21 new and classic books to keep you in touch with the natural world

If you notice anything,

it leads you to notice

more

and more.

— Mary Oliver, “The Moths”

Like many who grew up on the West Coast, I discovered that hikes in the woods in the shadows of mountains were when my chest could crack open and the hamster wheel of thoughts could rest. Many of us are finding comfort now in remembering the enveloping smell of warm pine on a sunny day or the sight of ocotillo in bloom after a desert rain.

In the time of coronavirus, we circle our blocks cautiously, while trails and beaches are closed for our protection. Nature flourishes in our absence, awaiting our return. In these 21 nonfiction books, both recent and classic, writers illuminate a natural world that reflects back to us the wonders of this troubled planet. The list is far from complete; consider it a starting point toward virtual encounters with nature — until you meet again.

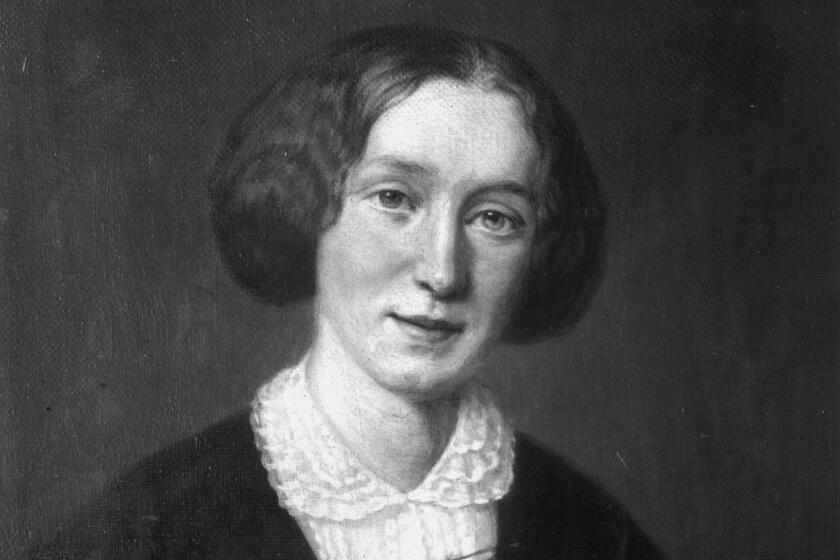

Writing Wild

By Kathryn Aalto

Aalto profiles 25 female writers, activists, naturalists and mavericks who advocate for the natural world. Each profile is a biography but also an extensive reading list of books on or about or even tangentially related to the subject. It’s a fantastic resource for readers looking to grow their TBR piles.

The Hidden World of the Fox

By Adele Brand

The last wolf was killed in Britain 800 years ago. The red fox, on the other hand, is a frequent sight in the English countryside. In towns and cities, foxes live side by side with Britons and are as ubiquitous as raccoons are in America. Brand has studied foxes on four different continents for 20 years. She shares her observations and the history of an animal remarkably adaptable to human environments.

The Colors of Nature

By Alison Hawthorne Deming and Lauret Savoy

Thirty writers contributed essays to this anthology, offering ways of thinking and writing about nature that diverge from the largely white field of environmental literature. They map the intersections of environmental awareness, ethnicity and varieties of cultural inheritance. The result is a marvelous, textured demonstration of the immense benefits of diversity in meeting great challenges.Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

By Annie Dillard

Published in 1974, Dillard’s diary of a year spent by Tinker Creek, which runs near Roanoke, Va., in the Blue Ridge Mountains, combines close observation with a philosophical inquiry about theodicy. Nature evokes questions about faith and the role that a deity may or may not play in what she sees. She has long argued that the book is a work of theology, rather than a nature journal. Why not both?The Solace of Open Spaces

By Gretel Ehrlich

Ehrlich has written several books on landscapes ranging from the Southwestern U.S. desert to Japan after the 2011 tsunami to the ice fields of Greenland. This 1995 book covers her time in Wyoming, which she lays bare in 12 essays that could each stand alone. Moving there after a tragic loss, she found a landscape of “absolute indifference” that nonetheless inspired achingly beautiful prose about love and grief.

Eight great very long books you finally have time to read if you’re under coronavirus self-quarantine or just embracing social distancing.

The Falcon Thief

By Joshua Hammer

In 2010, customs agents in Britain apprehended Jeffrey Lendrum, who was smuggling 14 peregrine falcon eggs beneath his clothes. Hammer’s investigation of Lendrum’s theft of the eggs from a cliffside and the underground market for rare raptors is thrilling. Lendrum’s customers turn out to be powerful, wealthy and ruthless in their demand for endangered birds.Braiding Sweetgrass

By Robin Wall Kimmerer

Kimmerer — a biologist, professor and member of the Potawatomi Nation — examines the reciprocity in the relationships between humans and the environment. The structure of the book resembles a braid, twisting together the three strands she describes as “indigenous ways of knowing, scientific knowledge and the story of an Anishinabekwe scientist trying to bring them together in service to what matters most.”

The Outrun

By Amy Liptrot

Liptrot grew up on a remote island in the Orkneys, an archipelago north of Scotland. She fled for London and city life as a young adult, but when a series of bad experiences and alcohol dependency began to take their toll, Liptrot came home to self-isolate, stop drinking and heal. That story of sobriety is woven in with the natural history of these remote, alluring islands.

The Home Place

By J. Drew Lanham

Lanham has been recognized for his scholarship and essays on birding and nature, but as a black man he is also aware that being able to walk alone in the wilderness is a privilege. In this memoir of a South Carolina childhood, he recounts his family’s relationship to the land, his evolution as a chronicler of the beauty of the state’s forests and farmlands and the dangers lurking in the woods of the Jim Crow-era South.

Horizon

By Barry Lopez

The veteran nature writer’s latest book provides a cartography of his life story, focusing on six geographical areas: the Oregon coast, the Canadian Arctic, the Galápagos Islands, Tasmania, East Africa and Antarctica. He is a terrific guide to Earth’s wonders, but he’s equally effective at calling readers’ attention to the environmental disaster that will overwhelm us unless we act.

My Penguin Year

By Lindsay McCrae

For 337 consecutive days, cameraman Lindsay McCrae made his home among 11,000 emperor penguins. In Antarctica, he watches as the colony experiences birth, death and everything in between. Annotating his photos, he writes of how penguins and humans alike adjust to an environment where temperatures can reach 60 degrees below zero. Filled with color photographs, this is a treasure.

Assembling California

By John McPhee

Now 89, McPhee is often regarded as one of the first practitioners of creative nonfiction, including his many books on the natural world. Here he writes at length on the geology of California, narrating the rise of the science of plate tectonics alongside. He mines stories drawn from the history of the Gold Rush and the development of the agricultural valleys that feed much of the United States.

Landmarks

By Robert MacFarlane

One of the U.K.’s premier nature writers turns his attention to the unique ways the wilderness has been marked by language. He intersperses glossaries of regional terms for natural phenomena (twindle, swelk, amod) with essays on the various biomes and geological formations of the British Isles. The result feels like an immersion course in the language of nature.

Why Fish Don’t Exist

By Lulu Miller

Taxonomist David Starr Jordan, born in the 1850s, documented new species of fish and contributed enormously to ichthyology. What made his story remarkable was the number of times he had to reconstruct his research (sometimes from scratch) after disasters destroyed his data. Lulu Miller draws a heartening lesson — that chaos, which comes for us all, can be defeated by sheer human stubbornness.

Animals Strike Curious Poses

By Elena Passarello

In 17 essays, Passarello investigates animals that played their part in history. The playful title, taken from a Prince lyric, is matched by the wit and erudition in the essays. Among her subjects are Mozart’s starling, who sang one of his early works back to him; Dürer’s rhinoceros, immortalized in a woodcut; and Darwin’s lovesick tortoise. Each essay is a bonbon as delicious as any Instagram animal pic.

11 authors, from Laila Lalami to Jonathan Lethem, on the books they might finally read in quarantine

Including Lawrence Block, E.M. Forster, Dostoyevsky and lots of “Middlemarch”

Ecology of a Cracker Childhood

By Janisse Ray

Growing up in rural poverty in southern Georgia, Ray escaped the disorder around her by seeking solace in nature. This seeded in her an awareness of the environmental threats that surround the ecosystem of longleaf pines, which once covered much of the South but are now reduced to isolated stands. Her impassioned memoir moves between the painfully personal and the long reach of history.

Trace

By Lauret Savoy

Lauret Savoy studies the impact of human migration on the land. Expanding on the idea that sand and stone are part of Earth’s memory, she asks how human memories of land are recorded or erased. From these questions emerges an understanding of how claims are evaluated and stories told based on the race or ethnicity of those affected. A lyrical and expansive work.

The Ravenmaster

By Christopher Skaife

A consistent treat for visitors to the Tower of London is its famous resident ravens, and Skaife is the Ravenmaster, given the task of caring for the birds. Legends hold that if the birds ever leave the Tower, the structure will crumble. Skaife’s sense of humor inflects the writing. Combining his firsthand observations with historical accounts of other corvidae, Skaife lets readers in on the ravens’ conspiracies.

The Book of Eels

By Patrik Svensson

Eels have fascinated and repelled humans for millennia — and inspired those feelings in Svensson since he was a boy eel-fishing with his father. It turns out they were also very mysterious: For the longest time, no one knew where they came from or how they reproduced. Drawing from literature, science and his own studies, Svensson inspires readers to see eels in a whole new way.

An Unspoken Hunger

By Terry Tempest Williams

Williams has published multiple books on how our belief systems influence our attitudes. “An Unspoken Hunger” collects early essays on her work in the field, which took her from Great Salt Lake to the African savannah and beyond. She’s particularly sharp in exposing our domination of the wild as a displaced desire to control the wild within ourselves.

Tarka the Otter

By Henry Williamson

Next month, New York Review Books will reissue Williamson’s 1927 novel about the otters of North Devon. If that sounds cute, it’s not: Writing from the perspective of Tarka as he roams the countryside, Williamson emphasizes the brutality and competitiveness of the species, as well as the bloodlust of humans who hunt them because they envy their salmon.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.