A hardcore coming-of-age novel nails the glitter and grime of L.A.’s ’80s metal scene

Review

Gone to the Wolves

By John Wray

FSG: 400 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There is a direct relationship between the amount of crap you take for the music you love and the depth of your devotion to it. This is why headbangers and punks are the most loyal fans on the planet. Enduring everything from insults to parking lot beat-downs, devotees of extreme music earn their fandom.

This is certainly the case for the three main characters in “Gone to the Wolves,” an outstanding new novel by John Wray set in the world of ’80s heavy metal. Wray is the acclaimed author of five previous novels, ranging from the voice-driven (“Lowboy”) to the historical (“The Right Hand of Sleep”) and the experimental (“The Lost Time Accidents”). In his latest outing, he has nailed his milieu.

Christopher “Kip” Norvald is the proverbial new kid in town, who moves to Venice, Fla., to live with his grandmother and finish high school. His arrival is attended by a raft of rumors about his incarcerated father and drug-addicted mother, as well as his own involuntary stay in a mental health facility. These rumors are bolstered by Kip’s proclivity for slipping into a violent fugue-like state he calls the White Room whenever he’s threatened or stressed.

Greg Ginn started a record label that brought the world Sonic Youth, Hüsker Dü, the Minutemen and more. A photo book and a deep history tell his tale.

Kip is indoctrinated into heavy metal by Leslie Aaron Vogler, a.k.a. Leslie Z, “who had three strikes against him already: he was Black, he was bi, and he liked Hanoi Rocks.” Leslie is the scene’s savant and proselytizer. “It’s more than just a sound, of course. It’s more than an aesthetic,” he says. “It’s the road less taken, Norvald. It’s the … left-hand path. It’s a complete shadow culture, with its own laws, its own myths, its own scripture.”

The group is rounded out by Kira Carson, who is drawn to the most intense music she can find in a desperate search for truth: “Kira was the genuine article, a metal mujahid, a wild-eyed true believer, and the scorn she felt for music — for anything, really — that was soft or safe or tentative was too ferocious to resist.”

Naturally, Kip falls head over heels in love with her.

Wray’s story begins in 1987 with the emergence of a band called Death, whose record “Scream Bloody Gore” many consider to be the birth of death metal, a faster and more ferocious style stripped of ornament and played at punishing volumes.

Death was the brainchild of Chuck Schuldiner, who played all the instruments on the record save drums. Because Chuck’s mom goes to church in Venice, these misfits claim him as their own.

Venice was also the winter headquarters of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, and Kira is reputedly related to Grady Stiles, who performed under the name Lobster Boy and left behind a legacy of violence that Wray weaves into “Gone to the Wolves.”

After surviving high school, the trio moves to Hollywood, where Leslie and Kira fixate on a terrible glam metal band that keeps changing its name. Leslie’s motives are carnal, but Kira’s are harder for Kip to decipher.

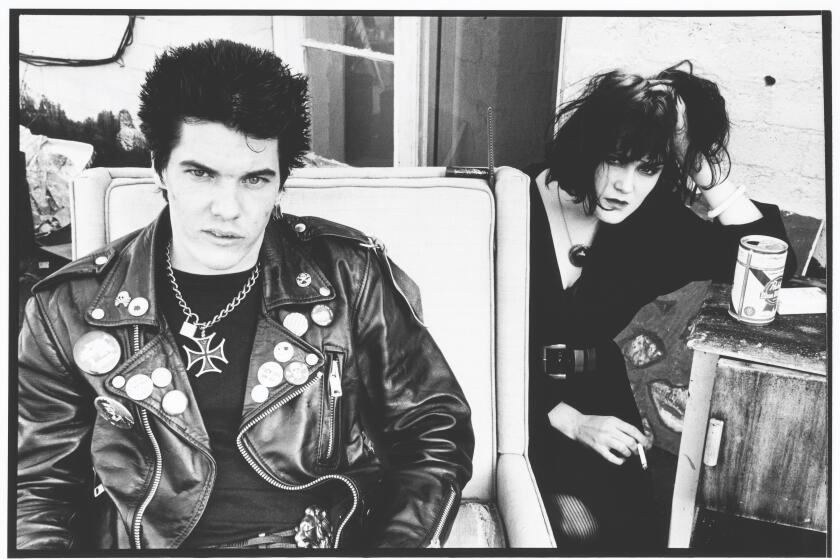

Melanie Nissen was there at the creation of L.A. punk and has the pictures to prove it. She talks about “Hard+Fast,” a new collection of her photos.

Kip’s musical taste is defined by what he doesn’t like, and as he reinvents himself as a reviewer for a zine called Hair of the Serpent, he discovers plenty to dislike in the druggy lore of the Sunset Strip.

“He couldn’t shake the feeling,” Wray writes, “that all it would take to bring the whole scene crashing down would be for someone, just one random person, to look around and start laughing.” (Though the band isn’t named, that’s the effect Nirvana had when it broke out in 1991 and sent hair metal back to the underground.)

Kip’s takedowns of the pay-to-play fame seekers who cavort about the Whisky a Go Go’s stage on weekday nights to half-empty rooms with glitter cannons and paisley scarves, are scabrous enough to give the likes of Lester Bangs and Kickboy Face pause.

Metal is not a cult or an ideological system but a scene, and a scene is always a cultural backwater of the mainstream. Kip, Leslie and Kira know how to survive a backwater. That’s one of the more hopeful messages encoded in “Gone to the Wolves”: If you can get through your childhood, you can make it through anything.

By refusing to imbue the shenanigans of the Sunset Strip with the banal glamour of MTV, Wray correctly presents it as a cultural morass even less enlightened than the Youth Center parking lot in Venice, Fla.

In the bathroom of the Rainbow Room, where Kira works, Kip addresses the semi-comatose singer for Mötley Crüe: “Wake up, Vince. This is your conscience speaking.” He proceeds to shred Vince as “an embarrassment to yourself and to your family. You spend more time on your bangs than you do on your songs.” He ends his diatribe by telling Vince “a storm is coming” — but fails to heed his own warning.

Kip embraces Kira’s notion that metal is a tool for excavating truth, and his truth is the White Room, an urge for violence that is part fatal flaw, part transcendental calling. Its repercussions push the trio to Northern Europe, where Kira finds herself in genuine peril and the novel swerves from a coming-of-age story into a freaky-deaky horror show.

“Chronology is an illusion, if not a deliberate lie,” a character posits in “The Lost Time Accidents,” the fourth offering from novelist John Wray.

To love music is to be on intimate terms with a magical revolving door. Sometimes you enter a piece of music; sometimes it enters you. To enter extreme music is to go to a place beyond melody or rhythm or even narrative, a place that leads to the darkness within the listener. The concept of exorcism is often associated with heavy metal, but ultimately metal is where you go to meet your demons, not purge them. Wray knows his stuff, and he masterfully sets the table, allowing Kira to pursue her own darkness and confront it where it lives.

Wray chooses not to describe the damage at the root of Kira’s trauma. The fact that the horror embedded in songs by bands like Morbid Angel, Deicide and Cannibal Corpse doesn’t come close to what’s at the core of Kira’s truth tells us it’s likely more than we — or anyone — should be asked to bear.

The one album Kip, Leslie and Kira can agree on is Metallica’s “Ride the Lightning,” a monument of thrash that captures the animus of punk and the theatricality of metal without getting too grandiose. While the lyrics to the band’s latest single, “Lux Aeterna,” sound like they were written by an AI chatbot, there’s an epic quality to Leslie quoting the chorus to “Fight Fire With Fire” that headbangers of every age will find thrilling.

Even if you didn’t spend your adolescence puking on your shoes in parking lots, flirting with calamity as distorted riffs thunder out of blown-out speakers or shutting your eyes while driving down the highway as you crank up to “Fade to Black,” “Gone to the Wolves” captures the feeling of loving something so intensely it just might kill you.

Ruland’s new novel, “Make It Stop,” is out now.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.