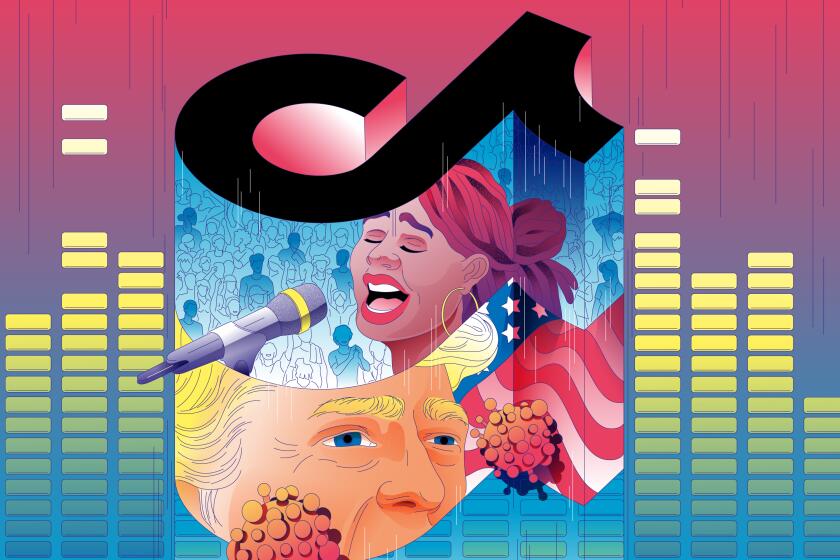

Black creatives helped turn Clubhouse into the next tech unicorn. But who stands to gain?

- Share via

When the invite-only, live-audio-chat app Clubhouse debuted in the spring of 2020, it was mostly an insular community for venture capitalists to talk about initial public offerings and return on investment. But over the last few months, as rappers, producers and music business executives flocked to it, Clubhouse became the central node for the hip-hop industry to talk shop, make connections and start flame wars.

Stars like Meek Mill and 21 Savage will show up as guests among the regulars. Taste-making executives like Columbia Records’ Phylicia Fant, Top Dawg Entertainment’s Terrence “Punch” Henderson and Motown’s Ethiopia Habtemariam are members. Rising producers have had their lives changed by chance encounters with stars.

While countless niche interests are up for discussion on Clubhouse, the rap industry was a major factor in pushing the app to an estimated $1-billion evaluation in just nine months.

But the app, which counts around 2 million users, risks hate speech and conspiracy theories as it grows, like all social media do today. Clubhouse made an early push to attract Black users, but expansion risks the alchemy of privacy and connection that makes it interesting. Some rap-world figures are skeptical about helping drive a new billion-dollar app for other investors’ portfolios.

“The Clippers are driven by Paul George and Kawhi Leonard, LeBron [James] and Anthony Davis drive the Lakers. It’s the same thing with these apps. Clubhouse was driven by Black and Latino culture,” said Percy Miller, the hip-hop impresario behind No Limit Records known as Master P, and who recently partnered with a former Tesla engineer on a next-gen Black-owned car company, Trion. “Black culture drove it to a billion-dollar valuation, so we’ve got to start thinking about being producers instead of just consumers.”

Meek Mill’s “Championships” is nominated for best rap album, the culmination of a year in which he was finally freed from a harrowing ordeal with the judicial system.

Clubhouse’s ability to cater to the rap world, for now some of its most fervent users, will show a lot about its future — and whom it values.

“Communities of color drive the cultural conversation and a lot of the initial wealth creation for apps like Clubhouse,” said Mercedes Bent, a partner at Lightspeed Venture Partners, a venture capital firm where she scouts startups with founders and audiences of color (the firm was in early talks with Clubhouse but did not invest). “On Snapchat and Vine, Black people were over-represented in the usage, which made it cool and aspirational. There was definitely a concrete effort from the founders to get Black people on the platform. But how do you reward those who drive it?”

Clubhouse’s architecture combines elements of a Zoom conference call and old-fashioned drive-time radio. Hosts create pop-up rooms, either scheduled or spontaneous one-offs, where users gather to talk (the host moderates and determines who can talk or enter the room at any time). Almost every subject including psychedelics, parenthood and fake-orgasm contests are covered somewhere. Late Sunday night, users flocked to hear Tesla founder Elon Musk interview Vladimir Tenev of the embattled finance app Robinhood.

It’s very much a product of its pandemic-era moment: private and real-time enough to share freewheeling ideas, but with enough well-connected users to make it serendipitous. For hip-hop fans and artists, it’s proved more captivating than well-scrubbed Instagram, and more conducive to real conversation than TikTok.

“About two weeks after I got on the app, I was in a room where someone asked a male artist about current state of rap, and he mentioned ‘women doing pussy rap stuff,’ and a lightbulb sort of went on,” said Mikeisha Vaughn, a Columbus, Ohio-based culture writer who founded a popular room on Clubhouse, “Pussy Rap and All of That,” with a crew of Black women journalists (Robyn Mowatt, Laja H and Kia Turner) she met on social media. “Women rapping about their sexual prowess get a lot of flack. I stand firm about women talking about whatever they want, so oh yes, I was gonna start a room about it.”

Every Wednesday, Vaughn’s co-hosts dive into the issues and achievements of women in contemporary rap. Her subjects noticed — Grammy-nominated MC Rapsody popped into the forum a few weeks ago. Erica Banks, of the wildly popular “Buss It” single and viral TikTok dance, swung by too.

In December, the rising L.A. rapper Symba hosted a room to dish about his new release for Atlantic Records, “Don’t Run From R.A.P.,” which features cameos from 2 Chainz and Ty Dolla Sign. His label encouraged him to jump onto the service after LeBron James touted him as a favorite new act.

“It’s a great service, I love it, but with any new service, they always need that cool,” Symba said. “Clubhouse needed to get people to be a part of it, and we provided that cool. If hip-hop wasn’t on there, no one would care. It would fade away.”

While the hip-hop and tech worlds have had wildly successful partnerships (Dr. Dre’s sale of Beats Electronics to Apple made him one of the richest figures in music history), Clubhouse wasn’t the most obvious fit at first. A lot of the early forums attracted the kind of San Francisco man currently trading his North Face pullover for a Panama hat on the crypto-friendly badlands of Miami. Investors valued it at $100 million this spring when it only had 1,500 active users.

The ephemeral nature of the chats — there are no transcripts or recordings, and if you miss a session, you’re out of luck unless you happened to record it elsewhere — made it less risky to speak your mind. Although it started as an in-group service for tech, the app, co-founded by Paul Davison, whose social app Highlight was acquired by Pinterest in 2016, and former Google engineer Rohan Seth, made a purposeful push for Black influencers over the summer. That includes a lot more than hip-hop — actor-comedian Tiffany Haddish and designer Virgil Abloh are lively regulars — but rappers undeniably helped made it popular. Davison and Seth did not respond to requests for interviews.

Clubhouse’s chief investor Andreessen Horowitz had previously funded the lyrics site Genius (formerly Rap Genius) in 2012, and that firm’s co-founder Ben Horowitz appeared with Nas at South by Southwest in 2014, visibly beaming to share a stage with a favorite MC. (Representatives for the firm declined an interview request).

Rappers and industry pros who dabble in tech investments took to Clubhouse immediately. Last month, Roc Nation hosted a party for Jay-Z’s birthday, where reams of executives, DJs and artists swapped stories from his decades-long career. On Dec. 14, Diddy hosted a chat timed to his techno-influenced “Last Train to Paris” album’s 10-year anniversary, where he dished on his career with the Notorious B.I.G.

“That even playing field has been valuable to hip-hop specifically. Because everything’s taken a hit during COVID-19, and that oral history of hip-hop is part of why I’m on there,” culture writer Vaughn said.

While new members had to be invited by users, keys to the app quickly spread among the Black music world. Already, the proximity to stardom has vaulted some careers.

In late November, the 20-year-old producer Loudy Luna jumped into a room on a Sunday night to play her new productions to a room full of digital strangers. She’d had some early looks in the industry — Lil Uzi Vert and Future used one of her beats for their track “Sleeping on the Floor.” But that night, she was still pretty unknown to most tuning in.

But her audience that night included Drake, 21 Savage and heavyweight producers Boi-1da and No I.D. She played her works in progress — spooky, seasick trap — to acclaim in the live chat. After the show, Drake direct-messaged her to swap info, and the two are now collaborating.

“It was crazy, Drake didn’t come in until halfway through and I couldn’t believe I was doing this in front of him. He popped in as ‘The Boy’ and I had to click to make sure it was really him,” Luna said. “You never know who you’re in a room with, and a lot of huge people don’t have all that many followers yet. I think that’s what makes people want to go on and play stuff, there are bigger people on there than you can imagine.”

But as Clubhouse hits a billion-dollar valuation in less than a year, it’s also clear the app is not a pristine walled garden.

For now, the exclusivity of the app has kept out a lot of the wanton, anonymous white supremacy and conspiracy culture that’s poisoned Facebook and other services. But the service’s steep ascent annoyed some in the rap world, who see eye-watering valuations built off their engagement.

“We were able to get our culture to embrace his product,” Master P said. “So we’ve got to exercise that same power, because we have it now. Our culture helped create this brand, so for phase two, let’s figure out how to put that money back into our community.”

Clubhouse, in a statement announcing its latest investment round, said that “Creators are the lifeblood of Clubhouse…Over the next few months, we plan to launch our first tests to allow creators to get paid directly — through features like tipping, tickets or subscriptions. We will also be using a portion of the new funding round to roll out a Creator Grant Program to support emerging Clubhouse creators.”

But the service itself can be volatile too. Some members, hoping for viral infamy, start antagonistic forums like “Did Pop Smoke Get Himself Killed?” The proximity to celebrity comes with its own risks. Tory Lanez, the artist accused of shooting Megan Thee Stallion, got an invite to the service from rapper Tyga, and his defenders are known to go after Black women who criticize him. Russell Simmons, the Def Jam co-founder who was accused of rape, is also an active user, as is Rihanna’s assailant Chris Brown. (Simmons has denied rape allegations brought by multiple women.)

In 2020, Megan Thee Stallion clocked two smash hits, advocated for Black women on ‘SNL’ and got four Grammy nods. She also survived a shooting and its aftermath.

In October, Drew Dixon, who accused Simmons of raping her in the HBO documentary “On the Record,” wrote, “I’m so grateful to friends who just warned me that @joinClubhouse may no longer be a safe space for me. Do you #ProtectBlackWomen or not so much?”

“There’s a lot of harm too and I don’t feel like it’s as addressed as it could be on the app,” Vaughn said. A firmer hand on moderation and prioritizing the needs and safety of users of color should be a much bigger priority. “There’s a lot of misogynoir, racism and transphobia, and white VCs and tech people can get up in arms about the influx of Black people onto the app. But Black people are what makes it popping.”

“At a minimum,” Bent agreed, “startups need to be involved in these conversations now. They all need to be invested in moderation. It’s hard to turn around Facebook or Twitter at this scale, so the new apps bear an even greater responsibility to figure it out.”

As the pandemic keeps rap fans, like everyone else, shut in at home, Clubhouse is the most compelling place to keep tabs and make a name without shows. TikTok drives hits, but Clubhouse meets a different need. If it’s really worth $1 billion right now, it’s all the more important to figure out how to preserve the community that helped make it valuable.

“We’ve got to start thinking about us waking up and knowing we can do these things for ourselves,” Master P said. “We just built a multi-billion dollar company. Paul Davison may be a genius, but we don’t know him.”

TikTok has become the single most important platform for generating new pop-music hits. But can it help mint stars, or just one-hit wonders?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.