Sam Lipsyte’s new ’90s caper novel is a glorious, grungy Gen-X swan song

Review

No One Left to Come Looking for You

By Sam Lipsyte

Simon & Schuster: 224 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Among the takeaways from 2022 is the feeling that everything was better in the 1990s. It’s not only grizzled Gen Xers tolling the bells for lost youth as they enter their pensioner years. Millennials too are wondering about regional music scenes and Rock the Vote and asking why we can’t return to the era of our childhood, when history was over, irony was in, social media hadn’t yet ruined everything and we could chug our Zima and dress like half-assed lumberjacks in peace.

In “No One Left to Come Looking for You,” novelist Sam Lipsyte has chosen a key hinge moment in the mythos of that decade’s anti-pop pop culture: the post-“Nevermind” comedown, after Nirvana’s 1991 album had sold kajillions and it seemed a new generation of punk-lite kiddie bands incubated in A&R meetings was going to supplant all things pure and virtuous (I’m looking at you, Silverchair). Or at least it seemed that way for those hardy and very broke musicians who carried the tattered flag for the halcyon days of Gang of Four and the Fall. True believers like Jonathan Liptak, a.k.a. Jack S—, the charmingly naive, fiercely committed amateur at the center of Lipstye’s savagely funny and sharply observed fifth novel.

Ever since Lipsyte emerged in 2000 with his short-story collection “Venus Drive,” he has been preoccupied with characters searching for some kind of twisted honor in resisting the money- and status-obsessed modern world. It tends not to work out for them; Lipsyte’s humor is born of their impotent rage against the machinations of runaway capitalism and unchecked acquisitiveness.

Like Lewis Miner, the antihero of Lipsyte’s 2005 novel “Home Land,” Jack tries to find himself by opting out. A suburban exile, he is determined to take a stab at anti-establishment glory with his near-good and rarely great band, the S—s. Jack has decamped to Manhattan from the cultural swamp lands of New Jersey at a time when many of the graffiti-splashed monuments to the city’s musical past have been plowed under for condominiums and office monoliths. This devolution is due in no small part to developers like the young-ish Donald Trump, who figures in Lipstye’s plot as a malevolent off-screen presence.

Greg Ginn started a record label that brought the world Sonic Youth, Hüsker Dü, the Minutemen and more. A photo book and a deep history tell his tale.

Yet at the start of the decade, downtown Manhattan (Brooklyn hadn’t yet entered the chat) still had room for a “dark, quasi-cheerful scuzz parlor” like the Stop Pit, where Jack and his buddies take shelter under the distempered glow of motorcycle logos, or King Snake Guitars, where it is verboten to use classic rock clichés like “chops or axe or jam.” Lipsyte knows that all punk rockers are reverse snobs, who decry conservatory-trained musicians as “smug skill-bullies” and bark sloppy, shambolic rants against … well, even Jack himself isn’t sure, as “irony smothers our politics.”

But then Jack’s bass is filched from his apartment, and his charismatic junkie lead singer, the Banished Earl, vanishes along with it. Could the disappearances be connected? Thus begins Jack’s odyssey through the last vestiges of New York’s scabby demimonde — the dives and drug corridors where he might find what he’s lost. The great drummer Hera has left his band for a “self-regarding minimalist duo” called Thorazine, but she agrees to play one final show — if the Earl, her ex, manages to turn up. Jack is on a mission to save his friend and perhaps himself.

“No One Left” is designed as a caper, a kind of “lost on the Lower East Side” picaresque that will remind some readers (I’m looking at you, boomer) of seminal downtown New York films like Martin Scorsese’s “After Hours” and Jim Jarmusch’s “Permanent Vacation.” More than anything, it’s a tender valentine to an era when the idea of ditching the Man for a life on the margins could keep you insulated from adulthood for as long as you could possibly hold out.

Like all the other faux Joe Strummers in town, Jack hopes to act the part of an insurrectionist at a time and place when self-creation on $5 a week feels achievable. There is also the constant fear of selling out — back when that was a thing — but as Jack points out, all bands think other bands are sellouts, thus behaving “like Russian nesting dolls of impotent rage and insecurity.”

While on the hunt, Jack finds himself barking up the wrong trees, sniffing out trails that go cold. Along the way to the story’s open-hearted conclusion, Lipsyte introduces us to a rogue’s gallery of art-damaged misfits, biker bruisers, crooked cops, earnest but incoherent performance artists — in short, the kind of folks you don’t see in SoHo much anymore. Lipstye clearly knows this universe from the inside out; his characters are charmingly naive, self-conscious dreamers, their heads full of Marxist critical theory, their art a bulwark against the creeping banality of modern life.

Dan Ozzi’s ‘Sellout: The Major-Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore’ tracks the fortunes of Jawbreaker, Jimmy Eat World and others.

The author has a gift for set pieces that flesh out his nostalgic world-building. To cite just one example, there is the alluring mystery girl Corrina, who wears “a crinkly polyester nurse’s uniform” and recruits Jack to participate in her performance piece about the medieval nun Hildegard of Bingen by having him dress up like a character from the ’70s sitcom “Three’s Company” drenched in menstrual blood. Her moral convictions are as intoxicating as her artistic vision is blurry. Jack is hooked.

“No One Left” is that rare thing: a satiric crime novel that doesn’t forsake story for style. It is tightly plotted and pleasingly twisty. Jack stumbles upon information he shouldn’t know, and when another ex-band mate is killed, he stumbles into the crosshairs of Heidegger Mounce, a thuggish minion of a certain future U.S. president trying to avoid paying his construction bills.

To reveal the satisfying resolution would be a crime in itself; suffice it to say that Lipstye locates the moral rot of today’s island of the 1% in the unchecked greed of real estate panjandrums hellbent on choking the life force out of a once-great city. And yet Jack is unfazed; by the end of the book, he remains convinced that the world can still be saved by a great 20-minute set of teeth-gnashing, anticorporate punk rock. There’s just the small matter of getting the world to listen.

Even if you weren’t there — and how many of us really were, after all? — Lipsyte’s novel is a fitting tribute to a time when, as Jack reflects, “The cacophony [sounded] just right, or even goddamn glorious, the sadness of its passing built right into the peak. Like everything good, I guess.”

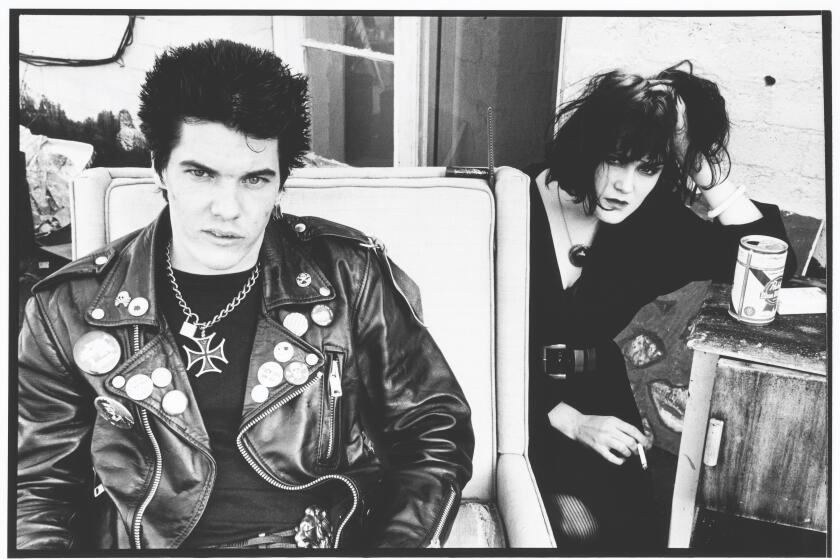

Melanie Nissen was there at the creation of L.A. punk and has the pictures to prove it. She talks about “Hard+Fast,” a new collection of her photos.

Weingarten is a writer in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.