Fall Preview Books

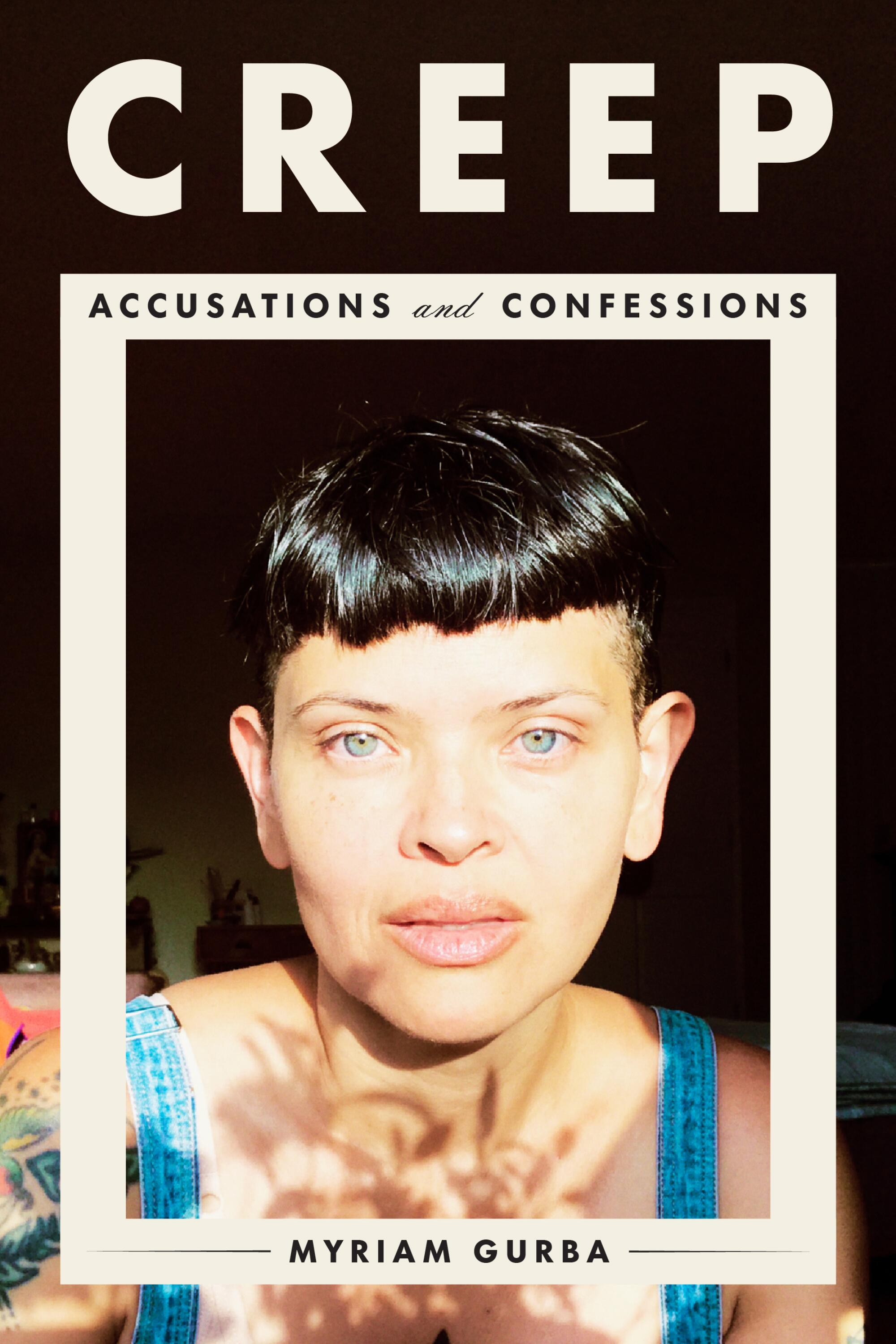

Creep: Accusations and Confessions

By Myriam Gurba

Avid Reader Press: 352 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Of all the weather phenomena, fog may be the richest in literary associations. To be in a fog is to have senses dimmed, to feel as if you’re inhabiting a space between worlds. For early 20th century Spanish Modernist Miguel de Unamuno — who wrote an entire experimental narrative titled “Fog” (sometimes translated as “Mist”) — it referred to the minutiae that obscure existence; in Ken Kesey‘s 1962 novel, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” it is the haze of hallucination.

For Myriam Gurba, fog is a condition that disorients and ensnares.

Born and raised in Santa Maria, the author grew up with the cotton-colored marine layer that regularly envelops the California coast. In the title essay of her forthcoming nonfiction collection, “Creep: Accusations and Confessions,” out next week, Gurba explains that she has long been captivated by fog. “The white floated like miles of strange breath exiled from its source,” she writes. “It embodied gothic verbs. It oozed. Crept. Snaked. Snuck. Its moisture tickled and licked, droplets settling on eyebrows, eyelashes, bangs and sage. The inscrutability of the white’s shape and size teased. Intangible, the soup was potentially infinite.”

This physical fog is accompanied by a psychological version: a relationship with an attentive suitor she calls “Q” who soon becomes abusive, holding her captive through violence and its constant threat.

“Creep,” like much of Gurba’s work, is less linear narrative than a constellation of topics that orbit one another: control, violence, isolation and defiance, with detours into Shakespeare, the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings and the nature of terroir. Binding these themes together are the suspenseful conventions of horror writing. (I found myself holding my breath in parts.)

And, of course, there is fog: soft yet sinister, intangible yet deadly. Fog, she tells me when we meet, is a “great metaphor” for domestic violence. “How can you be killed by love?”

…

You may have heard of Gurba, but it’s unlikely that you know her; her reputation comes swathed in some fog of its own. Gurba, 46, has published five books and too many short stories and essays to count. But the L.A.-based writer is perhaps most familiar for her famous takedown of Jeanine Cummins’ border thriller, “American Dirt,” in the online journal Tropics of Meta in 2019.

That searing piece, arguing that the novel “aspires to be Día de los Muertos, but it, instead, embodies Halloween,” ignited furor and then reckoning over representation and systemic racism in the book industry. In response, Gurba and fellow writers David Bowles and Roberto Lovato launched the group #DignidadLiteraria to advocate for a greater Latinx presence in publishing — an effort that led to a not-inconsequential meeting with honchos at Macmillan, the conglomerate behind “American Dirt.”

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in March of 2020 put those efforts into hibernation. (Though the uprisings that followed the murder of George Floyd three months later made the discussions of representation feel prescient.) Yet the controversy had the effect of typecasting Gurba as the impudent indie writer willing to torch the publishing industry to make a point about diversity. (Never mind that “American Dirt” went on to be a massive bestseller.)

That controversy spilled into another, when in February 2020 Gurba was put on administrative leave from her job as a high school teacher in Long Beach after she spoke out in support of students who had alleged abuse against a fellow teacher. She also raised public allegations against Q, the man she writes about in “Creep,” who worked for the district.

Seated at a sidewalk cafe on a bright L.A. morning, Gurba declines to discuss her departure from the Long Beach Unified School District. (She is no longer employed there.) Nor does she want to reveal any specifics about where she currently lives or works. But when it comes to her writing, she is far more open and revealing.

Jeanine Cummins’ novel about a migrant family, “American Dirt,” hasn’t been published yet but has already stirred a debate: Who should tell what stories?

To this day, she remains surprised by the reaction to her piece about Cummins. “It was shocking to me that that essay was as widely read as it was,” she says. “Certain critics and pundits and public intellectuals ascribed an extraordinary amount of power to me, alleging that I had permanently upset the publishing industry in these horrific, anti-white ways” — the final clause delivered with evident irony.

But she is ready to move on. “One of the things that really bugs me about some folks and their response to my work is that they will hyper-focus on that essay,” she says, “and completely ignore all of the work I do around gender-based violence.”

And, frankly, Gurba’s other work is more compelling.

“Creep” marks the follow-up to her critically acclaimed 2017 memoir, “Mean,” the intertwining tale of a sexual assault she survived at the age of 19 combined with the story of another woman, raped by the same man, who did not live to tell the tale.

“Mean” was part ghost story, part queer Chicana coming-of-age memoir. (Prior to her relationship with Q, Gurba was married to a woman for 16 years.) The book was also about narrative itself, challenging the ways women are expected to write about themselves and about sensitive subjects like rape. Rich with black humor, “Mean” never betrayed a lick of sentimentality. “I want to be a likable female narrator,” she wrote in that book. “But I also enjoy being mean.”

Poet and essayist Raquel Gutiérrez, author of the collection “Brown Neon,” says she sees Gurba in the orbit of feminists such as Virginie Despentes and Inga Muscio (the latter also hails from Santa Maria) — writers who address female sexuality and abuse in blunt ways. “It’s very punk rock,” she says of Gurba. “No tiene pelos en la lengua.” This is Spanish for: She does not mince words.

In person, Gurba does little to dispel her reputation for fearlessness. She says she has been scolded for using humor to address rape, the implication being that it’s disrespectful. “To that I always answer: I think rape is more disrespectful.”

‘She could count on the strip mall for highly effective magic. She parked in the lot’s only vacant spot, and before walking into the mall’s most brightly lit business, Silly’s Smoke Shop, she got a funny feeling and stopped’

She also comes off as sharp and considered — preoccupied, for example, by the oral traditions of her family, some of whom hailed from rural Indigenous communities around Guadalajara. “There is so much involved in the breath and the tone and the inflection that I think can be translated to the page, but it takes a lot of effort,” she explains. “For me storytelling is inextricable with orality. ... I read all of my work aloud until I get a rhythm, I think about that almost as a musical composition.”

…

The new collection is consistent with Gurba’s other writing in style and voice, but it is a very different work.

Where “Mean” was taut, “Creep” is longer and shaggier: a collection of 11 essays — some previously published — that explore a range of themes, many revolving around misogyny and violence. Included in the mix is the essay about “American Dirt.”

But the most absorbing pieces are those in which Gurba turns her unblinking gaze to life’s cruelties, weaving together disparate threads that somehow hold in the end.

In “Tell,” observations about the feral games children play — like tossing Barbies out of windows to their “death” — evolve into a rumination on how these games function as rehearsals for facing mortality as an adult. Gurba cites occasions when such games have turned literal. In a chilling incident from 1951, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, the future Mexican president, then only 3, had a hand in killing a housekeeper while playing war games with his brother. (The boys were fooling around with a loaded rifle their father had left in a closet.) Games about war, like war itself, can lead to death — no rehearsal needed.

Gurba has been scolded for using humor to address rape, the implication being that it’s disrespectful. “To that I always answer: I think rape is more disrespectful.”

Essays in “Creep” bounce between the power dynamics of practical jokes and sexual assault; between Franz Kafka‘s “The Metamorphosis” and the way Mexicans have historically been treated at the U.S. border. Many of the pieces, like “Mean” before it, also hopscotch through time — something Gurba attributes in part to close readings of Mexican writer Juan Rulfo‘s “Pedro Páramo,” the 1955 novel that helped kick off the Latin American literary boom of the 20th century.

In that masterful story, a man journeys to a village of the dead. “‘Pedro Páramo’ really scoffs at time,” says Gurba. “[It] is such a a challenging book because of the relationship to time, because life and death are happening simultaneously. I wanted to mirror that seeming lack of structure in my work as an homage to him.”

Rulfo materializes at the heart of one of the more pleasurable stories in “Creep,” an essay that revolves around Gurba’s larger-than-life (and quite sexist) maternal grandfather, Ricardo Serrano Ríos, a Guadalajara publicist who had been a friend of Rulfo’s in school. Serrano spent his life alleging that he’d given Rulfo a manuscript of his poetry that was never returned — and that Rulfo had pillaged it for ideas.

“The other way Juan had supposedly ripped off Abuelito was by selling him an incomplete set of encyclopedias for two hundred pesos,” writes Gurba. “He still carried a grudge about those missing volumes.”

Gurba says that as a child she didn’t realize that the Rulfo of her grandfather’s rants was one of the most famous figures in Latin American letters. “I just knew him as the friend my grandfather would not shut up about,” she says with a laugh. “I wanted to hear ghost stories, not Rulfo stories. And the irony is that I had this one degree of separation from the greatest ghost story writer in all of literature!”

From her bag, she produces a dogeared copy of “Pedro Páramo” published by Mexico’s Fondo de Cultura Económica (think the Mexican version of Penguin Classics). The mustard-colored cover features an expressionistic painting of a canine. On the inside cover, Serrano Ríos has dedicated the book to his daughter — Gurba’s mom, Beatriz: “Beautiful daughter: this is one of the most important novels in the Spanish language.”

Muñoz’s stories are peopled by furtive figures who grapple with survival and loss. His most stunning depiction, however, is of the Central Valley itself

The most disconcerting and enthralling essay in “Creep” is the final one, which delves into her three-year-long relationship with the abusive Q. To describe it in too much detail is to dilute its power, but the abbreviated version of the story is that as Gurba was writing and publishing “Mean,” and being hailed for its narrative innovations, she was also enduring terrifying brutality at home.

On the verge of another potential turning point for her reputation, the author says she now finds herself in a much better place. “There are conditions under which I’m living that are very good,” she says, “that I did not think were achievable.”

“It is difficult to know when one has exited the fog,” Gurba writes in the final pages of the book. “There are no sign-posts and one exits gradually. The noncolor is dense, then thin, and then, if one is very fortunate, not at all.”

The fog, at least for now, is gone.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.