Is your family like a broken artifact? This Cuban Jewish art restorer has a book for you

On the Shelf

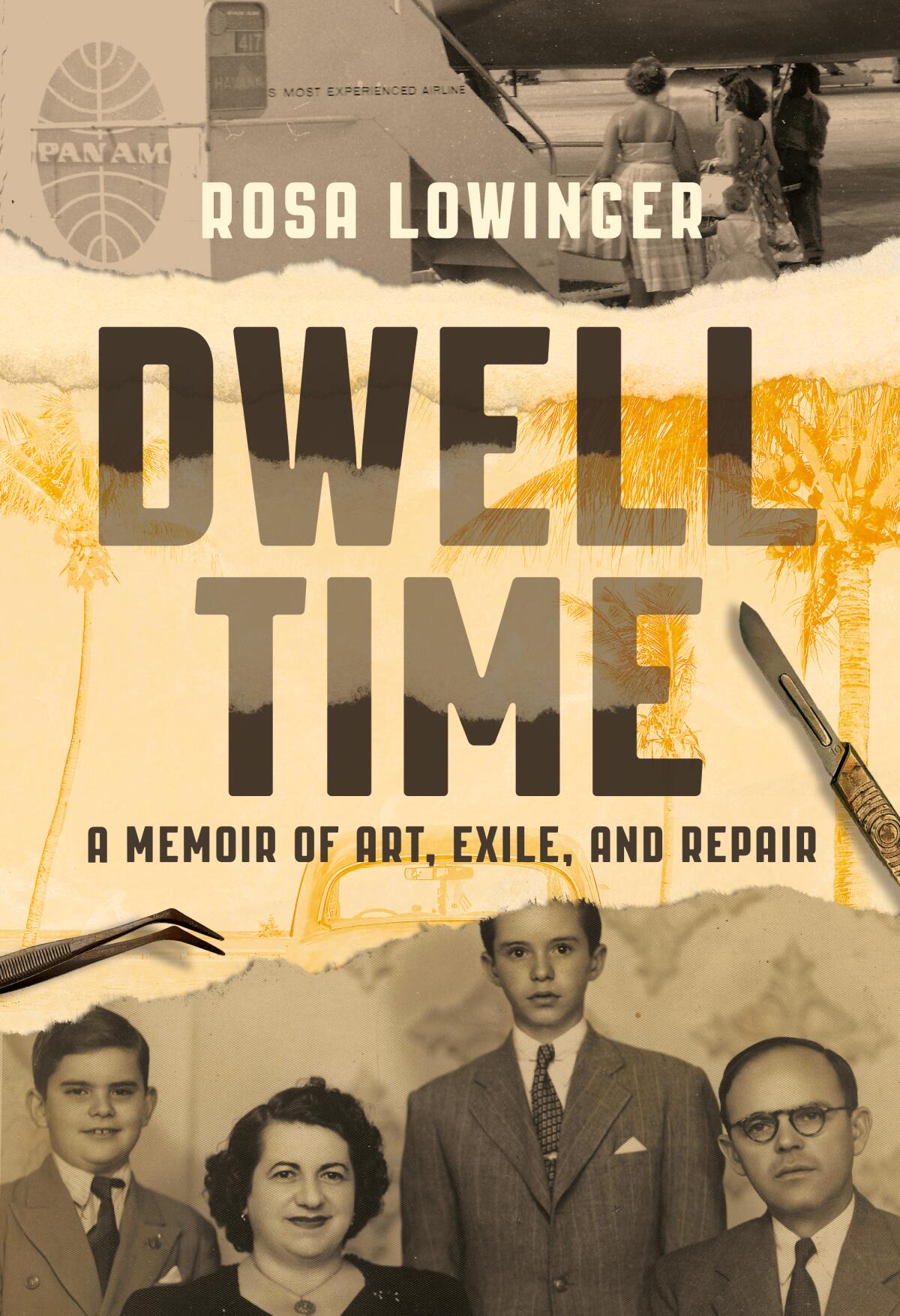

Dwell Time: A Memoir of Art, Exile, and Repair

By Rosa Lowinger

Row House: 360 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Rosa Lowinger’s grandparents landed in Cuba fleeing the Holocaust, hoping for America but not quite making it there. By the time Fidel Castro had seized power, her parents saw the lay of the land and made that final step, settling in Miami. Lowinger had wanted to become an artist, but a class in college introduced her to the art of conservation, and the rest was history — albeit a fragmented history of war, identity crisis and intergenerational trauma.

The author of two books on Cuba, Lowinger is the founder of RLA Conservation, one of the largest woman-owned firms for art and architectural conservation in the country. And restoration is the persistent metaphor of “Dwell Time,” Lowinger’s recent memoir.

Her parents, who never quite grasped her work as a conservationist, also struggled to navigate their own losses. “My whole life has been a disaster,” Lowinger’s father said to her as that life’s end approached. “Dwell Time,” the result of his daughter’s professional and emotional restorative work, shows how the pieces can be put back together — even if the whole will never be quite the same.

Lauren Elkin explains the inspirations and surprising opinions behind her new book on women artists, ‘Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art.’

Lowinger will visit L.A.’s Skirball Center on Sunday to discuss “Dwell Time” with Cuban visual artist Alexandre Arrechea. She spoke with The Times late last month about her life’s work, in a conversation edited for length and clarity.

Your first two books are also nonfiction, but “Dwell Time” is much more personal. What sparked the idea to write a memoir?

I was awarded the Rome Prize in 2008, and I was wandering through their library. I stumbled upon “The Periodic Table” by [chemist and Holocaust survivor] Primo Levi, about his family who were Piedmontese Jews. He had written many memoirs as a survivor of Auschwitz, but this is about chemistry and his family. And I thought: There is a book about conservation here. Very few people understand what it is that we do. I knew I needed a family story to wrap it around, and I knew it would be personal, but at the time, the two pieces felt very separate.

When the pandemic happened, I took a writing class online and I started working on a novel about Havana in the 1950s. I hired a book coach, and during our first meeting I mentioned the other idea about the family memoir, and she said, “Listen, write a book proposal for that. That will sell.” But she was wrong! It didn’t sell. Many agents didn’t want it. And then years later Row House Publishing approached me and said, “We want to publish it, but we need it in 10 months.”

Did you ever finish the novel?

I’m working on it now!

How did it feel to share some of the more personal elements of your story, like the breakdown of your first marriage? What was the most difficult section to write?

I thought the personal stuff would be the sprinkles on the cupcake about my work of art restoration and conservation. And my editor said no, it’s the other way around, the family story is the cake and the work is the sprinkles. At first I resisted. I didn’t want to unpack my own foibles. I didn’t write about my son. I didn’t use my ex-husband’s name.

But, as you crack open the story, I had to crack open mine. As I was writing about my mother, who is charismatic and funny but monstrously destructive, I would have to get up and hyperventilate and bit. It wasn’t painful, but it felt like surfing in the Pacific Ocean. It was like tightrope walking.

Cuban artist Alexandre Arrechea, who has a solo show at MOLAA, discusses his interest in design and the set he created for the Birmingham Royal Ballet

When I finished, I knew I had to show it to them. I had to show it to my ex-husband, my son. Both approved the book. If my father had been alive, there’s no way I could have written this. But my mother has a great deal of strength. I showed her things out of order, in bits and pieces. When she encountered the finished book, she suffered with it. But she got over it. She came to my reading, and she’s organizing a reading at her assisted living center.

The blessing for me in all of this is that I can always see the best in her at this point in my life. We should all have to interview our parents at length, because then you can look at them through different eyes.

Have current events changed your thinking about the book, given your family’s story as immigrants in the Jewish diaspora?

This book was published on October 10. On October 7, I’m thinking about my book, and I’m faced with the world suddenly cratering. I was very unsure. I’m not at the center of this dialogue, but I wrote about finding a path to repair through recognizing damage, and that’s a metaphor for everything that is going on now — people don’t recognize their own humanity.

I thought a lot about this — you can have a work of art that’s perfectly gorgeous but if it has one scratch in it, that’s all you’re going to see. It’s true with people, also. Human beings are repairers; we hope to fix things. But we hope that we can reach the work before it’s past all hope. It’s much easier to eat well and exercise than to have open heart surgery. The thing about anger and violence and flares of hatred that they come with more potency than measured, calm, quiet thinking.

You describe how the most important thing a conservationist can do is understand the damage.

When something breaks, we have a strong reaction to its brokenness. We have something that lived in history. This also applies to people! Whose parents don’t have damage? Whose parent doesn’t inflict damage? It’s baked into ourselves.

A federal court Tuesday rejected a Jewish family’s decades-long legal fight for a famous Pissarro painting that was taken from them by the Nazis at the dawn of World War II and is currently at a museum in Spain.

What is your take on the art world’s inherent vice, the theft of works from non-European countries? Do you believe these artworks should be repatriated?

I’m not a decision-maker, but once someone decides to return the Elgin Marbles to Greece, my people will have to figure out how to clean them, transport them. We’re technical helpers. But my opinion is that history is a continuum and what is appropriate evolves. We’re in a moment where we are having international awareness of care.

The first step is looking at the problem and being able to visualize the possibility of the success of the project. Repair on a human level is the same way.

Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.