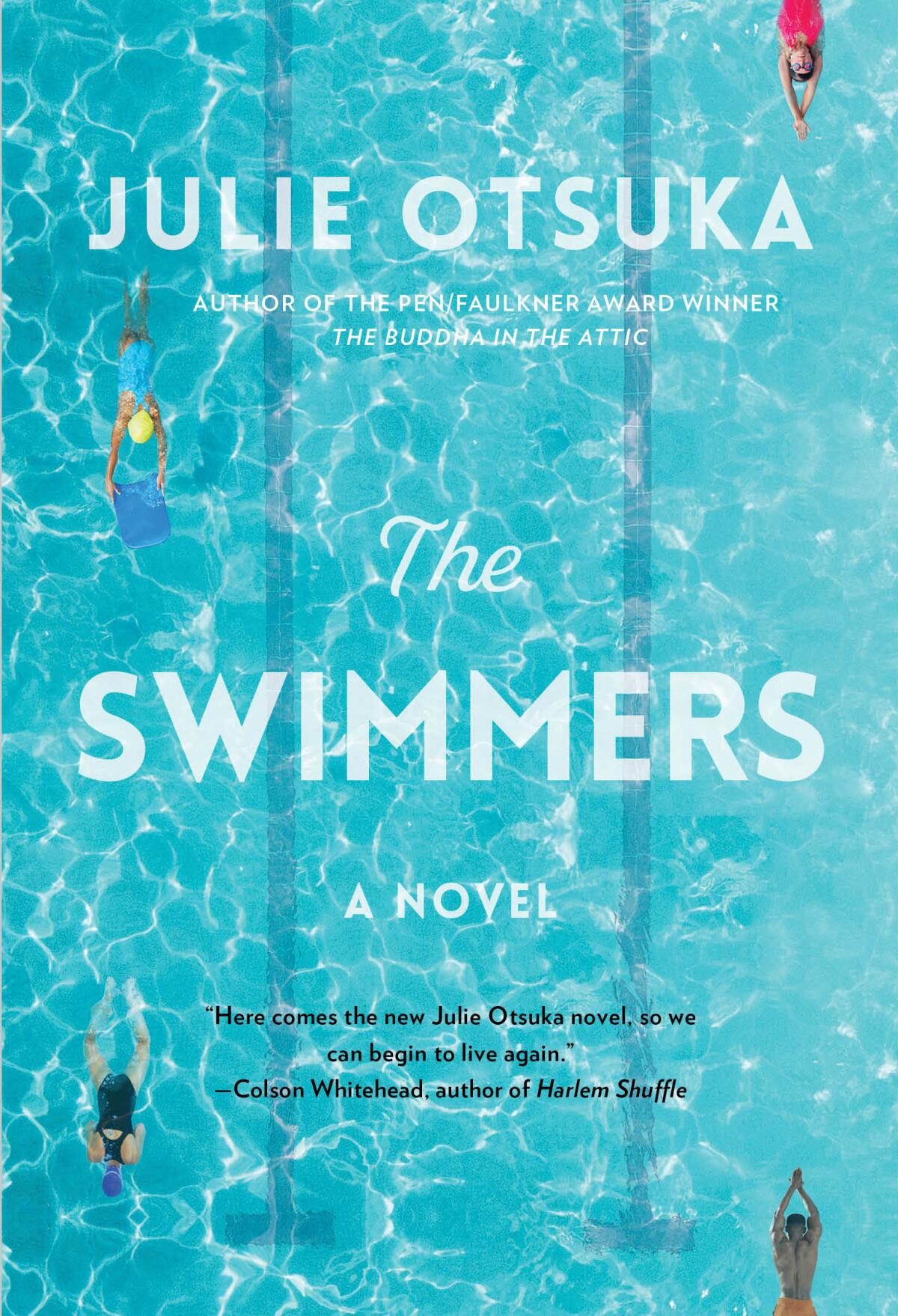

Review: A survivor of internment sinks into forgetting in Julie Otsuka’s ‘The Swimmers’

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Swimmers

By Julie Otsuka

Knopf: 192 pages, $23

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Does the community pool have magical powers? It’s easy to think so, reading the opening section of Julie Otsuka’s third novel, “The Swimmers.” The book begins with a quirkily exultant 30-page ode, relayed in the first person plural and filled with the author’s signature lists. “In our ‘real lives,’” Otsuka writes, “we are overeaters, underachievers, dog walkers, cross-dressers, compulsive knitters (Just one more row), secret hoarders, minor poets, trailing spouses, twins, vegans, ‘Mom,’... .” But once in the water, swimmers are only “one of three things: fast-lane people, medium-lane people or the slow.”

At this subterranean pool in an unnamed university town, water has a radical effect. It exerts its buoyant force on bodies, easing pain and making the old feel young. Swimmers find escape from the “usual aboveground afflictions” — knee problems, addiction, heartbreak. Differences among people are washed clean. Rules are a comfort, because they mean that the pool is always the same: a refuge from noise, family, work, the internet, the “too-bright sun beating down through the tattered canopy of the trees.”

The cultish devotion among Otsuka’s swimmers sometimes strains credulity. Do the interlopers who briefly join the pool in January to shed holiday pounds really say “Out of my way, lady” to poor sweet Alice, who has dementia? Would a swimmer who seeks to hoard the mysteries of the pool, rather than share them with a curious partner, ever actually change the subject by asking, “Why do you think those dinosaurs really disappeared?”

We get it: Pool people are all in. Hard core. But Otsuka, who is well known for her two previous novels, “When the Emperor was Divine” and “The Buddha in the Attic,” is up to more than mere amusement. A master of shifting perspective, she is preparing us for a rift.

Just as the reader settles into this amusing, intimate study of a microcosm, a crack appears on the wall of the pool and the book makes a flip turn. At first, the swimmers “mistake it for something else: a piece of string, a length of wire, a scratch on the outer lens of our goggles.” But the crack is real, a literal fault line in the fantasy world of the pool.

Though “no longer than a child’s forearm,” the crack lodges itself in the swimmers’ minds, and the community promptly disintegrates around it. Here, “The Swimmers” reminded me of “Desperate Characters,” Paula Fox’s taut 1970 novel, where a bite on the hand from a stray cat unravels a woman’s life over the course of a weekend.

The Norwegian novelist’s latest, ‘Men in My Situation,’ has its share of male myopia but transcends when it encompasses universal conditions.

One important difference is that Otsuka treats the omen with humor, infusing the narrative with the absurdist quality of a small-town mystery. There are subterranean structures specialists and aquatics commissioners. A swimmer who is a medical claims adjuster calls the crack a preexisting condition. “Oy,” I groaned, at the rabbi who says the crack is “but a minor misfortune in a long string of continuous woes.” These characterizations are flattening, but Otsuka is always poetic too: “Last night I dreamed I had a splinter in my eye,” says one character.

The person most affected by the crack is Alice, the regular lap swimmer with dementia, who experiences flashbacks to her wartime childhood incarceration in a camp for Japanese Americans. Alice becomes the center of the novel, and her presence seems to be the only connection between the two compelling but disjointed halves of this book. One section in the second half, called “Diem Perdidi,” Latin for “I have lost a day,” is an exhaustive summary of all that Alice can and cannot remember relayed by her daughter. (“She remembers that the daughter who was born before you lived for half an hour and then died.”)

The following section, “Belavista,” finds Alice in a long-term memory residence by this name (off a freeway, by a mall). Most of this section is addressed to “you” (Alice) and delivered by a different and more elusive “we” than the book’s first half. Presumably, it’s the facility itself or some group of representatives therein, but in this instance Otsuka’s play with perspective can be slightly confusing. Sometimes it’s omniscient, sometimes more specific (maybe Alice’s daughter)? Ultimately it doesn’t make consistent sense.

Nevertheless, a theme coheres. Descriptions of Belavista form a grim counterpoint to the freedoms of the pool. The frustrations of life “up there,” which fell away in Alice’s 35 years of swimming, form the substance of every day at the residence. When it comes to who you were before, in your so-called real life, “Nobody knows and nobody cares,” Otsuka writes.

It’s the kind of paradoxically hyper-surveilled but deeply lonely existence we associate with prison. Nightlights come on automatically at eight o’clock every night (“you will never experience total darkness again”). There is a Life Enrichment Manager named Jessica. Otsuka is a master of heartbreaking detail, and the reader feels sentenced, along with Alice, to this dreary, for-profit last stop.

Claire-Louise Bennett’s second novel, ‘Checkout 19,’ eschews moralizing to reveal, with beauty and humor, a narrator hopelesly entangled in reading.

Both of Otsuka’s previous novels deal with the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. The profoundly moving “Buddha in the Attic,” which won a PEN/Faulkner Award and was nominated for a National Book Award in 2011, is about Japanese “picture brides” who came to America to marry men they’d never met and who worked as migrant laborers or domestics in white homes in California.

“Buddha” is also written in first-person plural, to devastating effect. Girls and women endure a harrowing oversea journey followed by the disappointments of meeting often much older husbands, as well as sexual violence, poverty, exploitation and racism. They raise American children only to become a source of embarrassment for their stubborn accents or the food they pack in school lunches.

In “The Swimmers,” Otsuka uses the first-person plural — the resounding style of grand oratory, political pamphlets and fundraising appeals — to enumerate the dizzying specificities of human lives. Her packed paragraphs are often-thrilling compilations of detail, even when she’s just listing items lost at the bottom of a pool (cotton balls, wedding rings, German marks).

The novel is filled with these tender assemblages, a declarative chorus of human tastes, memories and woes. But the proliferation of detail in “The Buddha in the Attic” grants depth and sorrow to its characters. That’s a feat only achieved in the later sections, where Alice’s life comes into focus.

For all of its expansive details, “The Swimmers” is sometimes twee in its first half. Even as it deals with “aboveground” troubles like dementia, the world of the book — speaking of lives suspended in water — feels a bit like a snow globe. Its often-captivating insularity can also be cloying at times. As in her earlier work, the heavier the themes, the more Otsuka’s language lifts off. Once we are squarely in Alice’s world, “The Swimmers” sparkles.

Nina Renata Aron’s memoir, “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls,” doubles as an ennobling history of recovering enablers of addiction.

Aron is the author of “Good Morning, Destroyer of Men’s Souls: A Memoir of Women, Addiction, and Love.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.