Review: ‘Severance’ author Ling Ma doubles down on surreal premises in ‘Bliss Montage’

On the Shelf

Bliss Montage: Stories

By Ling Ma

FSG: 240 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

One of my former editors once told me not to mention a book’s cover in a review — that it cheapened the words inside by tying them to the work of the publicity and marketing buzzards. I dissent.

In “Peking Duck,” one of the standout stories in Ling Ma’s collection, “Bliss Montage,” a young writer presents an early copy of her new book to her mother. It’s a story collection “with a vaguely Chinese cover image of persimmons in a Ming dynasty bowl.” The image implies tradition and delicacy, pretty stories of domestic imbalance and clichéd Eastern promises of good fortune. Ma tells us what it looks like because she knows it matters.

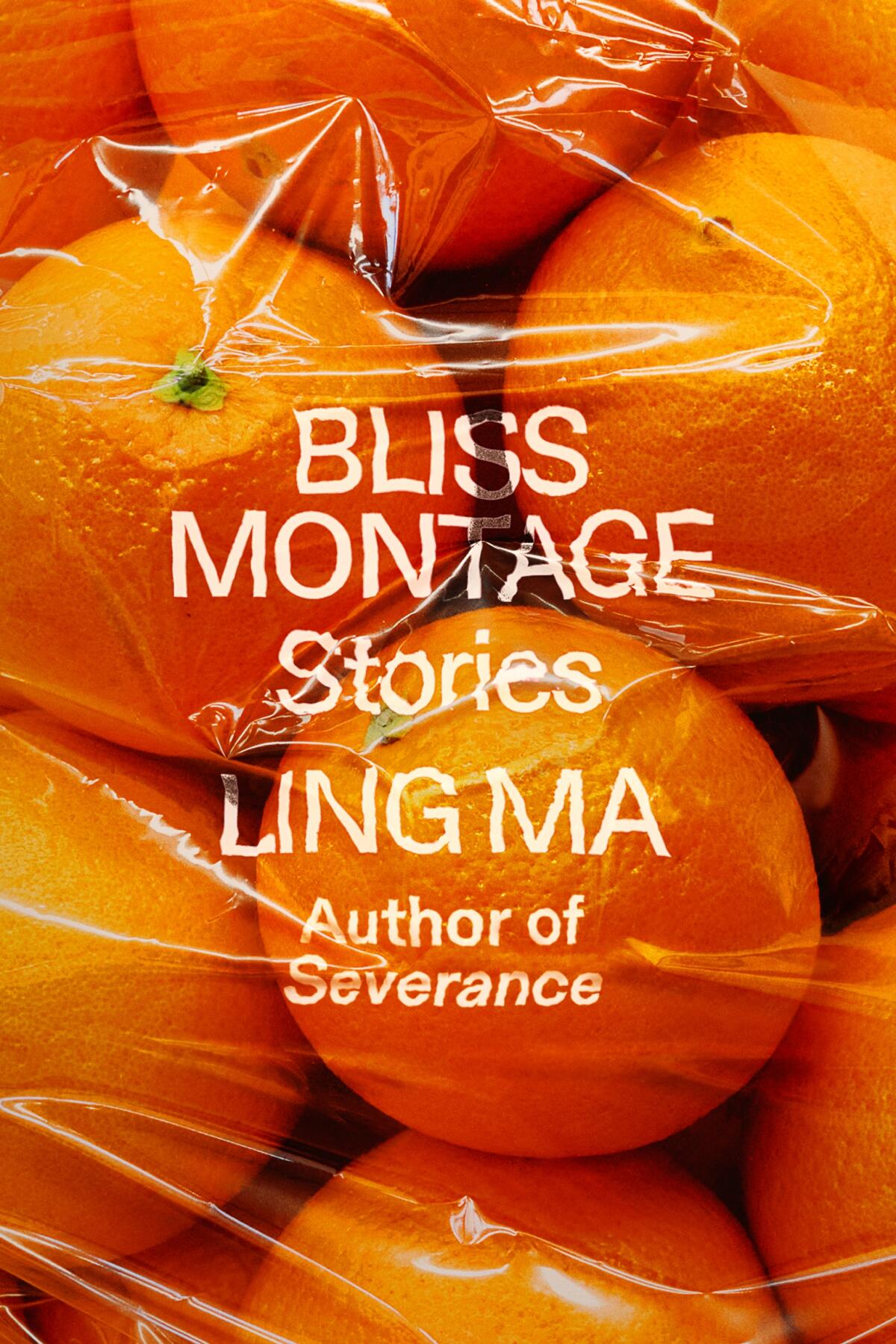

On the cover of “Bliss Montage,” clear plastic clings to the nubbled curves of oranges, suffocating all that sunshine-y zing. The title and Ma’s name are ruffled too, as if the author herself were shrink-wrapping delicious pleasure into a denatured product.

The stories of “Bliss Montage” keep the cover’s cheeky promise. They take place in little pockets removed from “real” life, whatever that means: inside a parallel world hidden behind a wardrobe; at a cultish festival in a fictional country; on a protracted vacation in a “de-Americanized” world; in an MFA workshop. The air has been sucked out of all these claustrophobic nowheres.

The pieces share a definite mood, and it’s lonely as hell. Characters float among chatting groups at parties without making a ripple. One woman awakens after a plane lands to discover that her husband has disembarked without her; it registers, but barely. When characters disappear in these liminal spaces — and quite a few do — it’s unclear whether anyone will ever notice.

After Ling Ma got laid off from her office job, she decided to get her revenge by killing almost everyone in the world — in her debut novel, that is.

This much feels familiar from Ma’s lauded comic-dystopian debut novel, 2018’s “Severance,” in which publishing drudge Candace keeps updating her photography blog, “NYGhost,” after (most of) the rest of the world has been infected by an unusual plague. Like all apocalypse Final Girls, she is somewhere she ought not be, in a nether region between humanity and whatever comes next. NYGhost can see but is never seen, both when her city is thronged and when it’s empty. “Severance” is a prototype for the best of “Bliss Montage”: surreal but rooted, watching at a remove while the world crumbles. Ghosts are the ultimate voyeurs — writers in their ectoplasmic state.

Ma rides a good concept when she finds one. After starting with two unfocused stories, the collection takes flight with “G,” about two women in a dissolving friendship who spend their last night living in the same city high on a drug that makes them invisible. The side effects remind us of other lettered drugs, including E and K: “You walk around with a lesser gravity, a low-helium balloon the day after a birthday party.” You shed weight via raging diarrhea — literal body loss. But you can also knock drinks off tables at sidewalk bistros or grope one another under cover of temporary irresponsibility. Before you swallow the seashell-shaped pill, you take off your makeup and strip naked; vulnerability is the gateway to freedom.

There’s a catch, though. “I have done so much G,” the unnamed protagonist relates, “that my adult sense of self formed in the complete absence of my reflection.” As a teenager, she was warned by her mother when she gained weight: “Those are my cheekbones. Don’t lose them.” But like it or not, a body is what tethers you to Earth, and when the cheekbones, along with the rest of her, disappear for more than a few hours, the unnamed woman panics from inside her new self-less-ness. Who are you if you cannot see who you are?

Bring up the bodies. Ma wants to see what they can do in fiction, aside from wreck our self-esteem. In “Returning,” a woman flies to her husband’s homeland, the tiny made-up nation of Garboza, and follows him into the forest, where citizens ceremoniously bury themselves overnight and hope for healing.

In Ma’s last story, “Tomorrow,” a sad bureaucrat in a future world where “the US was no longer number one” retreats to the country of her birth after a breakup and an unexpected pregnancy. The fetus inside Eve wants to assert itself too: Its arm emerges from between her legs early in the pregnancy and dangles there like, well, an appendage, and you know what I mean. (Sadly, Ma doesn’t explain how the sweet, chubby limb isn’t crushed when its mother takes a seat. As a twice-pregnant person, I need to know.)

Meghan O’Rourke’s ‘Invisible Kingdom’ expands from her own bouts of chronic illness to examine how it’s treated -- or not -- by our healthcare system.

The later stories in “Bliss Montage” grow more fluid, as if the earliest ones are vocal warmups and the last are performances at Carnegie Hall. But the entire collection might as well have been written for “Peking Duck” and “Office Hours,” two powerhouses so absorbing that you’ll pray Ma spins them off into future novels.

(There is also a middle story quite like this parenthetical: short, cleansing, unnecessary but invigorating, about a yeti wearing a human suit that brings a woman back to its apartment and turns her on to mythical-beast lovemaking, set to the smooth beats of Janet Jackson’s “Velvet Rope.”)

In “Office Hours,” a film studies professor on the brink of leaving academia discovers a doorway to a cool, dark forest behind an armoire. The Narnia allusions are in neon. But Ma isn’t content to lead Marie to a land of otherworldly delights. Marie teaches a course called the Disappearing Woman, but she cannot shake the men she wants to leave behind; even a C.S. Lewis knockoff fantasyland can’t maintain the “extreme, surreal privacy” she comes to cherish. Can’t a woman simply wander off into another universe? Or, as Ma slyly notes, has fiction pushed them out of the frame so many times that now it has to drag them back, kicking and screaming?

Sometimes women disappear inside their own writing, swallowed up by the cruel tricks fiction can play on its own author. “Peking Duck” is rooted in a paragraph-long Lydia Davis story about a writer whose “favorite story she has written” is one she has merely read, which relays a student saying his favorite memory was his wife’s memory of eating duck in Beijing.

Ma pulls at the flesh of this juicy morsel until it is so distorted that it can no longer safely hold the seed at its center. Working from Davis’ wicked game of narrative telephone, Ma nestles new stories inside each other — and then the littlest matryoshkas tear apart the bigger dolls in a futile quest to escape their form. Her version is wrapped in a story her protagonist tells of her immigrant mother, with “broken and halting” English, losing her job as nanny to a fancy white family. But that story is ripped apart too, first in an MFA workshop and then by her mother, and by the end we’re left wondering if Ma might regret this genius story too. “Look, we’re not like Americans,” the mother tells her daughter. “We don’t need to talk about everything that gives us a negative feeling.”

But the mother doesn’t control the narrative here. In fact, we don’t know exactly who does. Fiction, that slippery, transparent shrink-wrap of artifice pulled taut across reality, is running the show.

Bethanne Patrick’s September highlights include sequels from Elizabeth Strout and Andrew Sean Greer along with exciting debuts.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York Magazine, Vogue, the New York Times Book Review and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.