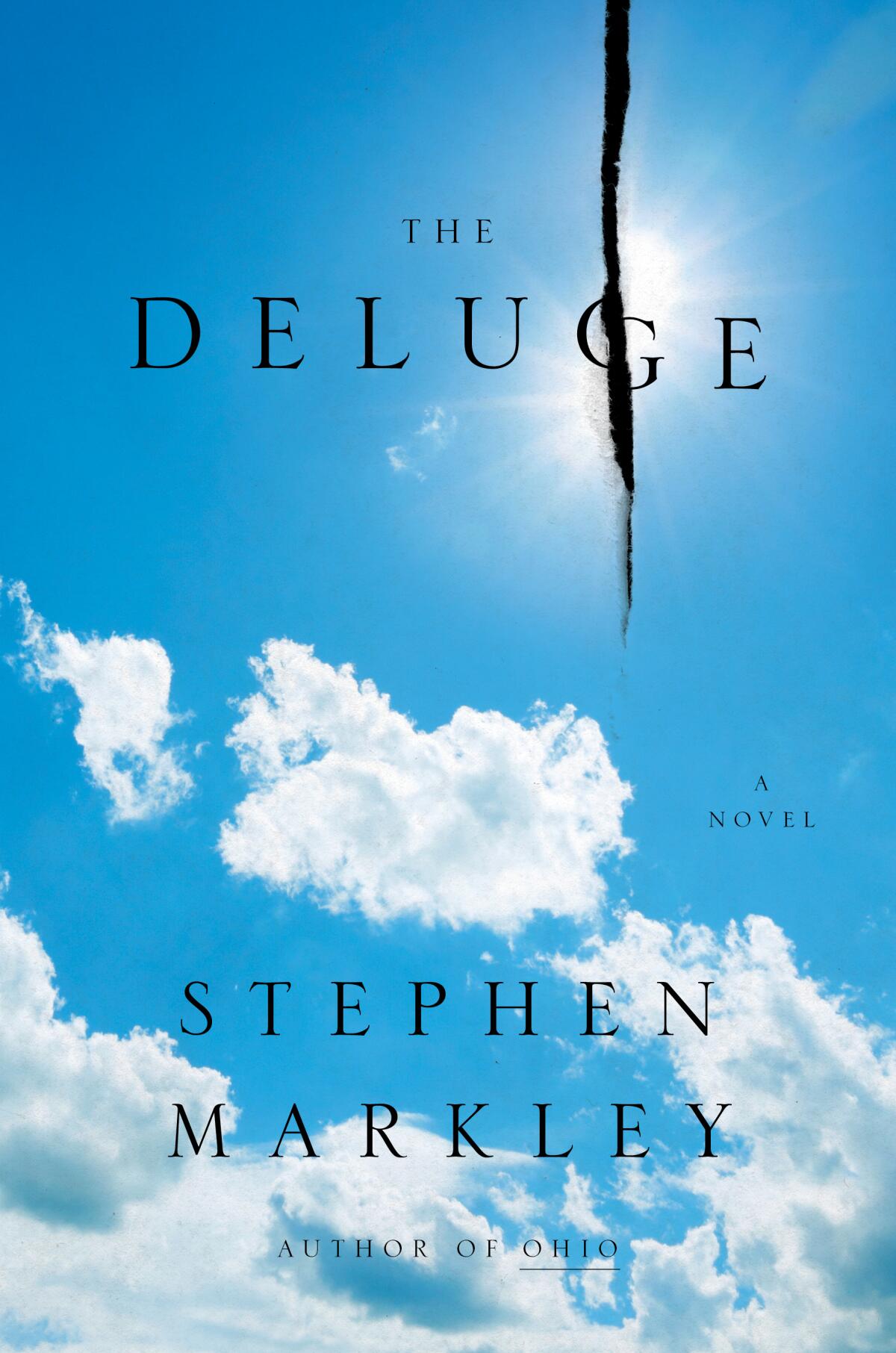

‘The Deluge,’ an epic new climate novel, drowns us in catastrophes

Review

The Deluge

By Stephen Markley

Simon & Schuster: 896 pages, $33

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Although there are dozens of characters populating Stephen Markley’s second novel, “The Deluge,” the real protagonist is America, and although numerous forces and foot soldiers undergird the story’s antagonist, the true villain is climate change. This is an accomplishment — in the way, for example, a city can be the best kind of character — but it also detracts from the novel’s humanity, as the people animating it are secondary to the concepts.

Over nearly 900 pages, Markley moves methodically from 2013 to the 2040s, presenting a kaleidoscopic sampling of American citizenry, an unrelenting series of increasingly tragic events and an in-depth examination of the desperate corner into which the world has painted itself. It is, if nothing else, an astonishing feat of procedural imagination, narrative construction and scientific acumen.

Markley is an immensely gifted novelist, but he set himself a nearly impossible task, which appears to be his MO. His first book, the memoir “Publish This Book,” stemmed from Markley’s frustrations trying to sell a novel. It’s a meta-memoir in the vein of Dave Eggers or Chuck Klosterman, and though it’s funny and clever at times, the conceit wears thin after almost 500 pages. His debut novel, “Ohio,” took on a heavy subject (the opioid crisis), a large cast and a complex structure and ended up suffering from the same issues as its successor: characters subservient to theme. The redeeming merits of “The Deluge” call to mind those elaborate trick shot videos on social media in which the primary objective is missed but something else exciting occurs; these are always captioned by the phrase “failed successfully.”

Lydia Millet, whose latest novel, “A Children’s Bible,” tackled climate change, reads new fiction on climate and argues against calling it a genre.

The plot involves — are you ready? — a scientist named Tony Pietrus whose book on undersea methane functions as the novel’s core text; an activist named Kate Morris who makes headway toward combating ecological disaster by dint of undeniable magnetism and political savvy; Ashir al-Hasan, a genius in predictive analytics who turns his intellect from sports betting toward the future of Earth’s habitability; a once-famous actor who transitions into an ultra-right wing zealot under the moniker The Pastor; an advertising executive who helps orchestrate the oil industry’s response to fossil-fuel opposition; a recovering drug addict in rural Ohio who ends up an unwitting pawn in the climate war; and the enigmatic leader of a hardcore eco-terror outfit called 6Degrees. Orbiting these characters is an enormous supporting cast of allies, enemies and sycophants, including numerous real-life figures ranging from Barack Obama to Anders Breivik, the Norwegian mass murderer.

As the weather grows increasingly hostile and resources become scarcer, the reality of climate change forces action but, predictably, capitalistic short-sightedness and political maneuvering stifle any progress. Employing numerous narrative techniques — first-, second- and third-person points of view; news articles, interview transcripts, journals, et al. — Markley traces the development of complex (but ultimately ineffective) legislation, the behind-the-scenes negotiations of multiple presidential elections and the logistical nightmares created by the destruction of the environment.

Floods wipe out entire cities, fires blaze through hundreds of thousands of acres of land, food shortages affect millions, heat waves kill and hurricanes redraw the American coastlines. And that’s just the weather. Multiple characters are savagely tortured and murdered while many more, including a child, are assassinated. The U.S. government ends a nonviolent siege of the Capitol by plowing down hundreds of protesters in a cascade of bullets. Suicides, self-sacrifices and illegal imprisonment abound.

The author’s 12th novel, ‘Stella Maris,’ publishes on Tuesday. It’s high time for a complete reader’s guide to the Western novelist, from ‘The Crossing’ to ‘The Passenger.’

Climate fiction tends to take place either in an already-decimated future — dystopias like Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” or Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road” — or in the prickly present, the dire era of inaction featured in Richard Powers’ “The Overstory” or Ian McEwan’s “Solar.” “The Deluge” dares to imagine, painstakingly, how we might get from here to there, filling a giant canvas with Brueghelian detail that, while making the story compelling, also flattens some of the emotional impact. Characters disappear for as many as a hundred pages and reemerge a year later, necessitating repeated exposition dumps. As a result, the reader doesn’t feel intimately close to most of the characters.

The central figure, Kate Morris, is observed exclusively through the eyes of others, never narrating her own experience. She’s a study character, like Gatsby, whom everyone comments on but no one truly knows. Moreover, nobody in “The Deluge” changes in the conventional sense. If anything, they dig deeper into themselves. Tony Pietrus, the climate scientist, is as stubbornly steadfast and gruff by the end as he is when we first met him.

When climate change is the subject of fiction, it becomes easy to interpret as advocacy, as a political novel of ideas rather than a tale driven by characters. Markley does little to dispel this impression. When there is yet another extreme weather event in “The Deluge” and many people lose their homes, communities and lives, it’s hard not to feel a bit bludgeoned by it all. There are moments when his detailed enumeration of geographic calamities reads like David Wallace-Wells’ “The Uninhabitable Earth,” while some of the procedural stuff comes across like a forward-projected version of Nathaniel Rich’s “Losing Earth.” Both those books are nonfiction, which Markley takes great pains to mimic. This borrowed cloak of newsiness reduces the complexity of fiction into a single-minded polemic. Each storm, each wildfire, each avoidable death becomes a rehash of the same warning: This is what will happen if we don’t act now. Repeated finger-wagging, even the most deftly and eloquently crafted, grates after almost 900 pages.

An investor and tech futurist thinks the metaverse will revolutionize everything. That includes Disney and the rest of entertainment.

Markley does throw some satire into America’s next few decades, mostly in the form of VR environments called “worldes” that are like the metaverse’s wet dream, but he remains decidedly earnest about his vision of the future and his plea to our present. “One day,” Morris says in a flashback, “an awful lot of people are going to wake up, look around, and wish they’d done something when they had the chance.” Pietrus’ book is titled “One Last Chance.” Markley ultimately wants to express hope that humanity can come together to address the crises, but those moments are sparse and often yield very little, whereas his relentless saga of horrors is more dispiriting than galvanizing.

Clark is the author of “An Oasis of Horror in a Desert of Boredom” and “Skateboard.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.