What a big fall novel about a creepy cabin tells us about climate fiction

Review

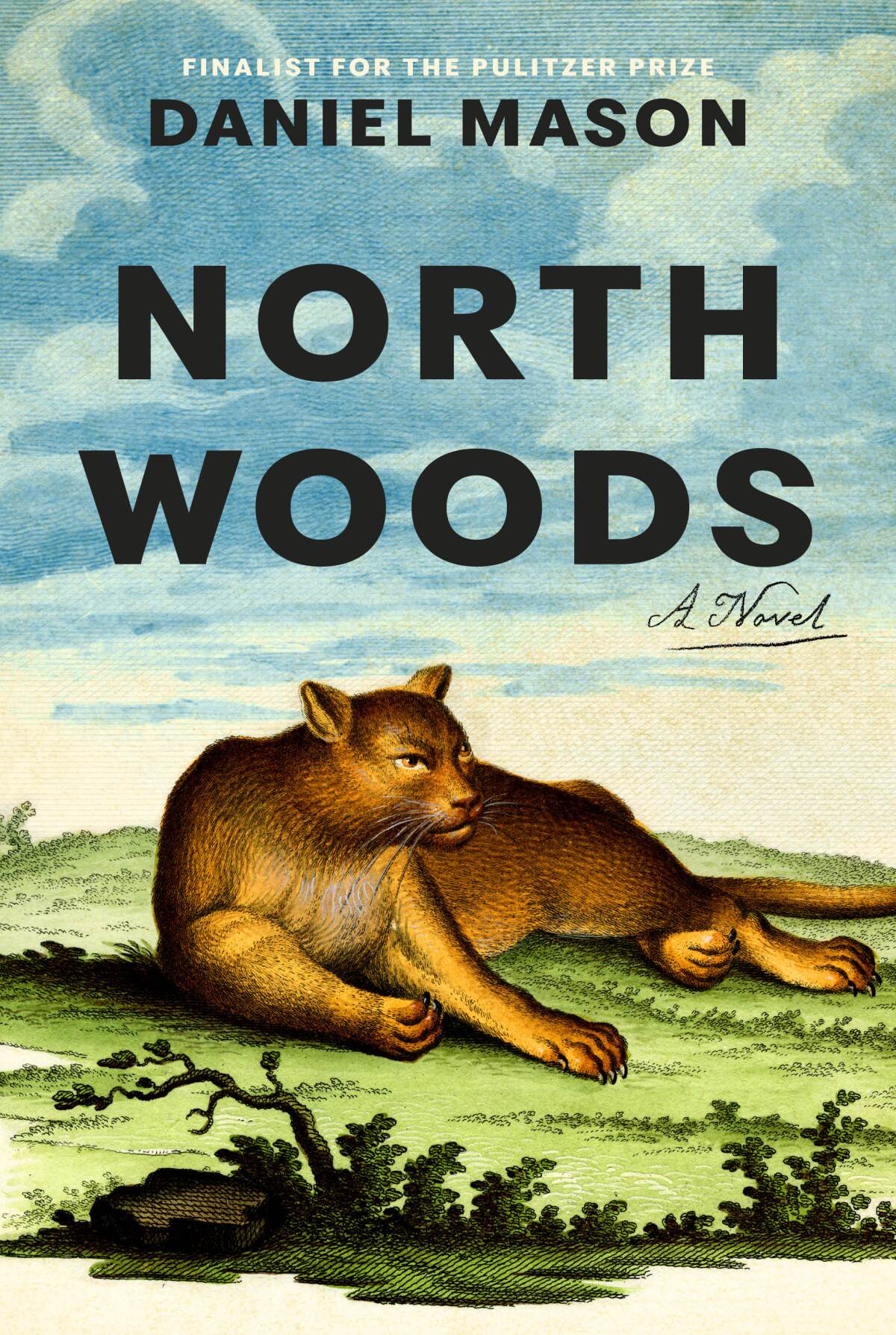

North Woods

By Daniel Mason

Random House: 384 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

We are now deep into contemporary fiction’s Lorax era: With climate change bearing down on humanity from all corners, many novelists in recent years have felt compelled to speak for the trees.

Richard Powers’ “The Overstory” (2018) towers over the genre, but there are plenty of other examples in recent literary fiction: Annie Proulx’s “Barkskins,” Elif Shafak’s “The Island of Missing Trees,” Michael Christie’s “Greenwood,” Ash Davidson’s “Damnation Spring” and more.

Ever since scientists discovered that trees have a certain sentience and capacity for communication, writers have thrilled to use them as metaphors for rootedness, loss, blight, interconnectedness — you name it.

It’s been a broken, chaotic year in life and in fiction. Authors such as Hernan Diaz and Namwali Serpell broke their novels and heroes into pieces.

“North Woods,” the fifth novel from Pulitzer Prize finalist Daniel Mason, has become one of the fall’s most acclaimed books on the strength of its innovation as a sweeping and stealthy historical saga. But it is also another tree-stuck story: Set in a patch of a Massachusetts forest, it follows the fate of multiple residents of a house across nearly three centuries. Some familiar themes of the genre apply: The tragedy of environmental devastation, the beauty of the natural landscape, nature’s stubborn capacity to endure well past human folly. But because Mason’s novel operates in such a robust variety of styles and voices, it is — perhaps more than its arboreal literary brethren — an unusually spectacular showcase of the various powerful responses that nature provokes in us, from wonderment to utter derangement.

The novel is broken into narratives featuring the patch’s occupants from pilgrim days to the present. After a simple shack is built by a couple seeking refuge from Puritan elders, a former British army major, Osgood, plants roots there, determined to establish an apple orchard. His goal, pointedly, is to create a sui generis existence fit for the New World, symbolized by his unique variety of apple: “No pampered English import, no effete Continental still reeking of the paws of some French fruitier,” he proclaims. “Mine would be wild, American!”

The all-American wildness pays off — the apple is a success. But wildness is also a problem. Osgood’s daughters inherit the fortune but spend decades embroiled in romantic jealousy and sibling rivalry. In a fit of rage, one sister takes an ax to a host of trees — and her sister as well. That harrowing event portends a series of cursed residents. An escaped slave narrowly eludes her would-be captor; two men, a poet and a landscape painter, are unable to speak their love for each other; a wealthy marriage fractures; a mentally ill man finds solace only by wandering the woods. Throughout the story, beetles tunnel through the woodwork; blight fells the trees; a catamount, referenced in rumor or song, stalks the patch. Chaos reigns. As the painter notes: “Woods, from the Old English wode . . . also meaning ‘mad.’”

John Perlin’s sweeping, civilizational history ‘A Forest Journey’ is being revived by Patagonia, the Ventura-based outfitter’s publishing imprint.

But if the episodes that make up “North Woods” are largely grim, Mason’s delivery is a pleasure, fueled by his exuberance at inhabiting the unique voices of a clutch of characters. Osgood’s Colonial-era English is elegantly braided with his crazed enthusiasm for apples, while the sisters’ story is thick with Jamesian dread. Anastasia, a would-be fortune teller, exudes a brassy, flirtatious tone with the estranged wealthy couple. Later on, an imitation of lurid true-crime magazines of the ’70s runs cheek-to-jowl with an Updikean chapter of the madman’s sister trying to close her brother’s accounts. If the world is ending, Mason is having a fine time chronicling it.

That kind of stylistic gamesmanship is as much a part of contemporary literature as the Loraxian mode: Such fragmented narratives have been at the core of recent acclaimed novels such as Jennifer Egan’s “The Candy House” or Hernan Diaz’s “Trust.” (“North Woods” also echoes Richard McGuire’s graphic-novel masterpiece, “Here,” which likewise trains its lens on one particular patch of land and its transformations across history.)

The fractured storytelling is all the better to suggest that, like the trees, humanity doesn’t operate in isolation. We’re possessed of a glorious diversity — all those voices chiming in — but ultimately, we’re all equally susceptible to fear, death and calamity.

In the same way we take the trees for granted, Mason’s story means to say, we miss these interconnections with one another or refuse to see them. To that end, the ghost-story elements that recur throughout the novel, like that mysterious and unseen catamount, are both engrossing reading and thematically fitting. We catch flickers of things that suggest a deeper, more complex, harder world but try to deny them. (History is constantly being covered up in Mason’s novel, often underneath the house’s floorboards.)

Lydia Millet, whose latest novel, “A Children’s Bible,” tackled climate change, reads new fiction on climate and argues against calling it a genre.

If we’re going to become better at being humans — and the book does become something of a climate-crisis novel in its closing pages — our salvation will come in our ability to acknowledge that history, our uglier depths. “The only way to understand the world as something other than a tale of loss is to see it as a tale of change,” Mason writes. The trees will survive. And, Mason suggests, if we care enough to keep telling their story, maybe we will too.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.