For one award-winning Black L.A. author, light skin was no refuge

On the Shelf

Light Skin Gone to Waste

By Toni Ann Johnson

University of Georgia: 232 pages, $23

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Maddie and Tobias have been inseparable since they were toddlers. But one day Tobias learns that Maddie, despite her light skin, is Black — although that’s not the word the little boy uses when he confronts her about her race.

For Maddie, one of the few Black children in Monroe, N.Y., in the 1960s, this is a startling moment, the one in which she suddenly, irrevocably, becomes an outsider. This heartbreaking scene occurs in “Claiming Tobias,” the second in a series of linked stories in Toni Ann Johnson’s taut and emotionally wrenching new short story collection, “Light Skin Gone to Waste.”

The pain of racism is only half of what young Maddie must endure. The balance is inflicted by her mother, Velma, a self-absorbed woman quick to lash out at her daughter verbally and physically, and by her equally selfish father, Phil, consumed with his relentless pursuit of white women.

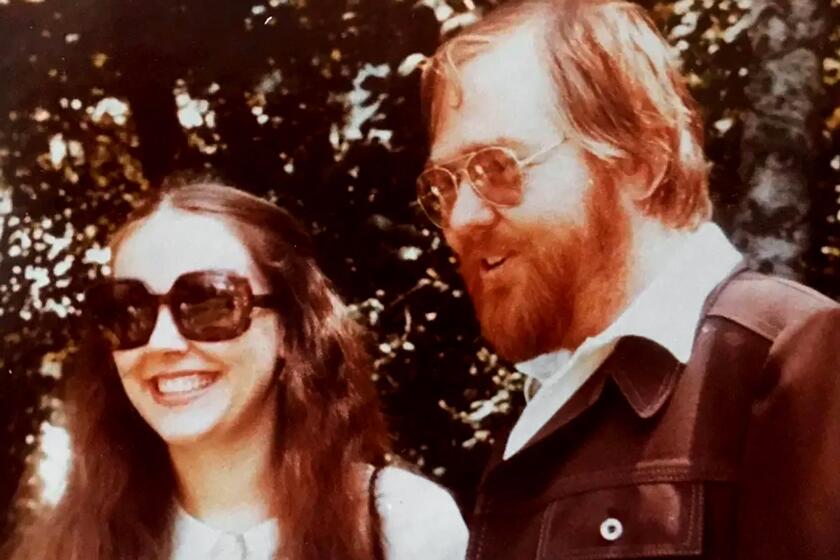

The author grew up in Monroe enduring similar torments and tribulations. While her stories humanize Phil and Velma by letting us see how they once suffered, she never lets them off the hook for their callous parenting.

Johnson, 59, is a Los Angeles-based playwright, screenwriter and author of several books. This collection, and its powerful reflection on identity and the accumulated impact of childhood wounds, found a publisher after winning last year’s Flannery O’Connor Award for short fiction. She spoke by video from her home about what it was like turning her childhood into fiction and whether it helped exorcise the pain. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Deesha Philyaw talks about the long gestation of her collection ‘The Secret Lives of Church Ladies,’ a Times Book Prize finalist for first fiction.

Phil, Velma and Maddie are shaped by issues surrounding race in America but also by their own personal histories. Are those two threads intertwined for you?

A lot of times when people write about Black characters it’s so much about race, and that minimizes the complexity of the full human being. But it all gets mixed together. Phil is shaped in large part by the loss of his father. One consequence is that he feels rejected and marginalized in the family by his mother. She articulates that this has to do with color — Phil is light and his brother, who is brown, gets treated better because she worries he will have a tougher time.

Velma was abandoned by her birth parents, but even that had to do with race because her birth father was white and presumably not single since her mother was working in his household. So she wasn’t a white baby — she wasn’t a wanted baby.

I felt Maddie’s life was made difficult as much by what she experienced with regard to race as by questionable parenting.

How much of Maddie’s experience is based on yours?

I didn’t have a very sophisticated awareness of it as a girl. All I knew was what was in front of me. I felt isolated even when I was little. The first wound was that neighbor across the street. I knew from then on that I had to be on guard for people who didn’t like me because I was different. That happened in Girl Scouts. But even though there were kids who didn’t like me or whose parents didn’t want them to play with me, I always had friends.

I became more conscious of it in middle school when I wanted attention from boys, and I’d go visit family in Harlem and Queens and Long Island. And there were boys who actually thought I was cute. I got more angry as I got older. In my late teens and early 20s I saw there were middle-class Black communities we could have lived in, and I was furious. I had thought we were an anomaly, and we weren’t.

Has living in Los Angeles changed you as a writer?

I’ve been here 30 years, so I guess I’m from here now. I bought a house in 2003 in a Black working- to middle-class neighborhood in South L.A. It’s so different from where I grew up. This community did change me as a human being and did change the writing.

Your novel, “Remedy for a Broken Angel,” and novella, “Homegoing” (about an older Maddie and Velma), also feature difficult mothers.

It comes out in everything. If you look at this book, all the mothers are narcissists, not just Maddie’s. That’s what I associate with mothers, that’s what I know.

Erin Keane’s mother ran away from home at 13 and married two years later. In “Runaway,” Keane unearths her parents’ past and the myths that shaped them.

Did you think about redeeming Phil and Velma at all?

They are softened for the book. That’s the sad thing. [Laughs] I had fewer nice or kind moments. I thought Velma is sort of redeemed as much as a person on the narcissistic spectrum can be. There was no time when my father noticed I was sick or depressed and took me to a doctor. But the character is a psychologist, and a normal psychologist would recognize that their kid is behaving differently. My father was off playing tennis, he wasn’t checking on what was wrong with me. So that was as much redemption as I could give Phil.

I tried to make them more entertaining than my actual parents and the dialogue more fun, because my mother speaks in clichés.

Did you, like Maddie, have an encounter as an adult with your childhood bully? Could you forgive him?

I did encounter one on Facebook. That person is a Trump supporter and bashing Black Lives Matter. I don’t forgive that because it affected my self-esteem and personality and shaped who I became. But I don’t hold on to the hatred or anger. I’m no longer affected by that emotion. I could forgive if I received an actual and sincere apology. Otherwise, why do I need to forgive someone who threw rocks at me and called me the N-word?

Do you feel, finally, that you’ve exorcised some of your pain by telling the story head-on?

It was cathartic getting the whole story with Tobias down and coming to terms with that whole arc. But it was painful at different times. I still have residual pain about my mother slapping me. The last time she assaulted me I was 17. As a child, I did not know it was wrong for parents to hit children — I thought I was being punished because I was a bad girl and deserved it.

Throughout my life, I’ve been told that what I experienced wasn’t that bad and that I was lucky to have the childhood I had. There was no empathy from my family. Writing about my memories and looking closely and carefully at those events helped me process what happened in a way that I hadn’t previously. Sharing the story with readers has allowed the kid in me to feel acknowledged. That’s healing — being heard is a relief.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.