Review: How cosmetic surgery emerged from the horrors of World War I

On the Shelf

The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeon's Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

By Lindsey Fitzharris

FSG: 336 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“The man had almost no face left; a bullet had hit his mouth and exploded, blasting through his cheeks, shattering his jaws, ripping out his tongue, a bit of which was hanging down, and the blood gushed abundantly from these horrible wounds,” a witness wrote after battle. The man had lived, but he wondered “would even his own mother have recognized him in a state like that?”

Cosmetic surgery, nowadays more commonly associated with elective procedures for the wealthy and vain, in fact evolved under the most brutal conditions and with the noblest of aims. In “The Facemaker,” Lindsey Fitzharris offers a fascinating medical history of the development of the discipline. Its catalyst was World War I, when modern, mechanized weapons destroyed flesh more efficiently than ever before and doctors struggled to keep up.

“Unlike amputees, men whose facial features were disfigured were not necessarily celebrated as heroes,” Fitzharris writes. “Whereas a missing leg might elicit sympathy and respect, a damaged face often caused feelings of revulsion and disgust.” The 280,000 men who returned with such injuries were seen to have suffered a fate worse than dying on the battlefield. Referred to as “les gueules casées” (broken faces) in France, they triggered primal emotions and beliefs about the link between the visage and the soul.

Mechanized warfare is the mind-body problem writ large. As the methods of science and engineering progressed to create killing machines, they forced people to distance themselves from the disfigurement that followed. But they also challenged those in medicine to fix the body in ways that could soothe the mind. Physicians who entered this new terrain had to combine the science of medicine with the art of reconstruction, sculpting and healing.

Among these pioneers was Harold Gillies, a British doctor who invented techniques to treat horrific facial injuries. Born in 1882, Gillies lived a comfortable life as a London surgeon with a focus on issues of the ear, nose and throat. After the war started, he volunteered and was sent to France in January 1915. There he met Auguste Charles Valadier, a French-American who had returned to France to practice dentistry.

Cosmetic professionals tell The Times that a lot of people are undergoing procedures during the pandemic. While that might seem random at first, when you look a little deeper, it makes sense.

On the front, Valadier saw that his dental skills were needed to treat more than rotten molars. Gillies observed the dentist using bone grafts to repair injured jaws and realized they were crucial to rebuilding recognizable faces. Valadier, Fitzharris writes, “took a section of a patient’s rib and inserted it beneath the flesh of his forehead in order to reconstruct the soldier’s nose. Once the graft took hold, Valadier reshaped the skin around it.”

As Fitzharris works her way through various types of trauma — missing noses, amputated jaws, burns that charred the entire face — she chronicles the rise of the various medical arts brought to bear in treating them. She threads into such discussions cultural commentary and a social history of ableist notions of beauty and health.

In the development of rhinoplasty, for example, citing scholars such as Sander Gilman, Fitzharris shows how a person’s nose became a marker of their health. Since late-stage syphilis attacked the nose, those so afflicted were seen as bearing proof of moral turpitude. The large-scale maiming of soldiers reminded civilians of the depravity of modern war. World War I had garnered tremendous support across Europe; those who had paid the price for civilians’ jingoism were treated as monstrous in part, Fitzharris argues, as a manifestation of collective guilt.

But the face is more than a symbol; it is the basis of human communication. The visual clues sighted people take from the position of an eyebrow or the perceived sincerity of a smile are given more weight than we acknowledge. Facially injured men were not just objects of revulsion; they were cut off from normative forms of social interaction. Across Europe, the unwounded preferred that such men remove themselves from society.

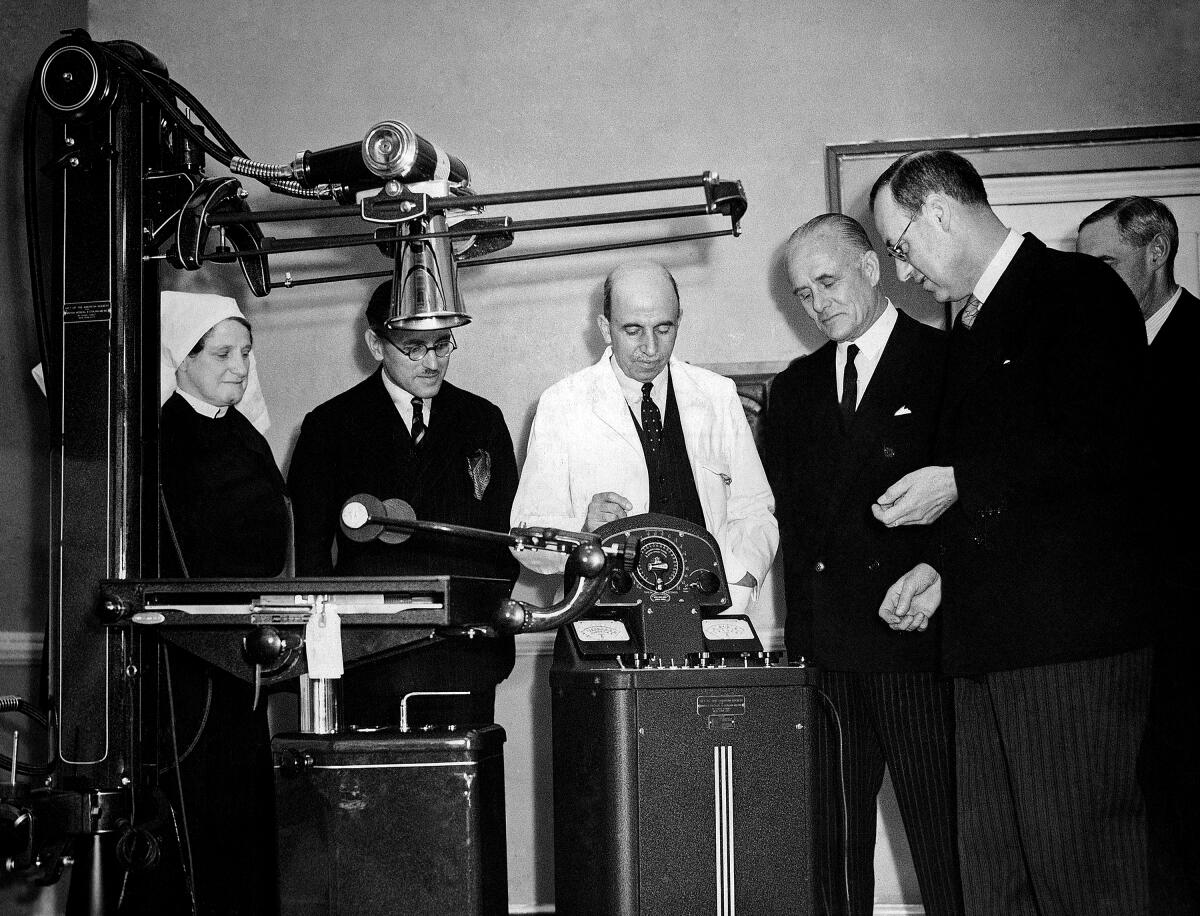

In addition to pioneering surgical techniques during the conflict, Gillies campaigned for specialized hospitals where men with facial wounds could be treated. These hospitals became more than just centers for research; they served as social spaces where patients felt unencumbered by the need to protect those who were repulsed by their wounds. They were rehabilitation centers, providing recreation and access to art, music and drama as well as access to new skills such as woodworking that would serve the men in postwar life.

‘Uncertain Ground’ collects Marine and novelist Phil Klay’s essays on how we redefine citizenship and other fuzzy concepts as a nation forever at war.

Fitzharris successfully balances the story of plastic surgery’s growth with a compassionate attention to those whose wounds made it possible. Photos that document the “before and after” faces of patients are chosen with due care, including the decision not to publish photographs of those who would later die of their wounds. Fitzharris follows the lives of the patients after they were discharged from the hospital. Many of these stories had happy endings, with Gillies’ patients going on to satisfying family lives and careers.

Histories of World War I are deeply personal to me. My great-grandfather, Robert Raymond, died in October 1917 of wounds sustained at Passchendaele, during a battle that killed or wounded 600,000 soldiers over three months. My grandmother was 10 months old when her father died, a common story in the U.K., which lost nearly 800,000 men and had 1.6 million wounded — an entire generation of young men who became casualties of older men’s disastrous decisions.

Robert died in a clearing station while being tended by the types of caregivers to whom Fitzharris pays tribute. In a time when changing one’s look to meet the latest Instagram trend is ridiculously easy for those can afford it, it is jarring to remember the terrible human price paid for the advancement of cosmetic surgery. But those clearing stations are the legacy I honor most. They still operate on the front lines of a society in which we still ask doctors to repair the horrific damage done to body and soul by readily available weapons of war.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

Not only our politicians and police are cowards about guns — we all are.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.