How Mary Wilson and the Supremes changed the way America viewed Black music

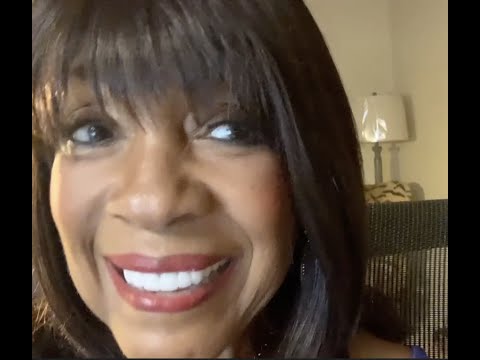

In a video posted Saturday on YouTube, Mary Wilson — the singer and style icon whose work as a founding member of the Supremes helped set the template for the modern pop girl group — looks like her excitement might lift her right out of her seat next to a fireplace in her home near Las Vegas.

“This month is Black History Month,” she says, “and just so much is happening.”

Smiling broadly, her eyes aglow as she peers into a camera held only inches from her face, Wilson tells viewers that she’s struck a deal to release a long-shelved solo record she made in the late 1970s with Elton John’s producer, Gus Dudgeon; she adds that she’s recorded some “surprising new songs” that she hopes to have out by her birthday on March 6.

Then, with no less enthusiasm, she runs through a series of significant Supremes moments in February’s past, including the release of “Run, Run, Run” on Feb. 7, 1964.

“We really thought that was gonna be a hit, but it wasn’t,” she recalls, grin still beaming. “But anyway …”

On Monday night, just two days after this video appeared, Wilson died suddenly of an unspecified cause, cutting short a career that the singer at age 76 clearly regarded as unfinished.

Her dedication to the Supremes until the very end of her life says plenty about Wilson’s role as the group’s linchpin: the essential element that held together the glamorous Diana Ross and the earthy Florence Ballard during the Motown trio’s mid-’60s heyday, and the woman who kept the Supremes alive for nearly a decade after both her original bandmates had departed.

In a statement, Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. called Wilson “a trailblazer” and said that “over the years [she] continued to work hard to boost the legacy of the Supremes.”

How could she not? Beginning with their first No. 1 single, 1964’s “Where Did Our Love Go” — which according to legend was devised with Wilson in mind as lead vocalist — the Supremes quickly set out on one of the most impressive runs in pop history, racking up 11 more chart-toppers by the end of 1969, shortly before Ross quit to become a solo act. (Among groups, only the Beatles have more No. 1s.)

Of Wilson, Patti LaBelle said on Twitter that “what she contributed to the world cannot be overstated,” while Dionne Warwick said she’ll miss her “radiant smile and energy she possessed.”

Diana Ross, Patti LaBelle and Gloria Gaynor are among the legendary musicians honoring Mary Wilson, an original Supremes member who died Monday at 76.

Today the Supremes’ hits — most written and produced by the peerless three-man team known as Holland-Dozier-Holland — have become an indelible part of American history, with plink-plonking rhythms that conjure the forward-march optimism of an era when youth felt like a new discovery.

Full of crisp harmonies and intricate vocal counterpoint, tunes like “Baby Love,” “Come See About Me” and “Stop! In the Name of Love” handled themes of young romance with a sophistication to match the women’s signature tailored gowns; the songs (and the look) challenged white listeners’ ideas about Black music, blurring cultural lines in a way that softened the ground for long-awaited political change.

Yet the music also throbbed with pure emotion: “My world is empty without you, babe,” Ross sang, backed by Wilson and Ballard’s ghostly ooohs, with haunting dejection. “You don’t really need me, but you keep me hanging on,” went another.

In “I Hear a Symphony,” which Wilson said was one of her favorite Supremes songs, the women describe the “tender melody” they hear whenever a lover is near — and the trick of the song, of course, is that the tune sounds just like this.

Ross’ leaving slowed the Supremes’ commercial momentum, not to mention the artistic coherence of a group that had been born out of adolescent friendships in a Detroit housing project. (Ballard, who’d been replaced by Cindy Birdsong in 1967, died in 1976.) But with a series of new recruits that over the years included Jean Terrell, Scherrie Payne and Susaye Greene, Wilson hit some high points as the Supremes experimented throughout the ’70s; there’s a trippy rendition of Joni Mitchell’s “All I Want,” for instance, that the group recorded with Jimmy Webb, who keeps trying to turn the song into “Up, Up and Away” by the Fifth Dimension.

For all her investment in the Supremes (who finally broke up in 1977), Wilson was hardly pie-in-the-sky about the group’s problems. In 1986 she wrote frankly in the first of her several memoirs about Ross’ ambition — “If you happened to be in her way while she was going toward the center, that was your fault” — and about her unhappy financial dealings with Gordy; she called the book “Dreamgirl” in winking acknowledgment of the drama-filled Broadway musical “Dreamgirls,” which fictionalized the Supremes’ story.

Carole King left her life in New York for L.A., and with the support of friends like James Taylor wrote “Tapestry,” one of the best-loved albums ever.

Nor did her success as a member of a so-called crossover act inure her to the racial injustice that still infects so much of American life.

When I called Wilson last summer to hear her thoughts for a story I was writing about the legacy of Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” she advised against thinking of the famous 1971 protest album as a strict disavowal of Motown’s traditional emphasis on love songs.

“As Black people, we all wanted to be happy,” she said. “We all liked singing love songs. But there comes a time after that, after the Martin Luther King, when you need a Malcolm X.”

Wilson launched her solo career in 1979 with a self-titled LP whose cool reception goes some way toward explaining why the record with Dudgeon never came out. (“Red Hot,” the debut’s lead single, is a breathy disco jam that deserved slightly better than its No. 95 showing on Billboard’s R&B chart.) But though she wouldn’t put out another album until “Walk the Line” in 1992, she went on to perform steadily in concert halls and cabarets; she also became an activist involved in women’s health and in efforts to modernize copyright law.

And, of course, her influence as a Supreme was readily apparent in the work of successive generations of girl groups including En Vogue, TLC, Destiny’s Child and Fifth Harmony.

You could hear it in those acts’ music — in the tight harmonies and the lyrics about the pleasures and torments of love. You could see it too in the younger musicians’ cleverly coordinated, occasionally eye-popping outfits.

“They remind me of myself,” Little Richard said of the Supremes when he inducted the trio into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988. “They dress like me.”

In 2019 Wilson published her fourth book, “Supreme Glamour,” a coffee-table volume detailing many of the Supremes’ most memorable looks. It was one more instance of her careful stewardship of an enduring pop phenomenon.

“Our glamour changed things,” she told the New York Times that year. “We were role models. What we wore mattered.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.