How L.A.’s black-owned music companies hope to change an unjust record business

In 1977, Richard Griffey opened the doors on Sound of Los Angeles Records. Formed from the ashes of Griffey and Don Cornelius’ Soul Train Records imprint, SOLAR became one of the definitive independent voices of Black music in the late ’70s. Acts like Shalamar (featuring future solo star Jody Watley), the Whispers, Midnight Star, Dynasty and Klymaxx all enjoyed a string of hits, but perhaps even more importantly, the label was a nexus for a new generation of producers and executives like Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds and Antonio “L.A.” Reid who would go onto reshape American pop through their music and entrepreneurship.

“[Griffey] was a genius in many ways in terms of what he built, creating the label at the time that he did it. He created music with a force behind it.” Edmonds told The Times in 2010, after Griffey’s death. “He was a Black man to the depths, he was a Black activist. He believed in Black businesses and Black people standing on their own two feet.”

In the midst of roiling protests against police brutality, and a pandemic that’s disproportionately killing Black people, there’s again a profound hunger for independent, uncompromising Black art and business. Leimert Park’s Eso Won bookstore has been overwhelmed with orders of antiracist literature, and lists of Black-owned restaurants in L.A. are funneling dollars to struggling owners. SOLAR was a model many others are living up to right now.

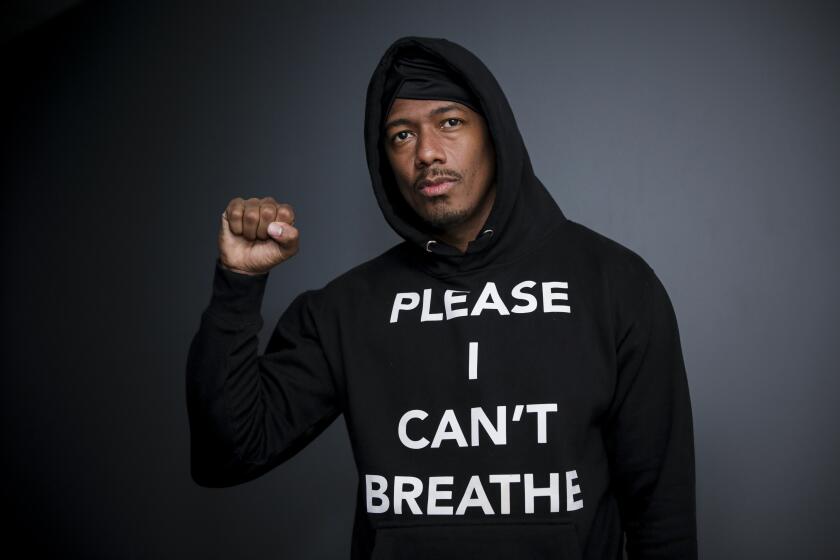

Across L.A., hip-hop morning-show hosts such as Power 106’s Nick Cannon and Real 92.3’s Big Boy have led daily discussions on the protests against police brutality

While music made by Black artists already dominates streaming, making major labels and streaming companies rich, many are again questioning how those conglomerates are supporting essential causes like Black Lives Matter, or properly paying the people who make and support the music. “No one profits off of Black music more than the labels and streaming services,” said The Weeknd (Abel Tesfaye), announcing a $500k donation to three bail and legal initiatives. (The three major record companies — Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group and Sony Music Group — and top music streamer Spotify have all announced multi-million dollar funds to support anti-racist groups.)

If you’d like to pay Black artists and company founders yourself, The Times has compiled a list of entrepreneurial music ventures owned by Black Angelenos. Venues like the World Stage in Leimert Park will likely be closed for a while because of COVID-19, and there are too many excellent independent Black artists for one list here. So we focused on music labels and artist-founded companies where you can spend or give money today.

A maverick guitar designer

As the ferocious lead guitarist for the prog-metal band Animals as Leaders, Tosin Abasi often pushed the limits of his instruments. To play how he wanted, he needed to build a line of extended-range guitars himself.

“I found it really gratifying to design an object that spoke to me,” Abasi, 37, said, of founding his 3-year-old SoCal-based guitar company Abasi Concepts, whose seven- and eight-string guitars have an abstracted, almost hieroglyphic quality to their body shapes. Technique-intensive players from jazz to country have championed his instruments, “but it has been kind of crazy,” he said. “Guitar builders are strong personalities, and they can be really different from those you meet in the [artistic] space.”

At metal festivals and theater gigs, Abasi was often one of few Black people in any professional sphere he walked into, even moreso as a guitar designer navigating the instrument-manufacturing industry. Abasi acknowledges he’s had few public-facing luthier peers of color. But the current reckoning around race and opportunity has started to upended his corners of the music world as well.

“I’m conspicuously Black in a lot of these spaces, but there’s a weird silence around it. It’s never the point of conversation, but race can be present in ways like silence too,” Abasi said.

“My fanbase obviously resonates with support for the Black experience, but I’ve seen fallout from peers who spoke about it and lost hundreds of followers. There’s never really been a conversation about it in metal. Now that it’s so public, when a moment like this comes up and you think have shared values, it’s interesting to see who rejects them.”

Abasi’s been having the whole being-Black-in-metal conversation for his professional life and is still perplexed by the currency that virtuoso talent lends him even to fans who hold retrograde ideas about race. Black progenitors of rock — Chuck Berry, Sister Rosetta Tharpe — proved what the electric guitar was capable of right out of the gate. Even if metal likes to think of itself as a meritocracy, there’s plenty of change there that’s long overdue.

“For me, music is transcendent over division,” Abasi said.”But there’s an irony there because the racist past in the U.S. is complicated. They’ve accepted Black culture but didn’t accept Black people. But expectations can be disrupted by music, that’s its function. ”

Acclaimed singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers on her new album, “Punisher,” defunding the police, therapy and the virtues of Ryan Adams clickbait

A club-music collective with a resonant message

Over the sound of a cocking gun and a deep kick drum, the Black activist Tamika Mallory sounds especially gripping: “The reason why buildings are burning is because this city, this state would prefer preserving that white nationalism and that white supremacist mindset over arresting and charging and helping to convict four officers who killed a black man. That is the reality of what we’re dealing with.”

So begins “State of Emergency,” a new single sampling Mallory’s May 29 speech about the former Minneapolis police officers now charged in the death of George Floyd, released last week on the indie L.A. club-music imprint Juke Bounce Werk. Charged, urgent and insistent on change, the track is the latest in a long catalog that speaks to how queer people of color have often invented and driven underground club music and how that nebulous modern music scene is rising to meet the present moment of upheaval.

“Some days it’s exhausting, some days it’s inspiring,” said Alexis Gutierrez, 47, cofounder of the now dozen-strong, multiracial collective. “There’s a lot of things bubbling to the surface, and we’re seeing the adversities that had inhibited our growth along the way. When you’re in it, you don’t want to see it. Now you’re forced to see it. You’re seeing people of color rebuild and take control back of their industry.”

The label’s been active since 2014, and while the range of sounds can’t be pegged to any one dancefloor — footwork, old house, screwed-up R&B and lonely after-hours instrumentals — it’s a coherent vision of nightlife as a catalyst for change. They may even have a breakout star in Kush Jones, the Bronx producer whose dazed and propulsive juke-inspired tracks have struck a chord with a quarantined audience desperate for dancing.

The last few weeks have been heavy, Guttierez said, but also a chance to demand more and do things differently. The shift in understanding that this moment of protest has brought will resonate across activism and culture.

“We’re all waking up. People around us feel a shift and this may be one of the only opportunities to redirect things,” Gutierrez said. “Everything’s been turned over on its head because the old way wasn’t working. We could fail, but let’s have as much integrity as possible.”

Vegan takeout from an enterprising South L.A. rapper

After traditional sources of income for musicians dried up because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the independent rapper Hugh Augustine reinvented himself and opened Hugh’s Hot Bowls, a takeout food service that sells vegan meals.

“It’s given me some sense of normalcy and something to look forward to in my day,” he said. His community in South L.A. is considered a food desert. “There are no vegan cafes or restaurants or anything. There’s only a select few healthy food options around here. So I said, ‘Why not try to start something even if it’s small, where I can provide the service that I’m looking for?’”

Heather Hutt, Augustine’s mother, was his first boss. He worked for her catering company in high school, and several of her lessons, such as making each meal look pretty, went into the model for Hugh’s Hot Bowls. “He soaked everything up like a sponge, osmosis,” Hutt said.

Augustine has sold more than 700 Hot Bowls in 12 weeks. At $10 per bowl, they’ve more than made up for the money he would have gotten from a coronavirus-canceled tour. Running the restaurant reminds him of watching the late rapper and entrepreneur Nipsey Hussle sell CDs in the school parking lot.

“He was fearless in his endeavors,” Augustine said. “That’s always been something that kinda has held me back in the past, being afraid of judgment.”

An illicit dance party, held in a South L.A. warehouse on Friday night, may have been the city’s first live music event since the coronavirus shutdown.

A label, a T-shirt company and dipped grapes too

After watching his grandmother work tirelessly for little reward, the MC G Perico knew he wanted to be his own boss. He made his name as one of the city’s elite gangster rappers through his So Way Out imprint, then got a deal with Roc Nation, where he released last year’s “Ten-Eight.” Now, he’s building up another independent label, Perico’s Innerprize.

Beyond the music, G Perico, 30, has an entrepreneurial presence throughout the city. When the South L.A. native felt “pigeonholed” by his previous branding, he started his latest clothing company, Blue Tshirt, which comes from his desire to dismantle stereotypes about gang culture.

“Blue Tshirt is basically creating your own world, how you see it and how you perceive the world and whatever you wanna do,” he said. “It’s basically like no limits on anything.”

He’s also involved in the food industry as a co-owner of DD’z Treatz — a luxury dessert company that sells dipped grapes — and has a juice bar in the works.

In light of national protests against racial injustices, G Perico sees value in the recent push toward Black-owned businesses, especially given how the United States has prioritized capitalism.

“If everybody is financially literate and knows how to handle business and recycle money amongst each other, it’ll be a whole lot less police brutality, a whole lot less criminalization,” he said. “With a strong economy brings power.”

Fostering self-reliance in Leimert Park

The MC Ill Camille purposely maintained independence to have control over her music, even if it’s not always the most financially secure route.

“You can’t put a price on peace of mind,” she said of her self-financed label, Illustrated Sounds. “That’s what independence gives me. On and off these records, I have to own myself and my message. It’s important to me as a Black woman and a creative to represent in true form without that being watered down.”

Her 2017 album, “Heirloom,” showcased a warm blend of storytelling and soulful introspection. Besides releasing music as a solo artist, Ill Camille is half of Harriett, a duo with fellow independent artist Damani Nkosi. Their self-titled project was released on DAMCAM, another imprint that stays true to her stance on self-ownership.

Camille hosted the “Harriett” release party at Black-owned Hot & Cool Cafe in Leimert Park and helped organize the community’s Juneteenth celebration. She always carries physical copies of her latest music, so anyone she happens to meet can walk away with a lasting impression.

On his first album of original material in eight years, Bob Dylan sings of betrayal, dismemberment and rock ‘n’ roll.

22 more black-owned companies in L.A. to support:

4Hunnid: YG wrote the best anti-Trump song of the 2016 election and kept it up in 2020 with the scathing protest single “FTP.” His fashion line updates Compton silhouettes for the modern streetwear scene.

Aftermath Entertainment: You can’t tell the story of Black music in L.A. without Dr. Dre’s world-crushing imprint, which boosted the careers of Eminem, 50 Cent, Anderson .Paak and a sea change in hip-hop’s commercial potential.

The Artform Studio: One-of-a-kind record store and salon from Sherry and Adrian Younge, where her hair and makeup virtuosity makes a natural complement to his wide-ranging tastes in records.

Brainfeeder: Flying Lotus’ longtime label has put out monumental works of contemporary jazz from Kamasi Washington, deranged funk-fusion from Thundercat and reams of experimental electronica from L.A. and beyond.

Diamond Lane Music Group: In-house label for Compton’s staple MC Problem, who recently wrote, directed and starred in his short-film debut on Tidal.

Glydezone: DaM-FunK’s Culver City indie label releases the more out-there ends of his spacey, suave and grimy funk jams.

Golf Wang: Tyler, the Creator won his first Grammy this year, but his fashion line has shaped a whole skater-dad aesthetic in hip-hop for nearly a decade and its Fairfax store is always packed.

L.A. Club Resource: The sometimes challenging, always cool-beyond-cool label from producer Delroy Edwards, whose sounds range from reissued Southern rap to Berlin techno and weirdo synth-pop.

Linear Labs: Adrian Younge’s label venture sports records from Ghostface Killah and Ali Shaheed Muhammad (A Tribe Called Quest).

Lo Phat Cabs: Paul Tidwell’s shop builds amps and speakers for bassists and instrumentalists looking for the sub frequencies essential for modern pop, R&B and hip-hop.

The Marathon Clothing: The fashion store from the late Nipsey Hussle is a reminder of his resonant legacy in South L.A. activism. Although the brick-and-mortar store — the site of Hussle’s murder — has closed, it’s still a pilgrimage site and is online selling custom facemasks.

Other People’s Money: Rapper Dom Kennedy’s label and streetwear line has been going strong for a decade in L.A.

KJLH 102.3 FM: Stevie Wonder, delightfully, is behind the only Black-owned FM radio station in L.A., a mix of news, commentary and uplifting music programming.

Rappcats: The brilliant producer Madlib has a home base in this Highland Park off-and-on pop up for vinyl (by day it’s his office for Now-Again Records), and you can browse much of the source material he and co-owner Egon use to craft hip-hop instrumentals.

Rave Reparations: Alima Lee, a multifaceted DJ, artist, filmmaker and promoter, co-founded Akashik Records, a home for cutting-edge electronic and beat music. But her current project Rave Reparations is an underground nexus (part promoter, part radio show, all progressive worldview about club music) linking Black DJs with bookers and charging sliding payments for marginalized fans.

Shop The Homies: L.A.-rapper and entrepreneur Dreebo has a popular fashion line touting SoCal pride and camaraderie. You can customize most items to broadcast your particular hometown.

Soulection: Longtime L.A.-based label collective of left-field beat music, futuristic soul and much more. They have a show on Apple Music that’s a lovely evening wind-down.

Sounds of Crenshaw: Saxophonist Terrace Martin strides between L.A.’s jazz and hip-hop worlds, equally at home with Kendrick Lamar and Herbie Hancock. Sounds of Crenshaw is his personal home label.

Top Dawg Entertainment: The label that broke Kendrick Lamar, SZA and ScHoolboy Q needs no introduction in L.A., and even as an Interscope imprint it still has an activist footprint across South L.A.

WinslowDynasty: While building a well-regarded career working with Justin Timberlake, Dr. Dre, Beyoncé and many more, trumpeter/producer Dontae Winslow also runs his own record label.

World Famous VIP Records: Long Beach’s landmark for hip-hop was the birthplace of G-Funk and helped shape stars like Snoop Dogg and Warren G.

Yours Truly: Fairfax streetwear shop from the Anaheim rapper Phora, which has become a coveted label in its own right among local skater denizens.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.