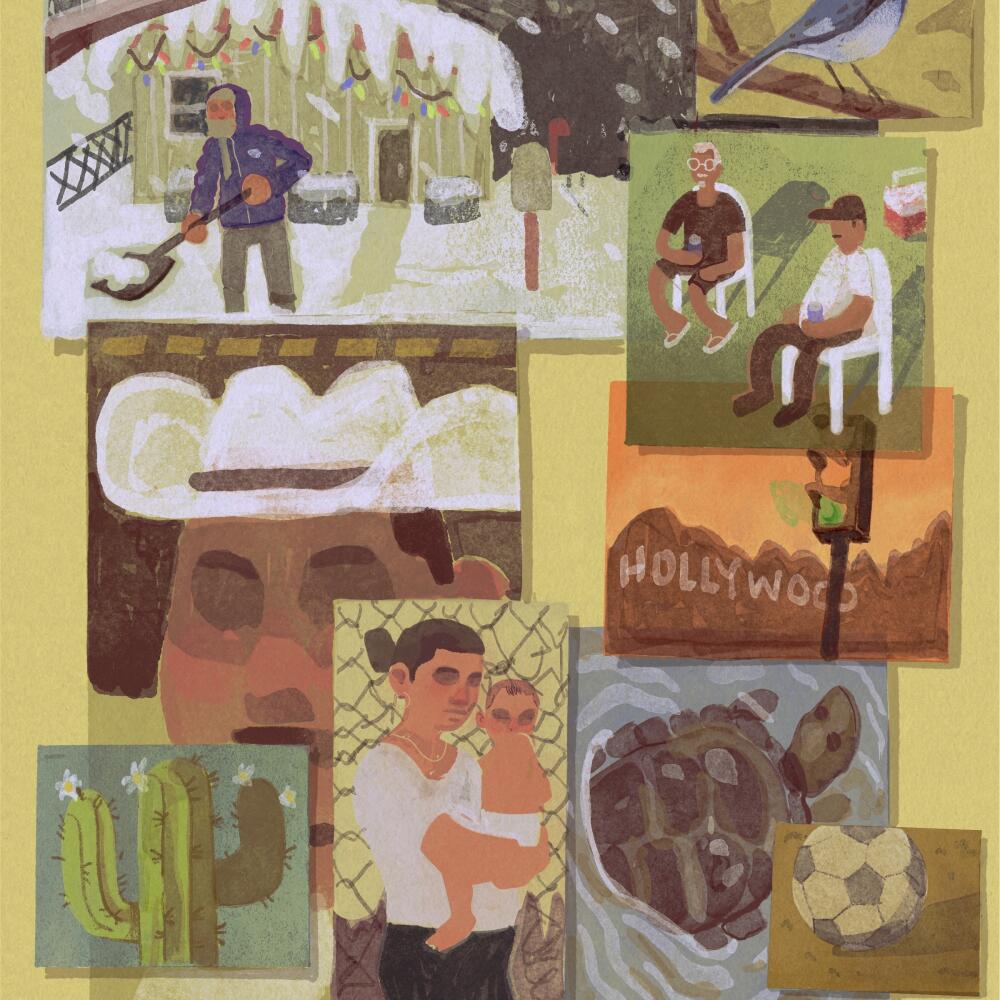

Our neighborhoods have shaped the people we are and are a core part of our identities. No matter how far we might go, we always carry a part of our hood with us.

De Los staffers are from a variety of places, and each of us has a relationship with the community we grew up in.

Mariana Trujillo Valdes

intern

San Gabriel Valley

There’s a lot to say about growing up in Los Angeles. It wasn’t until college that I understood how lucky I was to be constantly surrounded by individuals who looked like me. My parents moved to Los Angeles from Monterrey, Mexico, in 2001 and have been here ever since.

My dad’s mom’s family emigrated to Mexico from China. Growing up as a biracial child in Los Angeles taught me a lot. I’d have to juggle the idea of being “more Mexican” but looking “more Asian.” To this day I get asked a lot, “What are you?” I grew up in the San Gabriel Valley surrounded by Asian and Mexican cuisine.

‘What motivates us every day to write songs and music is the great pride of having Mexican blood in our veins.’

Since we don’t practice Chinese culture in my family, it was a way to learn about the cuisine, ethnicities and practices. This goes for my entire family, especially my mom, who didn’t grow up eating any Chinese food. Now dim sum Sunday is a family ritual. L.A. has taught me things about my Asian culture that I would not have learned in Mexico.

That being said, my Mexican heritage is strong in me: growing up eating my mother’s food, playing soccer since I was 4, enjoying carne asadas on the Fourth of July, tacos de canasta for breakfast, and visiting more places in Mexico than I have in the United States over my childhood. Being in L.A. encouraged me to learn about both of my cultures and realize that there is no one way to be Latina.

Kenya Romero

audience engagement fellow

East L.A.

My family and I lived in Boyle Heights until I was about 1 year old. My parents bought a house in City Terrace, a neighborhood in East L.A., and we’ve been here ever since. I honestly have not left L.A. for longer than two weeks, except for vacation. I grew up here, worked at a Panda Express in Boyle Heights as my first job and went to Cal State L.A., which is a 10-minute walk from my house. I feel grounded here. I have my community here. This is where I’ve found people and friends with similar backgrounds, heritage and culture. This is a community where I feel connected to my Mexican roots.

Diana Ramirez Santacruz

art director

Echo Park

To be specific, I grew up in Historic Filipinotown, which a lot of people don’t know about, but it’s practically down the street from Echo Park.

When I was younger, my mom and I would take the DASH to the park and then hit up the Echo Park Library. This was our daily routine during the summer, and it was the absolute best. We would grab raspados from the paletero man and wait for the turtles to peek their heads. I remember taking a turtle home with me and then having to come back with my dad to return it because we clearly could not keep it.

Members of the band, including lead singer JOP were detained by LAPD after their show at BMO Stadium on Sunday morning

I guess it’s really hard for me to say that I’m from this area without mentioning gentrification.

Growing up in this area felt ethereal. Have you seen the views? Anyone in Echo Park can agree that we have some of the best views of the city. After the park went through some remodeling, that’s when everything began to change. It was such a trip to see your neighbor (the pupusa lady) move out and be replaced with two white folks with a giant Great Dane.

It was then that I knew. A place that has been your home for years and yet never actually will be. So now I just take up space anywhere I go, and I encourage everyone to do the same.

Andrea Flores

reporter

Waukegan, Ill.

I have deep love and appreciation for where I come from, but it hasn’t always been easy. I would describe Waukegan as a midsize, working-class city with no more than 100,000 people, give or take. It’s right next to Lake Michigan and between Milwaukee and Chicago (right in between). It’s about 60% Latino, 20% Black and 20% white. There are a lot of Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Hondurans and Belizeans, so I never felt out of place growing up. I was always allowed to just be and exist as I am.

Waukegan is small enough that you can walk into the grocery store or gym and recognize someone immediately, whether you like them or not. Or sometimes you’ll see a familiar face and ask if they have any siblings because chances are you went to school with them.

Growing up, I used to get annoyed that I was from such a small town compared to other nearby cities like Chicago or Milwaukee, but I actually love that I’ve known people since kindergarten or high school. I have fond memories of bonfires, class recitals and other classroom shenanigans (school fights included).

For Chicanos in particular, the sweet treat has become a mascot. But what is it about the concha that has elicited such fanfare?

There’s something beautiful about watching other people grow up with you; it feels like they’re part of your family. Even now when I moved to L.A., I was able to find a place to stay because someone from Waukegan had a room open up. While the houses in Waukegan might be a little small or run-down and the streets have potholes galore, Waukegan is still the place I consider home.

Chelsea Hylton

reporter

Inglewood

Having grown up in Inglewood I am, proud to represent the community I’m from. My parents have lived in the same house for 29 years and have raised multiple children, held parties and made so many memories. I have never felt out of place in the neighborhood I grew up in. I grew up going to the Jamaican restaurant down the street from my house and buying groceries from the Latino-owned store. This was something very normal to me. Inglewood has been a predominantly Black and brown community for decades.

The neighborhood I used to ride my bike in as a little girl has seen me grow into the person I am now. When someone asks me where I’m from, my response is rarely just L.A. I am quick to say that I’m from Inglewood. My hood is a big part of me, and sometimes people are surprised when I say I’m from Inglewood, but I wouldn’t change it for anything.

Inglewood itself has seen a lot of changes. From being the home to the Lakers’ arena to having people displaced and now being a social hub in L.A. It has changed a lot, but it still remains my home. No matter how many billboards or venues get built in my community, the soul of the city has not changed.

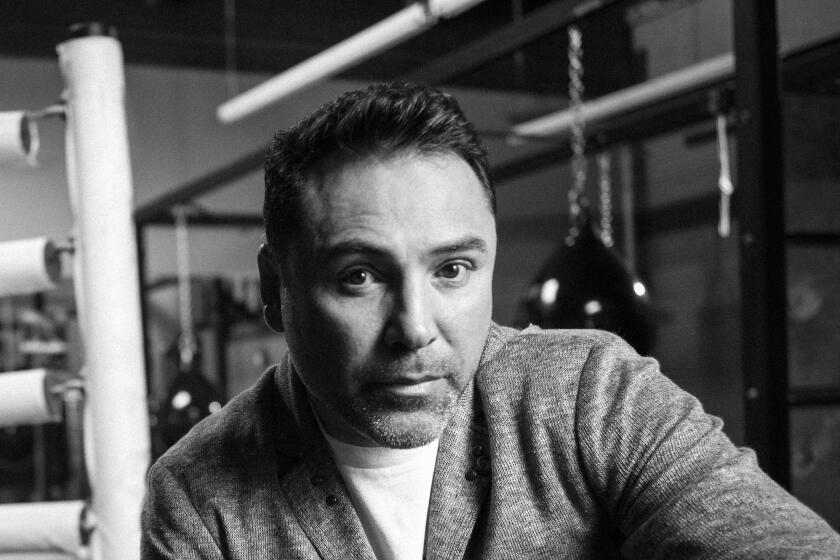

Angel Rodriguez

general manager

Houston

Los Angeles

Most people wouldn’t find many similarities between Houston and Los Angeles. Aside from the Texas versus California rivalry and more recently the animosity between Dodgers and Astros fans, there are the differences in climate and geography.

But as someone who has lived in Los Angeles for the better part of the last decade and who grew up in Houston, the two places feel very similar to me.

Both places are at the top of the list when it comes to diversity, with a rich tradition of Black, Latino and Asian communities forming the core of what makes these two cities tick.

The people of New Mexico were the first victims of the atomic bomb, the result of the Manhattan Project’s Trinity Test on July 16, 1945.

I had the luck to grow up in neighborhoods where Latino and Asian families would crowd the Black-owned BBQ place, where everyone ate Vietnamese and Cajun crawfish, and we all listened to Paul Wall and Mike Jones.

The presence of the oil industry and the Texas Medical Center meant that Houston was able to bring in families from all over the world to find work. Adding to the steady stream of immigration from Mexico and Central America was a large Vietnamese exile community that was drawn to the Texas coast. Over the last couple of decades, Houston has seen large communities of Nigerians and Indians add to the tapestry of the city.

If you grow up in Houston, you are used to being able to drive through all these different neighbors. You don’t realize how unique it is until you move away and find yourself looking around and not seeing all the different nationalities shopping at the same HEB.

It is why Los Angeles has a special place in my heart. When I arrived in 2015 it felt like home. It’s that feeling you sometimes get when you know you aren’t in your hometown but you still feel comfortable. It is why I think about my neighborhood in Houston when I bump into my Mexican and Filipino neighbors at the Salvadoran market on the corner.

Martina Ibáñez-Baldor

design director

Toronto

Wauwatosa, Wis.

I was born in Toronto and raised mostly in Wauwatosa, Wis. I loved Toronto and the mix of people, cultures and foods. I have fond memories of eating Jamaican patties and drinking mango shakes from the Guatemalan corner store. My classrooms and teachers were tolerant and accepting of the mix of immigrant families. My parents’ accents weren’t a shock to anyone.

When I moved to Wauwatosa, the experience was almost completely flipped. My family experienced countless microaggressions and straight-up racism. I grew up defensive, angry and ready to fight anyone who said anything racist to my parents or younger siblings. With no family in the States, I often felt lonely and isolated.

An exploration of marketing terms like ‘200%’ and how that’s shaped our identity.

My saving grace was friends. My best friends to this day are the friends I made in the first grade and later on in middle school. One of them had Mexican heritage and her mom became an ally to my parents (shout out Mrs. Hermsen). My friends and their parents were compassionate, understanding and caring. I wouldn’t have survived without them.

They taught me about American (and Wisconsin) traditions like Thanksgiving and turkey, St. Nick and early Christmas stocking, Memorial Day and lake houses. In high school, they taught me about homecoming, the parade, the bonfire and the football game. I sat my parents down to a PowerPoint presentation explaining the whole ordeal (and why I needed a new dress for the occasion). My parents complied with everything because they wanted me to fit in and be happy.

I often think about how my mother came to this country with no friends or family and how she managed to survive. I think she would say the same thing — her friends. She made friends through an Argentinian expat society, through her work and school. Her friends helped her through hard times and celebrated her happy times. That’s how she built her community, as did I. When we had no family to lean on, we leaned on our friends.

Christian Orozco

assistant editor

La Habra

Growing up in La Habra didn’t always invoke neighborhood pride, and I always envied the cities that did. Being from north Orange County, it always felt like our neighbors to the west in L.A. County were always having a party. I spent most of my life dreaming of getting away from La Habra.

Now I realize that what makes me love my city isn’t the politics or social activity, but the people and places that made me who I am. Whenever I’m asked, “What’s there to do in La Habra?” I still jokingly answer: “Leave.” But there is some truth to the answer.

The two people who made growing up in that city great were my parents, and they were always looking for things for us to do in surrounding cities. We were frequent attendees of the Santa Fe Springs Swap Meet. We didn’t have a mall in La Habra, but the Brea, Puente Hills and Whittwood malls were all within a 15-minute drive.

La Habra doesn’t have a freeway, which used to be an inconvenience as a commuter student in my college days, but it is now one of the more refreshing aspects of the city. I still go back and forth on my feelings about La Habra, but it will always be home.

Crystal Villarreal

assistant editor

Riverdale, Ga.

I didn’t realize how lucky I was to grow up in Riverdale, Ga., until I left. I’m Black and Mexican, but I grew up in a predominantly Black city. Riverdale is on the south side of Atlanta, and like the south side of any city,there was crime and people struggling to make ends meet. But Riverdale was so much more than that.

A new documentary on Oscar De la Hoya takes a look at his triumphs and demons and the sometimes difficult relationships in Latino families.

All I could think about growing up was surviving and making it from one day to the next. A lot of our community was like that. We realized that we all had hardships, so we were always helping each other out and supporting each other. I knew if I needed anything, someone in my community would come to my help. Whether it was SAT tutoring, a ride home because I missed the bus or even a few extra dollars so I could go on a class field trip, my community always showed up and provided for me.

I relied on neighbors and close friends, and that’s how we were all able to get to the next day. The friends I made in high school are still my best friends to this day. The rapper T.I. and Ciara both went to my high school. Atlanta was fairly small during this time, so everybody knew everybody. It was great seeing so many people from my hood succeed in life — Ludacris, Jermaine Dupri, Monica — watching them fight to get out and achieve their dreams gave me this special belief in myself that I could do whatever I wanted in life even if I was just some Black girl from the south side.

There are some things I really miss, like skate nights at Sparkle and Skate Town, the candy lady and the best hot wings ever. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that my hood has stuck with me. Whenever I have any success or any milestone in my career, it’s the folks from my hood who show up and show out for me.

Alejandra Molina

reporter

El Monte

Coming of age in El Monte, I often think back to the Starlite Swap Meet, a former drive-in along Rosemead Boulevard that we would frequent as a family on the weekends.

It’s where I felt we were treated like VIPs.

My parents knew the man working at the main entrance. They were from the same town in Guanajuato, Mexico. I don’t remember his actual name, but everyone called him “El Davis.” My mom and dad would strike up a conversation with him, and several times he would just let us in for free.

It’s also where I would see my parents in all their bargaining glory. I remember my dad chatting up Asian vendors trying to cut off a few cents from a packet of white cotton socks. Every little cent counts!

The swap meet was massive, with rows and rows of vendors selling purses, shoes, strollers, tacos and burgers. Sometimes, I’d even see my middle school peers working the stands to make a few bucks.

‘People are just not feeling accepted within that box that the Catholic Church is desperately holding on to.’

It always felt like you were in a community.

I’m not sure if the swap meet reopened after the pandemic, but I hope these kinds of gathering spaces can be preserved. Growing up across Southern California, shopping districts like “La Pacific” in Huntington Park and the Valley Indoor Swap Meet in Pomona were spaces where immigrant families like my own would shop for back-to-school clothing, for piñatas and party supplies to celebrate birthdays, or to simply say hello to a family friend.

Jessica Perez

community editor

Boyle Heights

I’ve always called Boyle Heights home. It wasn’t my place of birth or where I live now, but it’s where I was raised and where I learned the meaning of community. There, I navigated buses to my summer high school jobs at Baskin-Robbins and the old Sears building. It’s where I had my first kiss and where I brought home my first daughter.

Boyle Heights was not the safest place to live in the ’80s and ’90s, so my parents sent us to schools outside our neighborhood. I spent a lot of time trying to assimilate, hiding my undocumented status, embarrassed of speaking Spanish and ashamed of being from the neighborhood where all the gang movies were filmed. Every day, I came back home from the more affluent San Fernando Valley, and for a while, I thought I wanted to escape my community. But who would tell the many inspiring stories of passion and hard work that I saw in my neighbors?

The way Roosevelt High School educators were teaching students about their rights and what it meant to exercise their civic duty at protests; how first-time entrepreneurs were opening up businesses along 1st Street as a way to resist gentrification in their communities; or about the immigrant mothers in Ramona Gardens who became promotoras, informing residents about healthcare, education and resources.

I began documenting the people around me, telling the stories of those who were often not heard. Then I mentored youth at Boyle Heights Beat, a bilingual community newspaper and youth journalism program. This was my way of giving back to a community that gave me so much. There, I didn’t have to assimilate or hide. I could just be me, be proud of who I was and where I came from.

Raul Roa

photo editor

South Los Angeles

Growing up in South-Central Los Angeles in the late ’60s and ’70s, the neighborhood did not have too many Latinos. There were some neighbors a few doors down who were Latino, but they were not the kindest people. Other neighbors on either side and up and down West 39th Place (near Budlong), were African American, for the most part. My immediate neighbor, Henry Duvall, was a World War II veteran who worked in the juvenile hall system. He was a kind, 6-foot-2 African American.

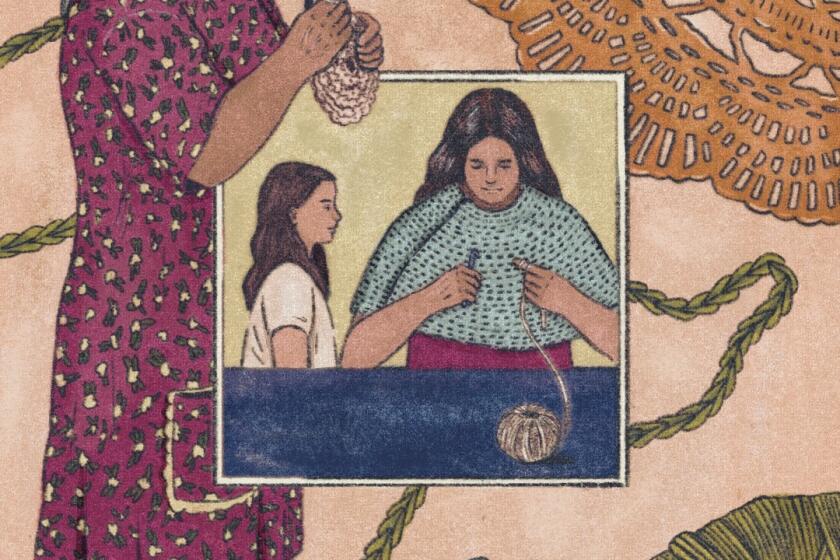

With every stitch, every loop and every turn of the hook, I carry the legacy of my great-grandmother and my mom, as well as the cultural history of Mexico.

When I was young, around age 9 or 10, Henry took me and my two sisters under his wing and taught us a lot about the arts, reading and sports. My parents were good parents. They worked hard to keep food on the table, a roof over our heads and in private school, but they did not have much time or money for anything else. Henry knew the struggle my parents were going through, so he would take us to the park sometimes or other interesting places.

Since we lived only three blocks from the L.A. County museums and USC, he would walk us over and introduce us to other aspects of life that helped shape who we are today. Henry taught me how to throw a football, a baseball and the shot put. He always said “practice makes perfect,” and I believed him and still do. Seeing my parents work hard and Henry’s life lessons influenced me in my work ethic and treatment of others.

Fidel Martinez

editorial director

Rio Grande Valley, Texas

Growing up, I couldn’t wait to leave the Rio Grande Valley. I had this desire to learn what existed beyond the border checkpoint 70 miles north, beyond the Texas state line, that motivated me to skip a year of high school. Such was my desire to get out that one of the first colleges I applied to was Bowdoin in Brunswick, Maine, because it was more than 2,300 miles from Hidalgo, Texas.

It’s been 21 years since I left for college, and in that time I’ve seen the world — well, the United States and many parts of Mexico, though I did go to France one summer. Eventually, I found myself in Los Angeles, a city I have no intention of leaving. But if I do, if this whole journalism thing doesn’t pan out, it would be to go back to the RGV (obligatory: Puro 956, cuh!), to the borderlands where the Mexican meets the American.

I would return to where I can see my nephews live out their soccer fantasies under the Friday night lights of the McAllen Sports Park, an activity that has become a ritual for my entire immediate family. I would go back and wait in line with my dad early Sunday mornings to get barbacoa at Kiko’s in Las Milpas or pick up my mom after her shift at the PSJA North High School cafeteria.

This, in my mind, would be a pretty solid way to live.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.