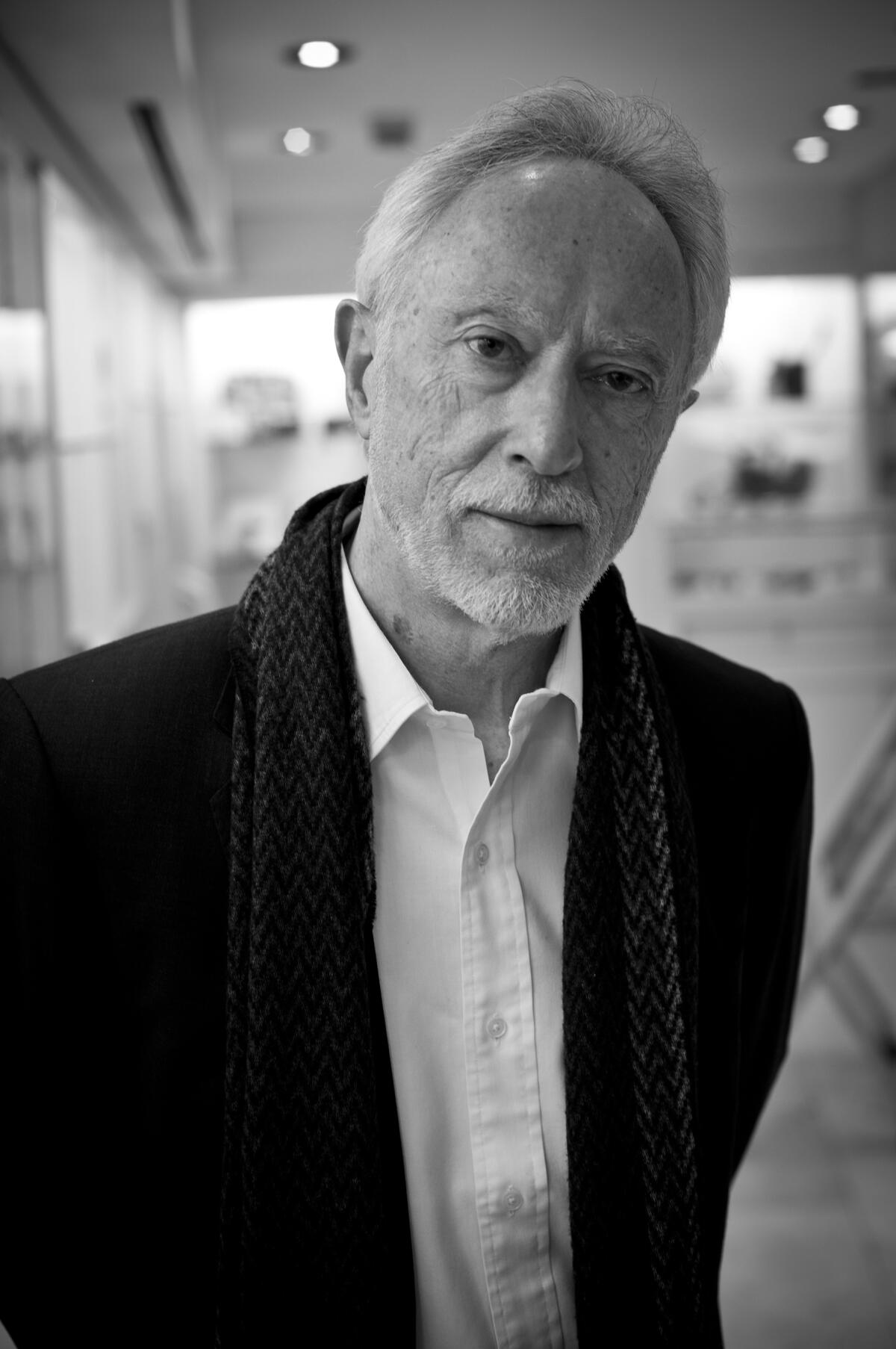

A new novel by Nobelist J.M. Coetzee, 83, is a masterclass in the ‘late style’ at its best

Review

The Pole

By J.M. Coetzee

Liveright: 176 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

I’ve long been intrigued by late style. The phrase comes from Theodor Adorno, who in 1937 defined it like this: “The maturity of the late works does not resemble the kind one finds in fruit. They are for the most part not round, but furrowed, even ravaged. Devoid of sweetness, bitter and spiny, they do not surrender themselves to mere delectation.” The idea is that as an artist grows old, an aesthetic shift occurs. Its cause is the proximity of death.

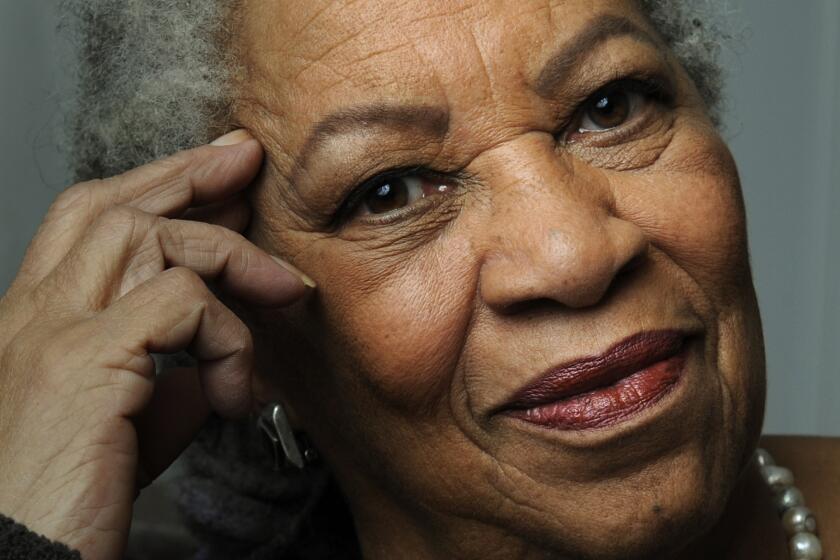

Of course, death is always proximate, more or less, but for the aging artist, it is more concrete. I think of Philip Roth’s “Everyman,” the tautness by which it re-creates the life of its protagonist. Toni Morrison’s “A Mercy,” in less than 200 pages, effectively recapitulates America’s tortuous racial history. Such efforts read like distillations; they are winnowed. Perhaps immediate is the better word.

J.M. Coetzee’s “The Pole” operates at a similar frequency: tightly focused, a late style. (The author turned 83 in February.) At the same time, it represents a return of sorts — to the spareness of his early writing as well as to his fascination with artists as characters.

Toni Morrison, the author, essayist and winner of Nobel and Pulitzer prizes, famously encouraged would-be writers to take action.

Coetzee, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2003, began his career with a breathtaking series of short novels, particularly “Waiting for the Barbarians” (1980) and “Life and Times of Michael K” (1983), which recall Kafka in subject and sensibility. Then, he took a more ekphrastic turn. His 1986 novel “Foe” reimagines both “Robinson Crusoe” and its creator, Daniel Defoe. “The Master of Petersburg” (1994) offers a fictionalized portrait of Dostoevsky. In the 1999 collection “The Lives of Animals,” Coetzee invented a literary alter ego named Elizabeth Costello. She appears as well in two subsequent novels: the eponymous “Elizabeth Costello” and “Slow Man.”

“The Pole” is not about a writer. Rather, the book, which is centered in Barcelona, Spain, charts the halting relationship between a “tall Polish pianist and [an] elegant woman with the gliding walk, the banker’s wife who occupies her days in good works.” Those good works include helping to arrange recitals at a local concert circle, where she and the pianist meet.

The woman is named Beatriz, and the story is essentially told from her point of view, although Coetzee is, as he has often been, a trickster, which he makes clear from the novel’s opening line.

“The woman is the first to give him trouble,” he begins, “followed soon afterwards by the man.” If the woman is Beatriz and the man is the Pole, then is Coetzee “him”? The effect is to create a frame or a context, to remind us that, like every story, this one is mediated, an expression of the author’s perspective as much as of his characters.

Coetzee doesn’t directly insert himself again, but it’s not the only trick in the book, stylistic or otherwise; “The Pole” is full of them. The first five of the novel’s six chapters (it may be useful to think of them as movements) comprise numbered sections, ensuring that we never lose sight of the constructedness of the work.

Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee’s allegorical ‘The Childhood of Jesus’ is not a book about the biblical Jesus but a refugee in a strange country.

The author highlights this throughout “The Pole,” mostly via Beatriz’s mind. She is charming, if deliberately self-deluding. She is content despite the fact that she and her husband have fallen out of love. Although she’s intrigued by the pianist, who is 25 years older, she keeps resisting her interest, even after she invites him to her family’s summer house. During his visit, she introduces her guest to the housekeeper, Loreto. Why would she do that if there were anything untoward?

In any case, Coetzee reminds us, “Loreto has a life of her own, invisible to her employers, which may well be full of surprises. It may contain, for instance, Loreto’s equivalent of the Pole. … It is only a matter of chance that the story being told is not about Loreto and her man but about her, Beatriz, and her Polish admirer. Another fall of the dice and the story would be about Loreto’s submerged life.”

We are thus primed for potential disruptions. Even the Pole, well into his own late style, is not too old to surprise us — or to find himself surprised. Like Dante, he is compelled by Beatriz. Or perhaps it is she who is compelled by him. “If she had to pin it down,” Coetzee writes, “she would call it pity. He fell in love with her and she took pity on him and out of pity gave him his desire. That was how it happened; that was her mistake.”

Here we have another of Beatriz’s (and Coetzee’s) counter-narratives, a lie that allows her to continue her life. If she can minimize her feelings, they will be neutralized. But emotions rarely remain so contained. “She is prepared,” Coetzee tells us, “to entertain the possibility that her story may be incomplete and even in certain respects untrue. But, looking into her heart, she can find no dark residue: no regret, no sorrow, no longings — nothing to trouble the future.” This is accurate enough, as it happens; she returns to her husband without event. Yet truth, we are left to imagine, is an illusion. Truth is another lie.

Author Philip Roth, who tackled self-perception, sexual freedom, his own Jewish identity and the conflict between modern and traditional morals through novels that he once described as “hypothetical autobiographies,” has died.

There’s more to say about this, but I don’t want to give away too much; among the pleasures of “The Pole” are the layers it reveals. It is a book not only of the living but also of the dead. What does love mean? Coetzee wants us to consider. And memory — what consolations can it offer when we know it doesn’t last?

“What has she forgotten?” he writes of Beatriz. “She has no idea. It is gone, has vanished from the face of the earth as if it had never existed.” That this is happening to all of us goes without saying. As we forget, so shall we also disappear. In “The Pole,” though, that’s no mere concept. Even Beatriz cannot keep immune.

In this deeply moving novel, Coetzee reminds us of what we wish we didn’t have to remember: that everything dissolves.

There you have it, in a nutshell: the reality of late style.

Ulin is a former books editor and book critic of the Times. His novel “Thirteen Question Method” will be published in October.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.