Woody Allen’s publisher can’t be canceled

They knew it was coming. Weeks before Vanity Fair’s exposé was published, Skyhorse Publishing was prepared for the worst. And they got it. “Skyhorse Publishing’s House of Horrors,” blared the Sept. 17 headline. In addition to questioning the omnibus book publisher’s editorial decisions and integrity, the epic takedown by Keziah Weir alleges a toxic work environment, complete with massive workloads, union busting, inappropriate relationships and instances of harassment. (“The article is incorrect,” writes Skyhorse president and publisher Tony Lyons in an email. “There is no one working at Skyhorse who has been accused of harassment.”)

The real driving force of the story, and the obvious occasion for its publication, was the lineup Skyhorse has chosen to publish, embracing an “all-sides” approach even on issues — the coronavirus, for example — where the truth very heavily favors just one. Skyhorse’s practices raise all manner of questions that also apply to the industry as a whole: What are a publishing house’s core responsibilities? How much does objective truth matter? What, and where, are the accepted standards — if they exist at all?

“It’s dangerous to think about publishing as a means of disseminating truth to the masses,” Lyons writes in an email. “We publish arguments. Readers should decide what they believe.”

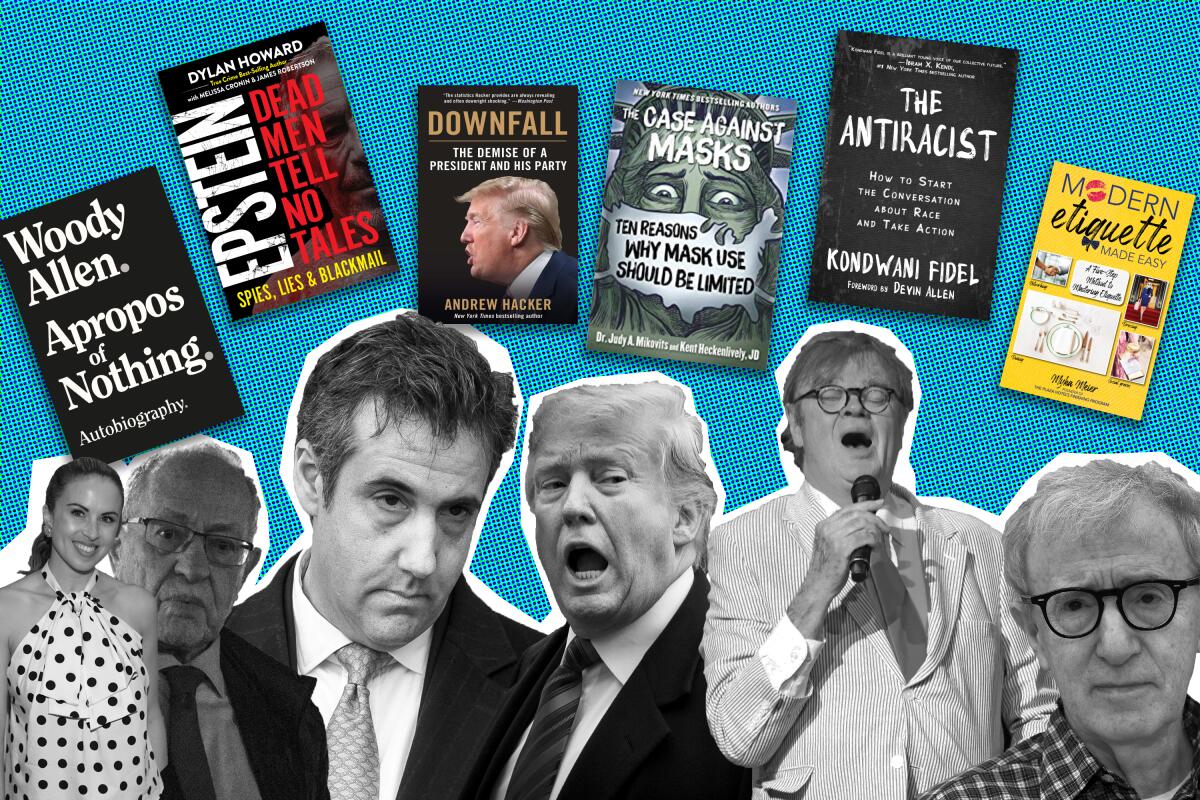

An independent publisher with 20 imprints and 750 titles planned over the next year on everything from sports to politics to country living, Skyhorse was launched in 2006 as a purveyor of crunchy hunting-and-fishing-type books. More recently, it has become better known as a publisher of last resort. Among its recent and upcoming titles: “Disloyal,” a memoir from former Trump fixer Michael Cohen; “Plague of Corruption,” co-authored by discredited COVID conspiracy slinger Judy Mikovits; and “The Lake Wobegon Virus,” a novel by Garrison Keillor, fired by Minnesota Public Radio amid allegations of inappropriate behavior.

And Woody Allen.

Perhaps no other medium has better helped us process 2020. Our fall books special brings you the books and authors who’ve helped make sense of it.

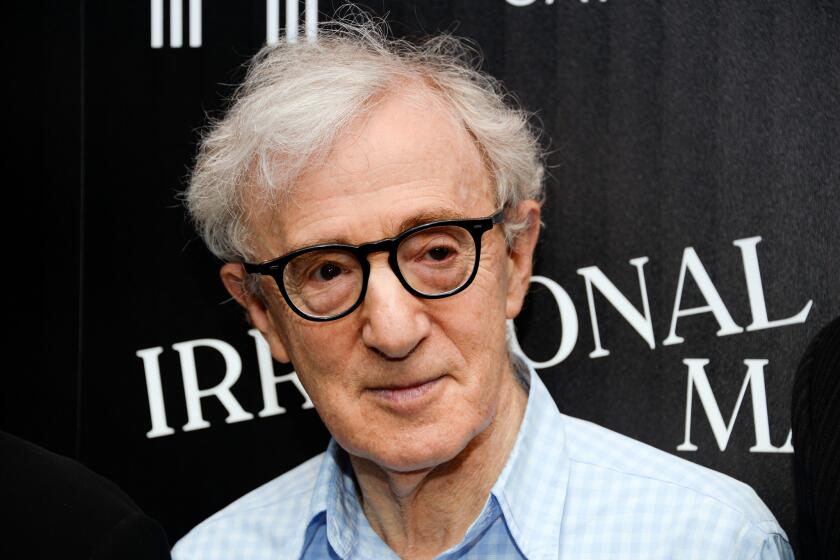

If you want to understand the cultural forces that led to a glossy magazine’s demolition of the publisher of “12 Lessons in Business Leadership” and “The Super Cool Science of Harry Potter,” it helps to go back to March, when Hachette Book Group, a mainstream publishing conglomerate, announced Allen’s memoir, “Apropos of Nothing.” Allen had drawn intense criticism (but continued to make movies) ever since his daughter, Dylan, accused him of sexually molesting her as a child (Allen has denied the charges). Four of the five major publishing houses steered clear of his latest book before Hachette pulled the trigger.

The outrage was broad and deep; dozens of employees of Hachette imprints walked out in protest. But the final straw was Ronan Farrow, Dylan’s brother. His New Yorker exposé on Harvey Weinstein, combined with his fame, made him the highest-profile journalist of the #MeToo movement. He threatened to sever ties with Hachette, which had published Farrow’s follow-up book, “Catch and Kill.” And so there was only one choice: cancel the director’s memoir.

Except it wasn’t canceled, because no book is really canceled as long as Skyhorse is around.

“The Woody Allen book fit in well with our philosophy of taking a strong stance against cancel culture,” Lyons told me by phone before the Vanity Fair piece came out. (He replied only by email afterward.) “Woody Allen has had an incredible career as a filmmaker, an actor and a comedian. He plays an important part in American culture and he has a fascinating life story.”

There it is, the big double-C: cancel culture, a term so loaded that even uttering it means taking a side. It’s meant to encompass everything from pulling reruns of “The Cosby Show” after its creator’s conviction for indecent assault to pulling advertising from Tucker Carlson, who remains very much un-canceled. Both the left and the right engage in cancel culture, but the right, which likes a good boycott as much as anyone (witness the furor over Netflix’s “Cuties”), is more likely to label it a purely liberal sin.

Woody Allen’s memoir “Apropos of Nothing” was released Monday by Arcade Publishing. The book was dropped earlier this month by Hachette after much criticism.

Yet the notion of cancellation is not new — least of all in publishing, whose contracts often include clauses regulating an author’s public behavior. Nor is Skyhorse the first house to specialize in scooping up the dregs. In 2006, O.J. Simpson’s “If I Did It,” an allegedly hypothetical account of the killing of Nicole Brown Simpson, was dropped by Regan Books, a division of HarperCollins, and then picked up by the independent publisher Kampmann & Company. More recently, in 2017, when alt-right shock scribe Milo Yiannopoulos suggested flippantly that pedophilia might be OK, Simon & Schuster dropped him like a name at a cocktail party. He later self-published, and wrote a follow-up title for Bombardier Books. Both Bombardier and Skyhorse distribute their books through Simon & Schuster, which had no comment for this article.

If we’ve been here before in book publishing, then why does the conversation seem so loud right now? It’s a sign of the times. The same forces that have polarized all of American culture — a deadly pandemic, unrest over police violence, a White House that sows chaos and disinformation — are polarizing publishing. Which is unfortunate because books, unlike, say, Twitter, are supposed to be the place we look to make sense of it all.

In 2020, even straightforward, shoe-leather stuff draws controversy. When Simon & Schuster published Bob Woodward’s “Rage” in September, revealing untoward if unsurprising behavior on the part of the president, both publisher and journalist took flak for sitting on the fact that Trump knew how damaging and infectious COVID-19 was in February. The case that it would have made a difference wasn’t nearly as strong as the rancor of the charge.

“The difference now is that the stakes have changed,” says Maris Kreizman, a writer and longtime publishing professional. “There is a war against news. And someone at some point has to say, ‘The buck stops here.’”

Skyhorse is almost comically agnostic on the truth; in fact, it will often stake out incompatible positions back to back, like a stockbroker shorting his own bets. The house published “The Case for Impeaching Trump” by Elizabeth Holtzman, and then “The Case Against Impeaching Trump” by Alan Dershowitz, “The Case Against Masks” by Mikovits and Kent Heckenlively and, coming soon, “The Case For Masks” by Dean Hashimoto.

Woodward’s journalism helped bring down Richard Nixon. But “Rage” it too ploddingly neutral and enamored of access to make a dent in this fallen age.

This philosophy cuts deeply against the grain of 2020, when even free-for-all social media platforms are flagging misinformation from questionable sources like the president. Is there really a responsible argument to be made against wearing a mask to limit coronavirus exposure? Does Mikovits, who was also featured in “Plandemic,” a viral film that posits COVID as a massive government conspiracy, deserve equal time?

Critics have called Skyhorse a bottom-feeder dressed up in “a libertarianism of convenience,” as one person told Vanity Fair. Lyons, perhaps predictably, disagrees. “There’s always danger in free speech, and there’s always danger in dialogue,” Lyons says. “But I think there would be a lot more danger if we didn’t have free speech.”

Kreizman isn’t buying it. “When you have to invoke the free-speech argument, you know you’re doing something shady,” she says. “The whole point of free speech isn’t that you’re supposed to be able to get a book deal, no matter what you say.”

“There are books that shouldn’t be published,” says Laura Hazard Owen, a former editorial assistant at Skyhorse who is now the editor of the Nieman Journalism Lab at Harvard University. “Sometimes, things are canceled for a reason. A publisher has the right to publish whatever they want to publish, but just because you can make money off of something doesn’t mean you should.”

“Disloyal,” by Donald Trump’s former lawyer and fixer, convicted for finance crimes and perjury, is a rake’s progress of a Trump loyalist betrayed.

It feels ironic, or maybe inevitable, that a house with a stable of authors facing #MeToo allegations is now dogged by such allegations itself. Owen, for one, was unsurprised. In interviews with The Times and in a Twitter thread, she recalled an editor, no longer with the company, who took her under his wing in 2007, plied her with drinks and made remarks she considered “toxic and manipulative” — yelling at her, critiquing her “insouciant rejoinders,” commenting on a thong she was wearing and offering to give her an annual review over drinks. Owen says that after she showed Lyons some of the editor’s emails, he replied, “It’s probably because I grew up in New York, but I was expecting to be shocked by these and I wasn’t.”

Lyons responds: “I never saw any evidence of sexual harassment and, in any case, Laura told me that she didn’t want me to do anything .... I assured her that she wouldn’t have to work with that editor again.”

Of the latest allegations, Owen says, “It sounds a lot like it was when I worked there. It was a dysfunctional work environment. I would not have thought a company with these issues would have survived. But it did.”

Indeed, Skyhorse has thrived. “Plague of Corruption” landed on the Amazon bestseller list. “Disloyal” debuted there at No. 1. In 2015, the house had revenue of $43 million and a backlist of 6,000 titles.

If Skyhorse has proved anything thus far, it’s that cancel culture isn’t as powerful as its publisher makes it out to be. Allen and Cohen and Keillor and Mikovits were published, after all; even after Vanity Fair went to town, no one — and nothing — was canceled. Among the upcoming Skyhorse titles by Dershowitz, who is something of a house writer: “Cancel Culture: The Latest Attack on Free Speech and Due Process,” out Oct. 15. Barring something extraordinary, Skyhorse will still be standing then. Cancel culture, in the end, has its limits.

‘Plandemic’ director Mikki Willis explains why he made the controversial coronavirus documentary.

Vognar writes about books and culture for Kirkus and other publications.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.