- Share via

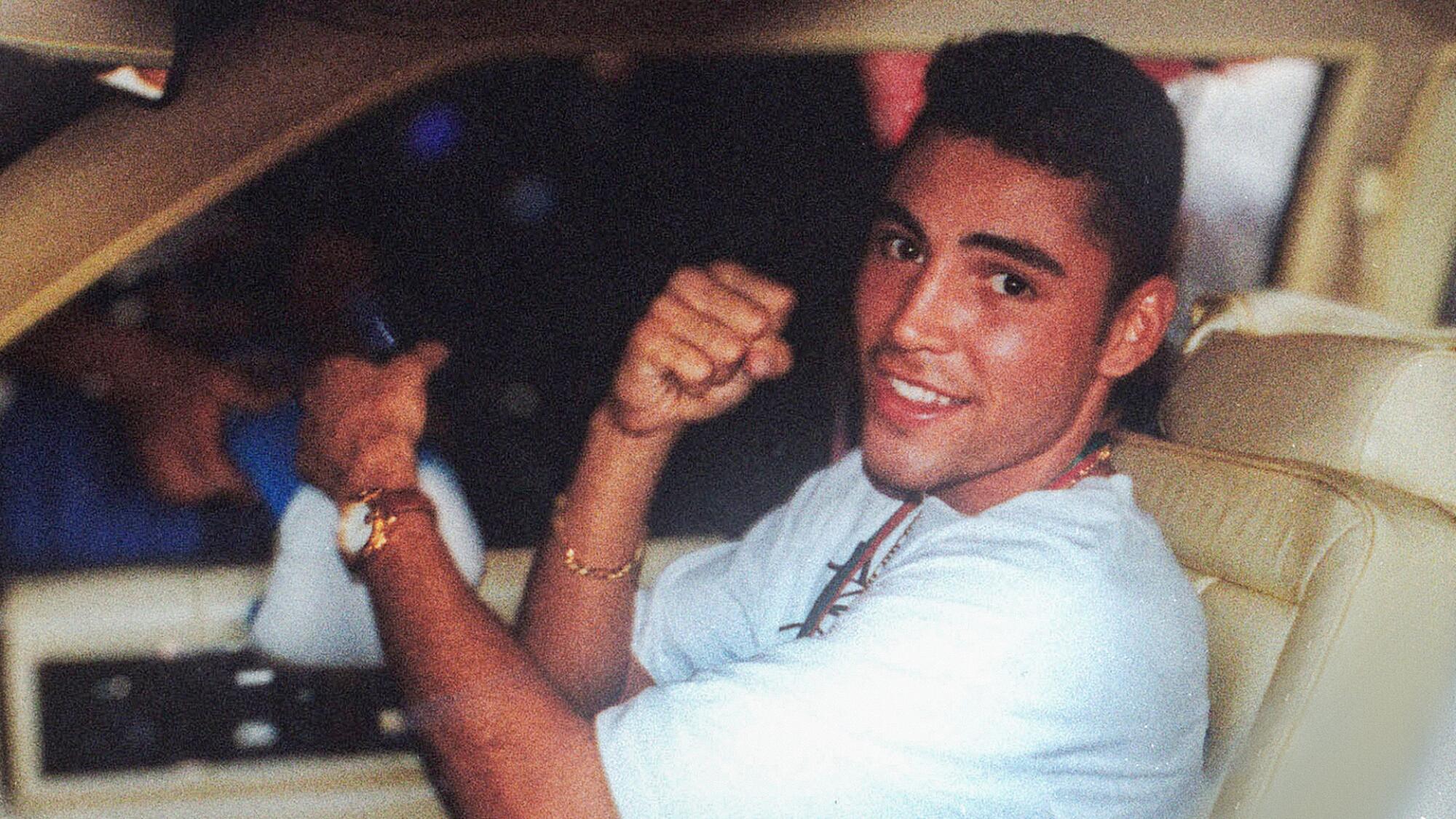

A couple of years ago, Oscar De la Hoya approached his father, Joel Sr., and told him: “I love you, dad.”

Joel Sr. started crying and told him he also loved him. These were words the former boxer would have appreciated hearing from his parents while growing up in East Los Angeles decades ago.

“When my mother was alive she never told me she loved me, or that she missed me. She never showed me any affection or love,” said De La Hoya in an interview with L.A. Times en Español.

The boxing legend took those emotions and channeled them into his relationship with his father. He began the “healing process” with his father by taking the first step in mending that connection and now realizes how important a relationship between parents and their children is.

“It’s part of our culture. My dad is macho and the strong man of the family, but why is that? I told him I loved him because he would never say that to me first,” De la Hoya said. “I know he loves me, but it’s nice to hear it every now and then.”

The communication within Latino families can be strained by strong cultural norms, including machismo, and this dynamic is reflected in the new HBO documentary “Golden Boy,” debuting Monday on the streaming service Max.

“Golden Boy,” directed by Ecuadorian filmmaker Fernando Villena (“Dear Rider” and “Any One of Us”), is divided into two parts and tackles the complicated relationship De la Hoya had with his parents, and the difficulties of dealing with newfound money and fame. The documentary also doesn’t shy away from the more controversial aspects of the boxer’s life, such as his infidelity, the breakdown of his marriage, and the embarrassing photos of him in women’s clothing that came out in 2007.

Even for those who have followed the story of the local boxing legend closely, there are new details that shine a light on his relationship with his mother. While the first episode looks at De la Hoya’s rise to superstardom, it also deals with the death of his mother right before he won a gold medal in the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona.

Cecilia De la Hoya died of breast cancer in October 1990 at 38 years old. Oscar was just 17.

The myth, perpetuated by De la Hoya himself, was that it was his mother’s dying wish that he bring the gold medal back to East L.A. with him, and the documentary examines how that relationship still resonates in De la Hoya’s life today.

“Humans are complicated, but we all want to be loved,” Villena said. “A lot of us have difficult relationships with our parents, especially in our formative years. The tragic thing about Oscar is that he was never able to repair that relationship with his mother because she died so young. There were a lot of things he left unsaid.”

This is Villena’s first foray into the world of boxing, and he quickly realized after talking with De la Hoya that to get at the truth, he needed to take the process slowly.

“It is not easy to unpack 40 years,” said Villena, who spent more than 50 hours over 30 different sessions speaking with De la Hoya.

The second part of the documentary deals with the emergence of De la Hoya’s business empire with Golden Boy Promotions and his attempts to break into the Latin music scene.

El film dirigido por el cineasta ecuatoriano Fernando Villena indaga también en el poco tiempo que tuvo para prepararse para el éxito, el dinero y la fama; además de sus adicciones, su matrimonio fallido y fotografías vergonzosas

Although he tried to establish a new life with his new wife, Millie Corretjer, his issues with drugs and alcohol plunged him into a disastrous moment in his career when photos surfaced of him dressed in women’s clothing while in the company of an exotic dancer, thus jeopardizing his business empire.

Villena mentioned that at the start of filming he didn’t know about the photos, but De la Hoya insisted that the truth about the incident be told. He asked HBO to track down Milana Dravnel, the photographer who took the controversial pics of De la Hoya, in Guatemala to get the complete story.

“It was another point in his life where he needed love, a shoulder to cry on and to be who he wanted to be,” said Villena.

Another key aspect of the second part of the documentary is how De la Hoya has interacted over the years with his three children, all from different mothers.

His three children — Atiana, Devon and Jacob — all share the difficulties of dealing with an absent father who would appear for short periods before disappearing again for years at a time. The more touching aspects of the film deal with the mental gymnastics the children have had to play in their lives and with their own relationship with their father. They seem to understand the difficulties their father has had with building relationships with them given his own problems with his parents.

“The film tries to create a different path for them to have a real relationship with each other and their family,” Villena said.

According to De la Hoya, he wanted to make this documentary to “be at peace with myself.” He wasn’t ready to tackle the difficult issues in his life, until now. He says years of therapy and the wisdom of age have helped him “heal his soul.”

“Oscar gave us permission to talk to whoever we wanted and gave them the freedom to say whatever they wanted to say,” said Villena, who insisted that the only direction he received from De la Hoya was to not sugarcoat the difficult moments.

Some of the strongest comments came from longtime friend and business partner Eric Gómez, who said that all you can do is “if he falls down 10 times, then you lift him up 10 times.”

According to Villena, working with De la Hoya marked a “homecoming of sorts” since he started working on the project while living in Boyle Heights.

“I want to explore more Latino stories, in all its complexities and all its humanity,” Villena said. “Each story shows another side to the experiences of Mexican Americans in the U.S. Each time these stories come to light, our experiences in this country come to light.”

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.