knew: that for most of Los Angeles’s geological history, the land has been underwater.

“We’re kind of like detectives,” said Richard Behl, a geologist at Long Beach State.

Behl is testing the chemical and mineral composition of the fossil blocks, hoping scientists can learn more about these prehistoric environments including the atmosphere and the conditions that enabled animal remains to fossilize. “We got to find clues and piece those clues together.”

The fossils dating to the Miocene were encased in a type of fossilized algae called diatomite. Behl said the diatomite tells him that the area was nutrient rich with algae that supported a complex ecosystem including dolphins, fish and whales that crowded the area for food. Alongside the marine animals, Bischoff said he was excited to find an entire shore ecology that included skulls of sandpipers and pieces of driftwood in the bone bed.

“Once we started realizing that we had a mix of shore material ... I started thinking that there may have been an extinct island off the coast,” Bischoff said.

Bischoff hypothesized that during the Miocene era, a heavy storm washed plant and animal debris down from a prehistoric island into a submarine canyon before mud sealed the organic materials into a layer of sediment. Tectonic activity and receding ocean waters revealed those fossils after millions of years.

“After their experience on this site, [scientists] have started looking for other extinct islands,” Bischoff said. “It looks like there was a lot of islands that would form and then dissipate in the Channel Island zone.”

On campus, the construction of new buildings has beencompleted and 80% of the fossil blocks found in 2022 have been passed on to research and educational institutions, Bischoff said. Those fossils are now split among the Los Angeles Unified School District, the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, Cal State Channel Islands and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

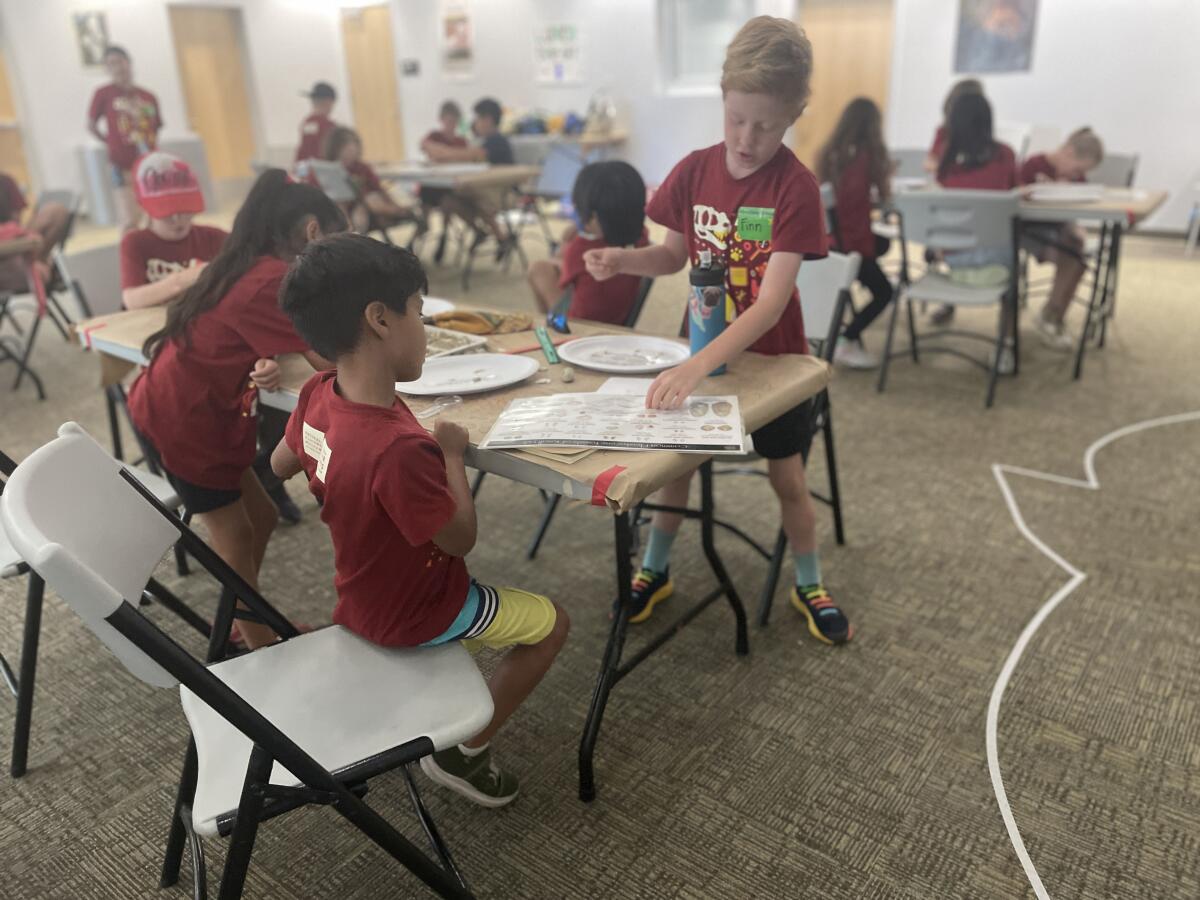

This summer, Austin Hendy, an assistant curator at the Natural History Museum who specializes in invertebrate paleontology, spent hours sifting and sorting through thousands of fossilized shells found in the shell bed.

The discovery has inspired at least one high school student to study the past as a way to understand the present.

“It was sort of like gold panning,” said Milad Esfahani, a San Pedro High student, who helped Hendy sort the fossils by size. “I would be tasked with looking for tiny, microscopic fossils like an 8th to 16th of an inch in size.”

It was the first time that Milad, a 17 year-old senior, had held a 125,000-year-old fossil and now he hopes to study marine paleontology at a university as he applies to colleges this fall.

The Natural History Museum hasn’t announced plans to display the fossils found under the school but already has a marine paleontology section on display called L.A. Underwater.

Hendy hopes that next summer he can work with another student to develop a display at San Pedro High School as part of the efforts to educate and engage the public on L.A.’s prehistoric past.

“Discovery can continue to happen — these blocks, they erode very slowly,” Hendy said of the fossil blocks extracted from the school. “We hope that the students and the public will be able to sort of clamber over these rocks in the years to come and be inspired by what they find.”

Although the work can be laborious and may seem pedantic to others, scientists such as Behl are drawn to this work because it reveals how our present is still being shaped by the Earth’s 4.54-billion-year history.

“It’s a real window into what the geography of the oceans and land were at the time when this occurred,” Behl said. “Even though that seems a long time ago, that has real impact upon everything we got today.”

In fact, many Angelenos rely on fossils to run everyday errands — they fuel our gas tanks.

“Those diatoms in that diatomite is what gives rise to the oil in Los Angeles” and the automobile and aeronautical industries, Hendy said. “The city owes its history to geology.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.