Appreciation: How Joan Didion punctured California narratives about manifest destiny ... with a potato masher

Can a single object contain within it the narratives of a family and an entire nation? If so, for Joan Didion that item may have been a potato masher.

The masher in question — a humble kitchen implement whose creation dates to the first half of the 19th century — made the arduous overland journey west some time in 1846-47 with her ancestors, the Cornwalls. They were a faction of the Donner-Reed Party that had been smart (or lucky) enough to make for Oregon instead of California once they hit Humboldt Sink, Nev., thereby avoiding a winter impasse in the Sierra Nevada, not to mention one of the most infamous episodes of cannibalism in American history.

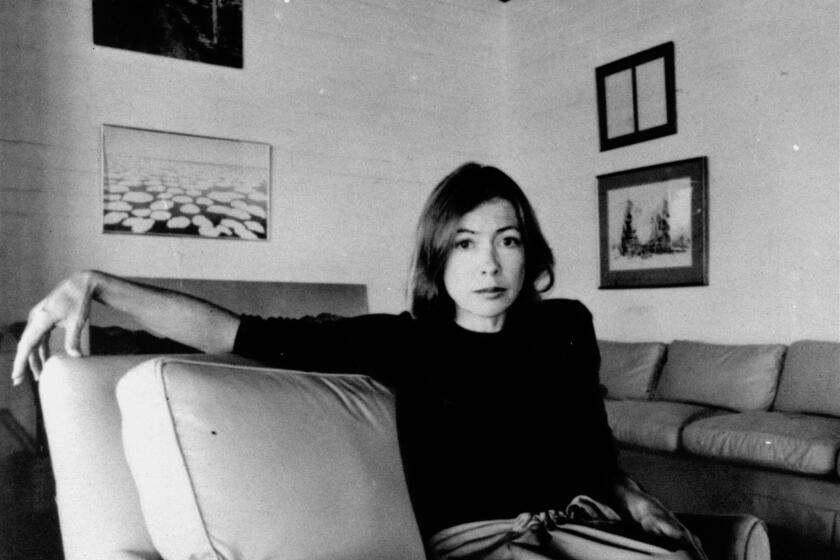

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

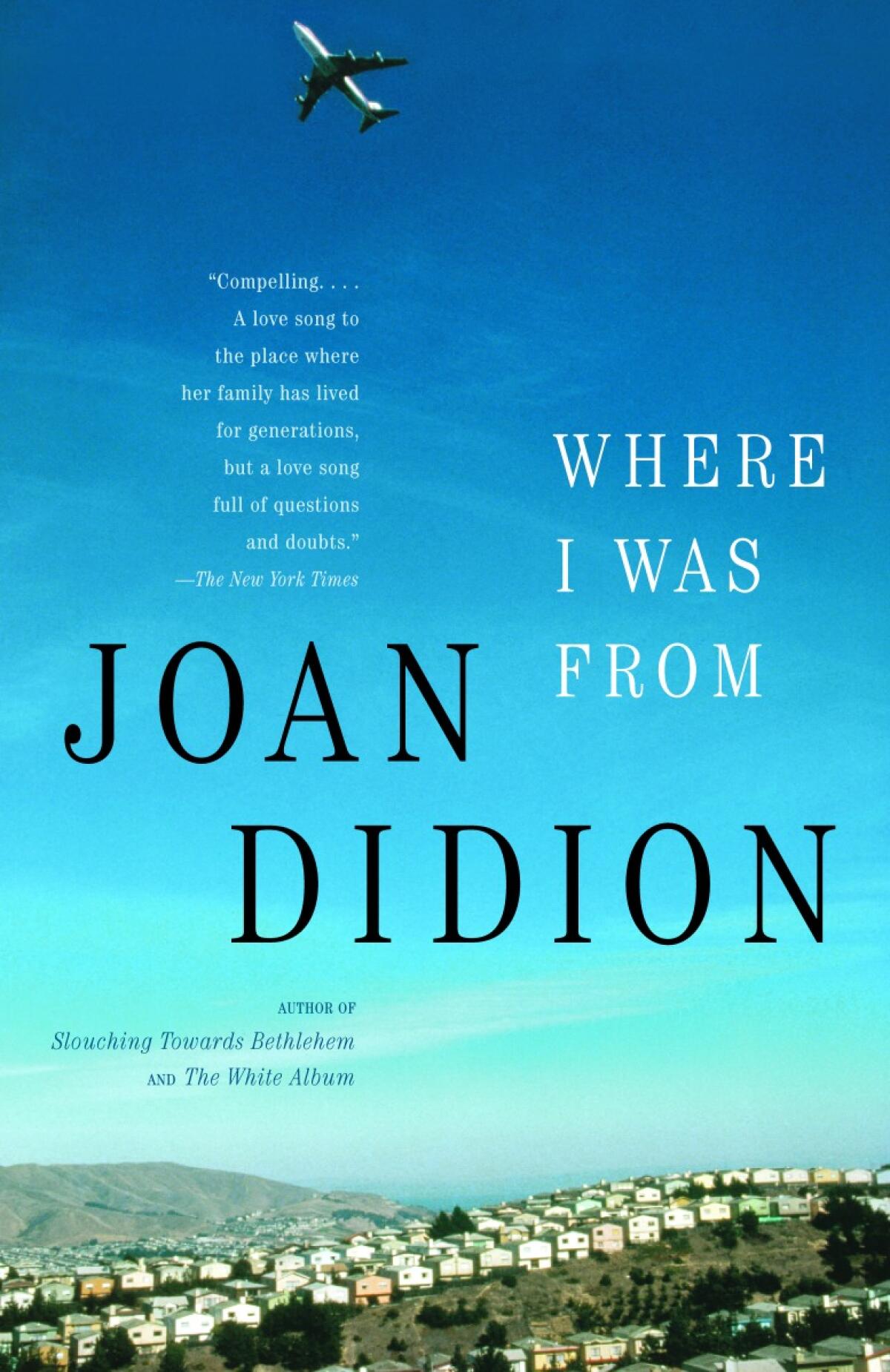

Sacralized by family lore and more than a century and a half of American history, the masher served as deadpan literary device for Didion in her 2003 nonfiction collection about California, “Where I Was From.” She writes of a relative, Oliver Huston, “a family historian so ardent that as recently as 1957 he was alerting descendants to ‘an occasion which no heir should miss,’ the presentation to the Pacific University Museum of, among other artifacts, ‘the old potato masher which the Cornwall family brought across the plains in 1846.’”

“I have not myself found occasion to visit the potato masher,” Didion declares dryly. But the masher nonetheless makes several appearances in her book — and its looming presence is even echoed in its final paragraphs.

I have been unable to determine whether Didion ever laid eyes on the masher of manifest destiny. But thanks to an archivist, as well as a communications rep at Pacific University, a small liberal arts college in Forest Grove, Ore., who gamely responded to my rather preposterous email about a potato masher on Christmas Eve, I was able to ascertain that it remains in the museum collection — along with other 19th century objects donated by Huston, including a handbag, a black cape and a lap desk. (Unfortunately, I was unable to secure a photo in time for this story, since the campus is closed for the holidays.)

The overland crossing is such a hallowed narrative in American history that it can render an object as mundane as a potato masher preservation-worthy. And it is precisely that narrative that Didion tackles in the unblinking “Where I Was From,” which like many of Didion’s works actually began as a magazine article: “The Golden Land,” a 1993 essay published in the New York Review of Books.

Didion, who died last week at the age of 87, was a master of tugging at the threads of established narratives until nothing was left but a tangled heap. Her exquisite piece “Insider Baseball,” also for the New York Review of Books (and one of my favorites), found her on the 1988 presidential campaign trail, the year of George H.W. Bush versus Michael Dukakis. In the piece, she witheringly compared the humdrum reality of campaign events to the puffed-up conventional wisdom that the Washington press corps was passing off as reporting. Her analysis of Martha Stewart’s popularity in a 2000 piece for the New Yorker poked through the façade of homemaking superwoman to reveal a brand built not on cozy dinner parties but corporate domination.

In “Where I Was From,” Didion methodically takes a seam ripper to the psyche of California, a state whose modern, Anglo identity is built on a narrative of hardy can-do spirit, one shaped by a rigorous overland crossing that, as she writes, had undertones of a “moral or spiritual” test. “Each arriving traveler had been, by definition, reborn in the wilderness,” she wrote, “a new creature in no way the same as the man or woman or even child who had left Independence or St. Joseph however many months before.”

In other words, a journey that could make of a potato masher a revered historical artifact.

Yet, as Didion also coolly points out, this identity of extreme self-reliance was built not simply of individual rigor but also on the handsome subsidy of the U.S. federal government. The construction of railroad and water infrastructure in the 19th century — and the economies supported by the lucrative defense industry of the 20th century — all of that came courtesy of intensive taxpayer investment.

“This extreme reliance of California on federal money, so seemingly at odds with the emphasis on unfettered individualism that constitutes the local core belief, was a pattern set early on,” she noted in the book, “and derived in part from the very individualism it would seem to belie.”

“Where I Was From” also folds in and expands her 1993 New Yorker essay “Trouble in Lakewood,” which examines the lives of a group of dissolute teens against a backdrop of the plunging aspirations of Southern California’s middle class as the defense industry withdraws from the region. These are narratives she dexterously braids with William Faulkner’s “The Golden Land,” which, if not Faulkner’s best work, paints a cautionary picture of youthful libertinage in sunny Los Angeles.

Where most writers saw a plant closing, Didion saw an opportunity to explore the political and psychological forces that shaped California — forces that had become its undoing.

Joan Didion continues to resonate in California, even with a generation nothing like her.

If “Where I Was From” has a shortcoming, it’s that it fails to acknowledge the stories that may have been overwritten by the culture-saturating narrative of the westward ho — subject of innumerable novels, paintings, TV shows, movies and historical accounts.

This was on my mind in 2017 when I went to see a multimedia installation by filmmaker Alejandro González Iñárritu at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Part virtual reality experience, part sculptural installation, “Carne y Arena” explored the nature of the perilous desert crossing undertaken by countless Latin American immigrants to the United States. At the time I saw the work, I had recently reread “Where I Was From” and was intrigued by the idea that we live in a culture that venerates some crossings — the arrival of the Mayflower pilgrims, westward expansion — while ignoring or vilifying others: the forced migrations of Indigenous people, the Atlantic crossings survived by Africans kidnapped for slavery, the fatal journeys made by Haitians in the Florida straits, the epic treks made by Mexicans and Central Americans who take to the arid Sonora in hopes of building a better life for their children.

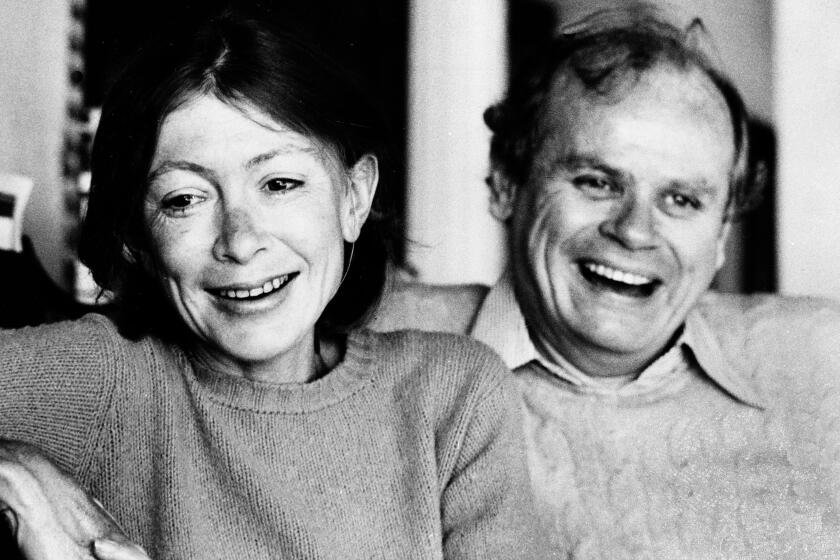

Yes, Morrison’s pants were leather. Yes, Densmore slept with Eve — and other questions answered as the Doors drummer remembers L.A.’s two writer-icons.

I don’t expect a single writer would ever be able to cover the breadth of our knotty history in a single work. But Didion laid an important foundation by puncturing some of our most sacred national myths. And where her works ended, others begin.

I think of Luis Alberto Urrea’s gripping book, “The Devil’s Highway,” which was published just one year after “Where I Was From” and recounts the tale of a group of immigrants abandoned in the desert by an unscrupulous coyote. “Europeans conquering North America hustled west, where the open land lay,” writes Urrea. “And the Europeans settling Mexico hustled north. Where the open land was. Immigration, the drive northward, is a white phenomenon. White Europeans conceived of and launched El Norte mania, just as white Europeans inhabiting the United States today bemoan it.”

I also think of poet Marcelo Hernandez Castillo’s memoir, “Children of the Land,” published last year, with its aching descriptions of his parents’ desert ordeals: “When they crossed in the the U.S., they wandered the desert alone for miles without food or water. They were still young; maybe they still loved each other, or would soon start to. Every direction seemed like it was north, as if it was always noon in their heads. They moved because regardless which direction they faced, they trusted what was ahead more than what was behind them.”

Any story is a fragile architecture of inclusions and elisions. What made Didion’s work so important is that she was unafraid to dismantle that architecture. She took many of the most pervasive and accepted narratives of our culture and subjected them to exacting stress tests. In her hands, old tribal myths of self-reliance crumbled. What she gave us in their stead was an exquisitely erudite yet brutally unflinching look at ourselves — and the potato mashers to which we so often cling.

The Pritzker Prize-winning designer, who died Saturday at 88, was influenced by the Case Study Houses, but critical of L.A. sprawl.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.