How the authors of ‘South Central Noir’ captured South L.A. and created a genre

- Share via

On the Shelf

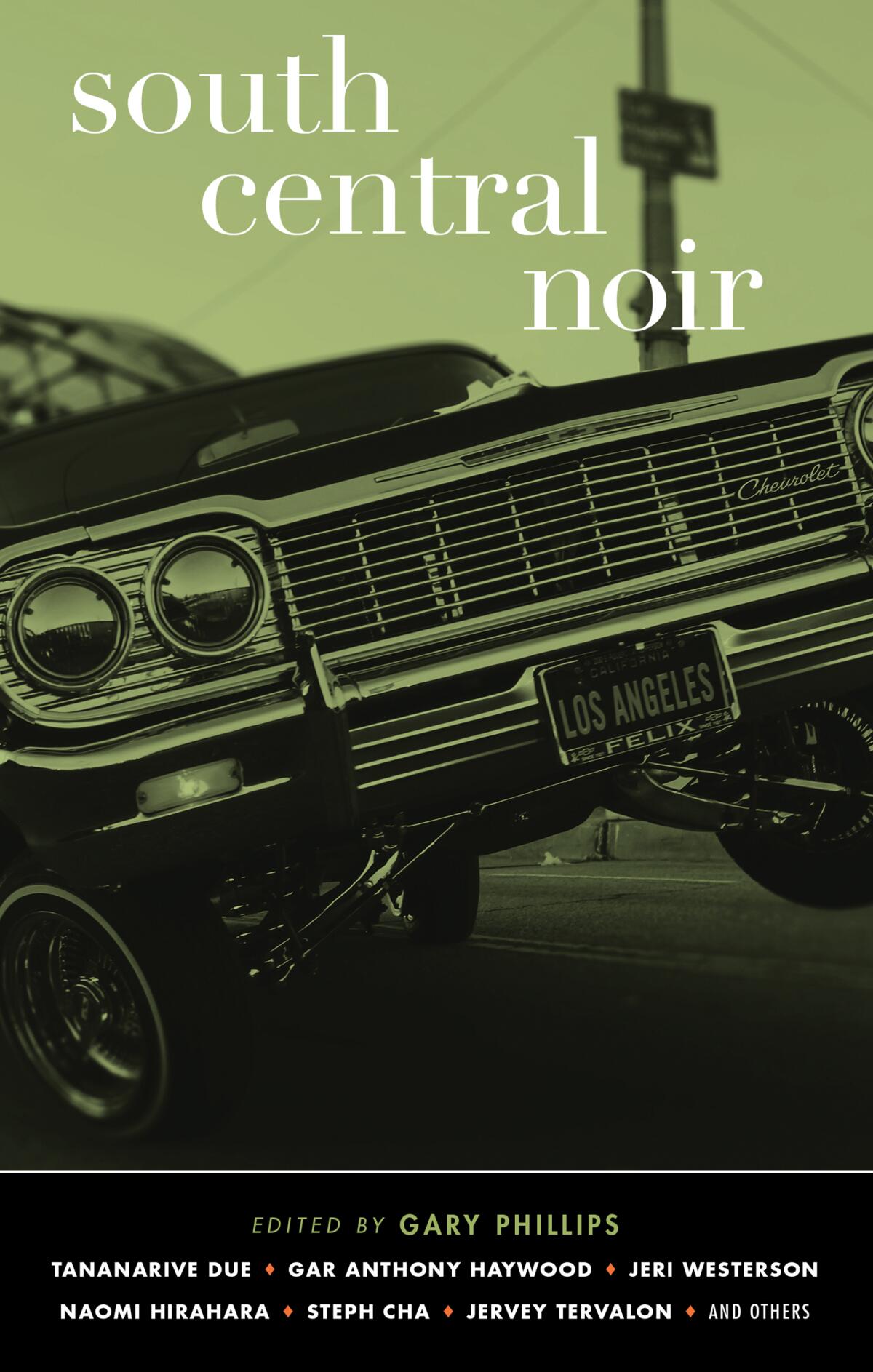

South Central Noir

Edited by Gary Phillips

Akashic: 280 pages, $17

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

If you’re of a certain age, your perception of South Los Angeles might have been formed by riots and rappers. Or maybe you know it through television — from “Moesha,” the Brandy Norwood sitcom set in Leimert Park, or “Insecure,” Issa Rae’s ode to neighborhoods such as Baldwin Hills, Exposition Park and Inglewood. But Gary Phillips, who grew up there, has a more historically complex point of view. His most recent mystery novel, “One-Shot Harry,” is based on Martin Luther King Jr.’s real-life visit to L.A. in 1963. For Phillips and the 13 other writers who contributed to his just-published anthology, “South Central Noir,” those narrower, pop-infused renditions are just the tip of the iceberg.

Recently I convened a Zoom panel with six of the book’s contributors — Phillips, Tananarive Due, Gar Anthony Haywood, Naomi Hirahara, Emory Holmes II and Roberto Lovato — to get a sense of how the project came together and how it helps fill in the portrait of this historically rich 33-square-mile region.

A couple of years ago Phillips sent Johnny Temple, publisher of Akashic Books, an email suggesting it was time for a “Noir” anthology set in South-Central. The small press’ award-winning series has covered the world in crime since 2004, but its 100-odd volumes primarily focus on cities — plus there were already two editions of “Los Angeles Noir” and books on Orange County and Palm Springs. But Phillips was thinking more specifically about his stamping grounds — especially its vivid history. “There was the death of soul singer Sam Cooke in 1964, which happened at a ‘hot sheet’ motel not far from where I grew up,” Phillips recalls, ticking off a few of the area’s dishiest real-life events before delving into its persistent issues, from police brutality to gentrification, and its continuing evolution.

Temple agreed a more hyperlocal anthology was a good idea. “The first ‘Los Angeles Noir’ was an L.A. Times bestseller and sold 25,000 [copies], which is highly unusual for an anthology,” he said in a recent phone call. And “South-Central has only grown in national and international importance” as racial justice has become a broader conversation.

History is a driving force in many of the resulting stories. “Though highly segregated in the 1920s and 1930s, Black Los Angeles was undergoing this wonderful renaissance,” Holmes says, “which included the establishment of the Dunbar Hotel. ... It was where people like Duke Ellington or W.E.B. DuBois could have a quality stay.” In this glamorous milieu, Holmes’ contribution, “The Golden Coffin,” turns on a fictional serial killer who preys on Black women and girls.

“Palm Springs Noir,” the latest story collection in Akashic Books’ “Noir” series, unleashes darkness, desert camp and ample blood in the pool water.

“Noir fiction is as much about place as anything,” says Holmes. “Just as Los Angeles became a character in Raymond Chandler’s fiction or San Francisco in Dashiell Hammett’s stories, South-Central L.A. became another character I had to develop in telling the story,” as important as the Dunbar bellboy at the center of his story.

The philosophy of place as character is a recurring theme in the collection — as it was during the panel. In “All That Glitters,” Haywood set himself the challenge of writing about Simon Rodia’s iconic Watts Towers.” “As I was growing up,” says Haywood, “whenever my father would take us for weekend drives, we’d end up at some iconic L.A. landmarks” — as you would if your father was architect Jack Haywood, co-designer of the California African American Museum.

“All That Glitters” is a tightly plotted story of familial greed that becomes the stuff of urban legend for a group of security guards at the towers — packing in the twists and misdirections that play out at greater length in Haywood’s Aaron Gunner mysteries. “It starts with the magic I feel for the place,” he says. “The Watts Towers are a fantastical construction that I think the young at heart would look at and think, ‘This is right out of a storybook.’”

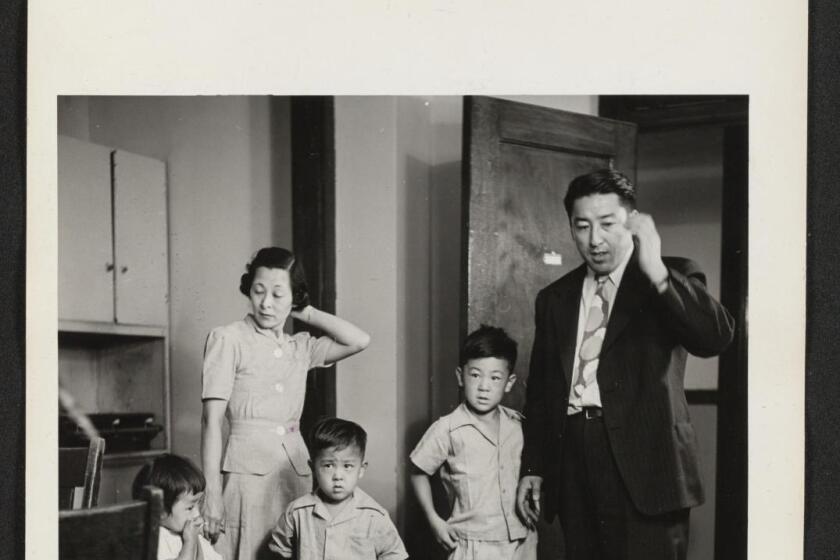

“I Am Yojimbo,” Hirahara’s take on South L.A. in the 1980s, recalls her days as a reporter and later editor of the Rafu Shimpo, the city’s Japanese American daily newspaper, and reflects the intersection of Japanese and Black cultures. “Even though I grew up in Pasadena,” she says, “I spent a lot of time around Crenshaw and Jefferson. I got my first car loan from the Japanese credit union that’s still in the area.”

Hirahara used the bygone Kokusai Theatre, beloved landmark for fans of classic Japanese cinema, as the principal setting of her story, which involves a teen-age, Japanese-culture-besotted Black usher at the theater. His discovery of a VHS tape brings him face to face with dangerous yakuza. Along the way, Hirahara namechecks Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a martial arts movie buff who patronized the Kokusai Theatre, as well as other cultural touchstones.

Naomi Hirahara’s “Clark and Division,” set in Chicago, shines a light on the little-known aftermath of internment. It’s a crime novel only she could have written.

Due, who also lives outside the neighborhood, tapped her memory of book signings at Eso Won Books to write her evocative story, “Haint in the Window.” “When Gary reached out to me, the first thing that hit me was Leimert Park,” Due says. “I was thinking about Eso Won, my bookstore, so I fictionalized it and filled with the ghosts of my past as a writer. It’s about a community that’s changing, but also a reading community that’s changing.”

Eso Won’s owners recently announced its impending closure. Due had already written her story, but a more general grief over places and people alike fed into to the horror-infused crime at its center. She even included a quote from the much-mourned science fiction writer Octavia Butler, which captures the story’s theme: “The only lasting truth is change.”

There is no stronger proof in the collection of that lasting truth than Lovato’s contribution. “Sabor a Mi” is set in a Salvadoran enclave in Slauson Park, where a war veteran-turned-PI, Rocky Anaya, investigates the murder of a neighborhood peacekeeper.

“L.A. taught me a lot about race relations,” Lovato says, “about globalization in cities, about politics, about something I call the Latino-Americanization of the United States.” This, he adds quickly, “has nothing to do with the demographics of the Latino population but with things like the division between the rich and the poor in the U.S. … and a policing model that is increasingly making obvious the terror component in law enforcement.”

“Sabor a Mi” draws on Anaya’s work as a counterintelligence officer in El Salvador’s FMLN, a background he shares with Lovato. The location of the killing also connects it to the Symbionese Liberation Army, the domestic terrorist group that kidnapped Patty Hearst in the 1970s — adding yet another layer of history to the map of South Los Angeles laid down by the contributors. (Others include Steph Cha, Jervey Tervalon and Penny Mickelbury.)

In “Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and Revolution in the Americas,” Roberto Lovato finally tells the full story of his rebel life.

In addition to editing “South Central Noir,” Phillips contributed a contemporary story, “Death of a Sideman,” in which two old friends survey the changing region: “The coming of a metro train signaled an uneasy development of the area. Riding in on those rails was gentrification, which also meant displacement.”

“We know that change is inevitable,” Phillips says, “yet here we are in 2022, and I wonder why we can’t improve yet keep the character of the neighborhoods and the people who live there intact. I know my job as a storyteller is to entertain, but invariably it comes up, since it’s part of the landscape. And, as a writer and an editor, you try to strike a balance, to ground your stories in a certain kind of reality.”

“South Central Noir” contains many realities. The panel of gathered writers was quick to rib Phillips for what Lovato called his “aggressive recruiting style.” But you could tell that they were glad for the invitation, with the result that their work — and their city — is much richer for the exercise.

Woods is a book critic, editor and author of the Charlotte Justice mysteries.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.