Review: A Swiss storyteller whose clockwork precision gives his mad characters free reign

On the Shelf

'It's Getting Dark: Stories'

By Peter Stamm

Translated by Michael Hofmann

Other Press: 240 pages, $23

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

An author’s appearance is rarely relevant to a review of his work, but in the case of the Swiss novelist Peter Stamm, a facial feature might provide a clue not just to his new story collection, “It’s Getting Dark,” but to his entire oeuvre.

Stamm, 58, appears in almost every photo, posed and candid, with his mouth firmly shut. That doesn’t mean he isn’t smiling; he often is. However, in the few pictures where he laughs, he looks like a different person.

Here, you sense, is an author schooled in self-concealment. In his novels and his short fiction, Stamm writes in characters’ voices so different from his own — and from each other’s — they seem to have no author at all. In 2014’s novel “All Days Are Night,” a television broadcaster named Gillian has been in the hospital after a car accident that left her husband dead and her face disfigured. The slender plot rests on Gillian’s reckoning with a new appearance and, perhaps, a new identity. Rich fodder for authorial intrusion, yet Stamm remains staunchly inside Gillian’s consciousness.

Perhaps that seems right for a first-person narrative, but Stamm remains just as closemouthed across all his work. “It’s Getting Dark,” translated into English by Michael Hofmann, includes stories told in third person as well as first, in the present and in memory. Yet they all feel as if the characters are in the room with you, or on a screen. You may loathe one or another (the man who narrates “Marcia From Vermont,” or the one who lusts after a teenager in “My Blood for You”), but you believe in them all the same.

Coming in December: Unsparing memoirs about very messy relationships; globe-spanning new fiction from Nadifa Mohamed, Tom Bissell and others.

Perhaps this is why Stamm has (wrongly, to my mind) been labeled by critics as “bloodless” and “undemonstrative” and “cold.” Yes, his prose has the precision of his country’s famous watches. Yes, his characters often do things — cheating, leaving, hurting, stealing — that would make the Roys of HBO’s “Succession” look like kids on a playground. But you never stop and think, “This is preposterous, this could never happen, no one acts like that.” If this is cold, you feel, perhaps reality is at fault.

Consider “Marcia From Vermont,” the first and longest piece in this collection. Its original German title includes the subtitle “A Christmas Story.” Omitting it is a curious choice, though perhaps the connotation is too sunny in English for the darkness at hand.

“Marcia,” like quite a few of the other stories here, concerns the downfall or dissolution of a middle-aged man. The author who narrates “Marcia” looks back on a long, lonely artistic residency he once had in Vermont that culminated in a strangely erotic tangle with a woman named Marcia and a couple of her friends. While he doesn’t end up ruined, he does wind up less of a human than he could have been.

“Supermoon” shows us a middle manager — the sort Stamm himself might have become if he hadn’t quit being an accountant to write — slowly disintegrating as he nears retirement. He is tight-lipped, preferring to project competence and bonhomie rather than engage in conflict or growth. First, he notices that people on the train don’t notice him. Then he speaks to his wife and gets no response. Although he continues to shop and eat, soon he can’t even muster the strength to unlock his door. He’s the opposite of a werewolf, someone whose energy wanes without the corporate structure that rules the light of day.

“It’s Getting Dark” is the title of a different story in the collection but it could apply here, and it resonates across the stories in all its connotations. It evokes winter. The steady progress of climate change. A generation’s end. Even a gender’s obsolescence as it rages against the dying of the light. From the “Marcia” narrator to the ailing physician in “The Woman in the Green Coat” to the paterfamilias in “First Snow,” many of the author’s men take too much for granted in their lives, bringing no end of darkness onto themselves and others.

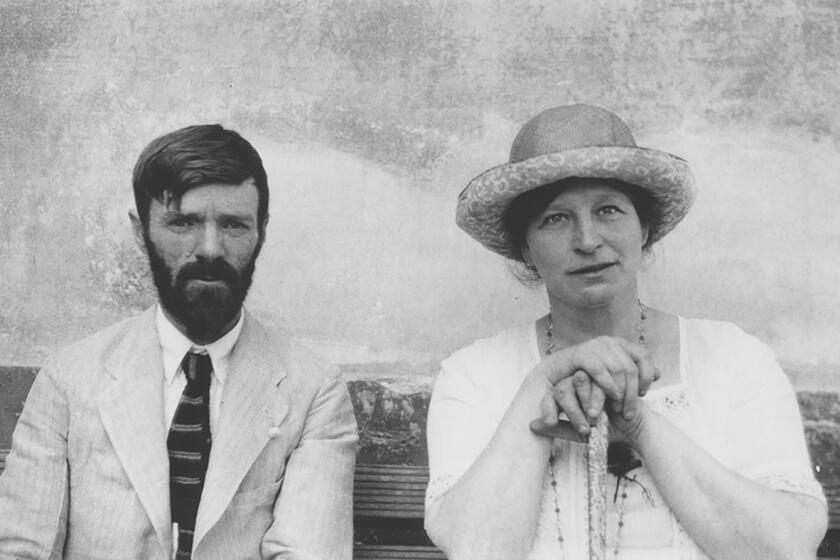

A new Lawrence biography, “Burning Man,” by Frances Wilson, and Rachel Cusk’s novel “Second Place” turn the toxic male author into rich material.

Equally strange and compelling are the reactions of women (at least the heterosexual ones) to these men. Why does Sabine, in “Dietrich’s Knee,” fall for her live-in boyfriend’s betrayal, even after she herself has betrayed him? Stamm knows people aren’t rational. The ending of “Sabrina, 2019” shocks: A young woman’s true-to-life cast-metal sculpture winds up in a mansion — and she decides to wind up there too. But the “What was she thinking?!” reaction belongs entirely to the reader. To that woman, as real as every other Stamm character, her fate makes perfect sense.

If Stamm’s prose appears to some as “bloodless” and “cold,” might that be because it unspools almost like reportage? He’s a journalist embedded on the front lines of his characters’ psyches, not invested in manipulating their choices according to theme. Or, at least, that’s how he manipulates us, even as he builds his themes with a hidden smile.

One of the collection’s most surprising stories is “The Most Beautiful Dress,” in which it seems another young woman is driven to a kind of love-mad recklessness. If you underestimate Stamm, you’ll predict one kind of ending. But if you remain open to the idea that even reticent writers can contain multitudes, the ending will make perfect sense. “It’s Getting Dark” is vintage Stamm, a story collection predicated on how humans behave, not how we might like them to behave. Case closed, mouth shut, eyes wide open to see the truth.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.