Always on the edge, an unflinching memoirist leaps off into fiction

On the Shelf

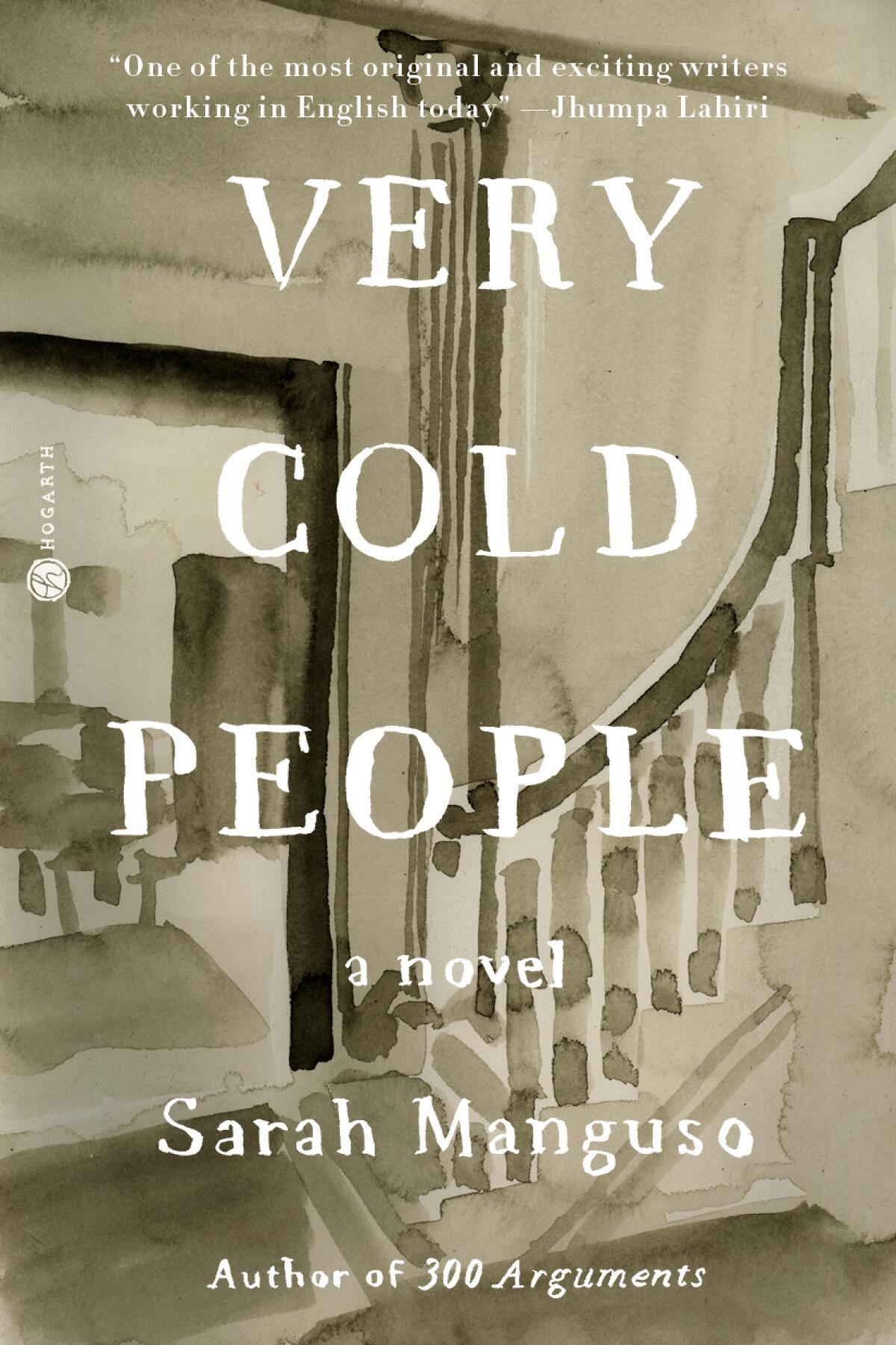

Very Cold People

By Sarah Manguso

Hogarth: 208 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

At the end of Sarah Manguso’s ninth book (and first novel) “Very Cold People,” Ruthie visits the small colonial cemetery near her childhood home. “Patience, one of my favorite gravestones read. That’s all it said. It was a baby’s grave. Impatient little thing! She got out of Waitsfield before almost anyone.” Though Ruthie did escape, and was away from her hometown for years, she has waited for release from its wraithlike grasp.

It was an unseasonably cold and blustery day in Santa Monica when I visited Manguso at her home to talk about her first foray into fiction. The crossing guard in front of Manguso’s house was bundled up in a parka one might wear for an Arctic expedition. The house was surrounded by a petite white picket fence. Though Manguso has lived in California for many years, the East Coast, the land of the very cold people, is very much a part of her makeup. She is not, you might say, a California girl, though California suits her nonetheless.

Manguso started her career as a poet. In 2008 she published a memoir, “The Two Kinds of Decay,” about her experience with an autoimmune disorder that nearly killed her. The book looks directly, unflinching, at the blood draw, the placement of the central line, the sheer horror of being that close to death. “The Guardians” recounted the story of her friend Harris, who took his own life by jumping in front of a commuter train. Most recently, Manguso has published “Ongoingness,” a diary on keeping a diary, and “300 Arguments,” exactly what it sounds like.

Reading Manguso is like watching someone skin an animal, slice its throat and drain its blood, preparing it quickly and efficiently for consumption. You wonder, reading her succinct and devastating sentences, just what she had to do to get there.

In “300 Arguments,” she writes: “I used to pursue the usual things — sex, drugs, rough neighborhoods — in order to enjoy the feeling of wasting my life, of tempting danger. Motherhood has finally satisfied that hunger. It’s a self-obliteration that never stops and no one notices.” And then, simply: “Inner beauty can fade, too.”

“I never thought I would write a novel,” she told me. “Yet I’ve been able to articulate something about this culture that I hadn’t been able to. I’ve learned a few things about what fiction can do that nonfiction can’t. It was incredibly freeing. This is a real turning point for me as a writer. My books were getting shorter and shorter. I initially began the book as a memoir, but there wasn’t enough story there. I ran out of material!”

Here’s the question at the heart of Sarah Manguso’s “Ongoingness: The End of a Diary” (Graywolf: 98 pp., $20): How does a writer record his or her experiences and live them at the same time?

The fictional and appropriately named Waitsfield is an all-white town in suburban Massachusetts. Ruthie’s mother is waiting for her delusions of grandeur to become real, but her family is poor. They drink powdered milk. They take trips to the town dump to find school supplies and books, and when Ruthie’s mother discovers a catalog for fancy watches, she irons it and places it on the coffee table so it looks casually tossed aside.

The emotional violence of Ruthie’s family hums in the background like a running refrigerator. A cut goes unattended, gets infected and requires antibiotics. Her parents’ emphatic neglect seems normal to Ruthie, and in this town it is. One of Ruthie’s friends still takes showers with her father. Another has a baby with her half-brother. Still another died by suicide.

“Back then, it would have sounded extremist, paranoid, delusional, to say that all attention to girls was tinged with sex,” Ruthie reflects. “And so when the gym teacher put his hand on my ass, moved it around as if trying to get the dimensions of it … I thought, How old-fashioned and almost tender, this so-called molestation.”

In “Very Cold People,” as Manguso explained, “The abuse wasn’t the story. The abuse was the setting. It’s elemental.”

Ruthie escapes by imagining a different world. She invents a character who takes up two middle chapters: a woman who lived in her house before her — Winifred Cabot Fish. She imagines her embarking on an affair with the teenage boy next door after her husband’s mysterious death.

“Winifred becomes a character that lives completely in Ruthie’s imagination. Ruthie owns her,” Manguso said. “In fact, these were the first two chapters I wrote of the book. But then I realized she could be a tool, this metaphysical origin story of Ruthie getting out of Waitsfield. This is the first freedom that Ruthie has.” Though Manguso didn’t go so far as to say it, Ruthie’s imagining of Winifred is a kind of writing.

It’s tempting to ask the author if writing once provided the same escape. Given that Manguso was born near Boston in 1974 and attended grade school in a town and era much like Ruthie’s, readers might be inclined to assume autobiographical sources.

Kate Zambreno’s process is rumination and frenzy. That’s how she completed “To Write as if Already Dead,” an homage to the late writer Hervé Guibert.

“I want to be very clear that this book is not about me or my family,” Manguso said. The experiences are real only in the most abstract sense — or rather in the most specific. “I really value my sensory experience,” she says, which explains why the book is rich in visceral descriptions, sights and smells. “Of course it would make sense that I would put Ruthie in this place and time. But I didn’t want to write a novel with a character that readers would map onto me.”

It’s the opposite conundrum from the memoirist’s — an irony that makes Manguso laugh: “It’s such a tidy theorem. Memoirs are all packs of lies, and novels are all inherently true!” The real truth is that, for a poet and memoirist, fiction feels like an escape from autobiography, a chance to encompass a larger world beyond personal experience.

“This book has haunted me for a long time,” Manguso said. “I believed in my ability to write ‘the big book.’ I called it ‘my Boston book.’ I even wrote ‘300 Arguments’ as a no-no, hooky project to distract myself from ‘the big book.’ But this is not the ‘Boston book.’ There might be 10 Boston books! And if I ever write ‘the Boston book,’ I’ll probably immediately die.” Manguso already has a draft of her next novel.

Ruthie escapes Waitsfield, but not without a climactic affirmation of its horrors, of the unspoken violence of the very cold people. “I’ve been thinking about whether or not this is a hopeless book,” Manguso said, smiling. “Someone asked me where the hope is in this book.”

Bethanne Patrick’s February picks include two Nobel Prize winners, tales of Hollywood then and now, a new African fantasy epic and much more.

She paused, and I asked: “Does there have to be hope?”

“That’s a good question to ask,” she nodded. “Ruthie learns that some structures cannot be changed. And some people can never be reached. That the only thing to do is to disengage. And that’s the tool that gets her out. I see that as a message — well, not a message, maybe — but as a swath that runs through the book: a large ribbon of hope.”

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.