Hollywood’s Fort Knox is Iron Mountain. Its latest restored treasure: Bee Gees footage

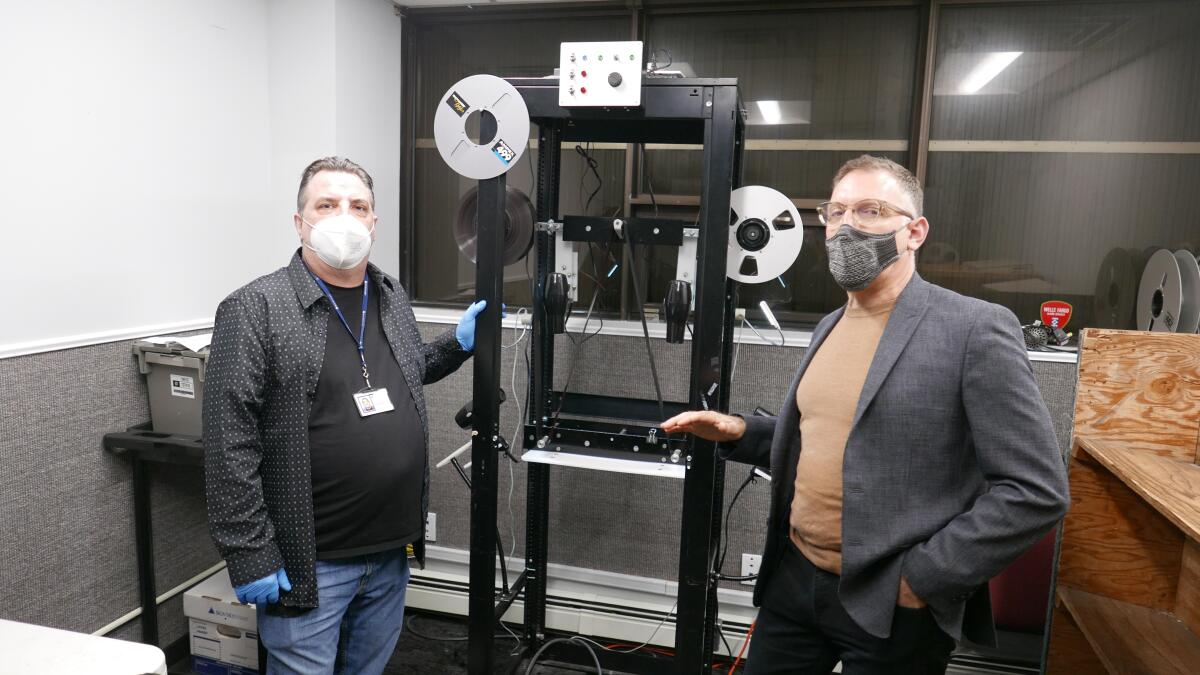

It’s been several decades since a TV show was recorded on a two-inch Quadruplex videotape machine. Kurt Spada, lead encode operator for Iron Mountain Entertainment Services, remembers working on one early in his career as a TV technician.

Fortunately, he still knows his way around the piece of equipment, which was first used during the advent of videotape in 1956 and now looks like a set piece from a vintage “Star Trek” episode. On a November afternoon in the Moonachie, N.J., facility, he was transferring tapes of programming from the 1960s into a software system that converted them into digital files.

For the record:

3:46 p.m. Dec. 9, 2020An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect title for the HBO documentary “The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart.”

“As long as you’ve got the proper equipment, you could probably play this 100 years from now,” Spada said. “But most of that equipment is hard to find, which is why people are taking their material and digitizing it for whoever wants to view it.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic has turned the past into the present for the entertainment industry, expect to see some of that content on a streaming service soon.

The creation of new shows and movies has been slowed by the health crisis while the appetite of homebound consumers looking for content is intensifying. The demand is sending media companies into their vaults to supply streaming services and documentary filmmakers, lending sizzle to the unglamorous business of archiving and restoring film, video and music assets.

The steady work flow has boosted the entertainment services unit of the Boston-based Iron Mountain, which was founded in 1951 with a mandate to protect documents, films and other media from destruction in the event of a nuclear attack, back when Cold War fears consumed the national psyche. Its main storage facility is an underground limestone mine built in Boyers, Pa., that goes 22 stories underground.

Iron Mountain, which had $4.26 billion in revenue last year, does not disclose finances for its entertainment services unit, known as IMES. But the company said it had double-digit revenue growth this year because of increased usage of archived material.

“Our business has been stronger in this period,” said Lance Podell, senior vice president and general manager for IMES. “If no one’s producing, we still have to find content to entertain you.”

Three major streaming services have been launched in the last year, with two — WarnerMedia’s HBO Max and NBCUniversal’s Peacock — arriving after the pandemic brought much of the production business to a standstill. Media companies have mined their storage files for vintage assets to give consumers a robust selection of shows and feature films. Iron Mountain’s clients include major film and TV studios; HBO; several sports teams, including the Los Angeles Lakers; the Grammy Museum and the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

Record labels also have been scouring their files to make vintage video and audio available for streaming on YouTube, a project Iron Mountain has underway for Universal Music Group.

“With COVID, I think there’s been a huge premium to being able to have editors in a room by themselves with archival material or being able to safely shoot really small-footprint contemporary interviews with two people,” said Nicholas Ferrall, president of White Horse Pictures, which has worked with IMES. “The doc world has been able to continue going inside this really tough environment.”

Iron Mountain has about 650,000 square feet dedicated to IMES, with locations in Boyers, Hollywood, London, Paris and New Jersey. Each site is equipped with temperature and humidity-controlled storage facilities and studios where technicians can remediate, restore and digitize old analog media.

The move to add those in-house services in recent years has proved invaluable during the pandemic when access, travel and production throughout the TV and film industries have been limited because of social distancing.

“When no one’s trucks were on the road and no one was transporting any material, the projects we had continued — nothing stopped,” Podell said. “The more material they wanted to digitize the more we were able to deliver because it was sitting in our warehouses. No one has to travel anywhere and risk their health and safety. We can access it all and upload it to them. It never has to leave the building.”

One of the New Jersey facilities is located in a utilitarian two-story red brick building in Moonachie, a modest suburb near MetLife Stadium. Inside are the original tapes from many of the biggest entities in film, TV and music — most of which cannot be named publicly due to client confidentiality. But the scope and cultural value of the stored holdings are clear when a visitor scans the thousands of labeled boxes in the location’s vaults.

Iron Mountain Entertainment Services became more than an archive after its 2007 acquisition of Xepa Digital, which specialized in restoring and preserving outmoded audio and digital tapes.

Rae DiLeo, a recording engineer and studio manager who joined Iron Mountain in 2008, said Xepa was started by some of his peers in Los Angeles who were appalled over how their tapes were being handled in transit.

“The story goes that they were having assets delivered for a mix to their home studios and they would come back from the lunch and find them sitting on the porch and baking in the sun,” DiLeo recalled. “They said ‘There’s got to be a better way to do this.’”

The work of IMES and other archival services will be on full display for viewers this Saturday when HBO and HBO Max premiere White Horse Pictures’ “The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart,” a new documentary by director Frank Marshall. It chronicles the Australian pop group’s enduring career spanning five decades, including its phenomenal reign on the music charts during the disco era that was rivaled only by the Beatles’ dominance in the mid-1960s.

Inside a 260,000-square-foot warehouse just over the Grapevine off Interstate 5, an archivist from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences clambered up a ladder to inspect a stack of dusty 35-millimeter film cans.

Video and audio material from Universal Music Group, which owns the RSO record label where the Bee Gees had their biggest hits, were accessed for the two-hour film. Among the 23 film reels restored for use were eight-millimeter home movies of the Brothers Gibb as children growing up in Australia.

The story is also told through vintage tape of TV interviews and performances. The group’s longevity means its career was captured on an alphabet soup of obsolete video (3/4 inch U-matic, Beta SP, Digi Beta, VHS and HD Cam) and audio formats, from two-inch multitrack reels to small cassettes — one containing a demo recording of the song “How Deep Is Your Love” from the massively popular “Saturday Night Fever” movie soundtrack.

“A lot of the stuff had been sitting in these pallets for decades and no one had really touched it,” said Aly Parker, a producer on the film. “I’ve worked with other [archive] houses, and they’re all great. But Iron Mountain probably has the most capabilities. If you’ve got something weird, you take it to them.”

Before the tapes could be played on analog tape machines and transferred to digital files, many had to be baked — where they are placed in an oven at low heat to extract moisture that accumulates over time. Moisture on the tape could result in it sticking to a head during playback.

In order to play tapes recorded in obsolete formats, Iron Mountain’s Moonachie facility contains an array of vintage video and audio playback machines wide enough to supply a museum of 20th century recording technology.

Upstairs from the large two-inch Quadruplex video machine is a menagerie of devices dating to the 1940s, such as hand-cranked moviolas. The collection of audio tape machines — some the size of a kitchen oven — include models from Studer, a Swiss manufacturer considered the Rolls-Royce of recording studio equipment through the 1980s. Replacement parts can cost hundreds of dollars on EBay.

All of the machines need to be operational as an archived original tape might only play in the format it was recorded on. Keeping the aging equipment running can be a source of anxiety for Kelly Pribble, principal studio engineer and preservation specialist for IMES.

“There is a guy who builds them here in New Jersey,” Pribble said. “He’s 74 years old, and I am afraid if something happens to him I’m going to be in big trouble. It’s a challenge for me to find guys who are still alive who can work on these things.”

What worries Pribble more is the deterioration of source tapes. A veteran audio engineer who learned his craft at the legendary Quad Studios in Nashville, he has become an evangelist for the care and restoration of media, giving seminars to entertainment industry groups around the world and at the Library of Congress. He has also had private meetings with record label heads to level with them about how the historic content they own is at risk.

When Pribble gives slide presentations showing deteriorating tape reels that may have been sitting for years in a damp basement of their owner, he can sound like a physician discussing a seriously ill patient.

“I’ve said, ‘I don’t want to scare you, but I want to show you what’s happening to your masters,’” Pribble said.

Pribble has gone to mechanical engineering school at night and learned how to build his own devices and safely clean video and audio tape. One Rube Goldberg-like setup he created uses handheld hair dryers on the tape as it runs through a spool after being soaked in distilled water.

“I’ve probably cleaned 4,000 to 5,000 tapes that are moldy just like this,” he said as he displayed a white cardboard box with an encrusted tape reel inside. “The mold is actually eating into a tape and is going to degrade and deteriorate over time.”

Pribble applied his restoration skills to tapes in the Bob Dylan archive, which is being prepared for the 2021 opening of the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla. Thousands of items from the singer’s career will be curated and exhibited at the site.

The maintenance of a master tape — the most accurate representation of an original recording — is necessary even after its content has been transferred to a digital source. Archivists will want to transfer information from the original tape again whenever new technologies with higher resolution come along. (During a reporter’s visit, Pribble was at work upgrading an instantly recognizable Motown track, which when played sounded like the artist was in the room.)

“Formats constantly change and digitization is consistently getting better,” Podell said. “The fact that something is digitized 10 years ago is kind of irrelevant now. It needs to be redigitized. So there is an annuity in a way as a business because technology continues to evolve.”

Some media companies have learned the hard way about the value of preservation. Universal Music Group was in the process of moving its assets to Iron Mountain in 2008 when a fire broke out on the Universal Studios lot where some recordings were stored.

While UMG has maintained the number of recordings lost in the fire is much smaller than what was reported, the company now says, “The majority of our assets are stored in a facility recognized as one of the most secure on Earth,” according to an internal memo sent to staff in March by Patrick Kraus, senior vice president for archive management at UMG, that was viewed by The Times.

The UMG fire suppression methods have become top-of-mind throughout the industry. At the Moonachie facility, IMES holds an annual disaster drill, where employees are presented with a mock scenario such as a plane crash or hurricane and then develop a response in real time on how to protect the assets inside.

“This is cultural heritage,” said Brian Towle, director and global head of operations for IMES. “There is a point that when you can’t hear it and you can’t play it, it’s gone.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.