Appreciation: Wry and worldly, warm and welcoming, Tom T. Hall was a songwriter’s songwriter

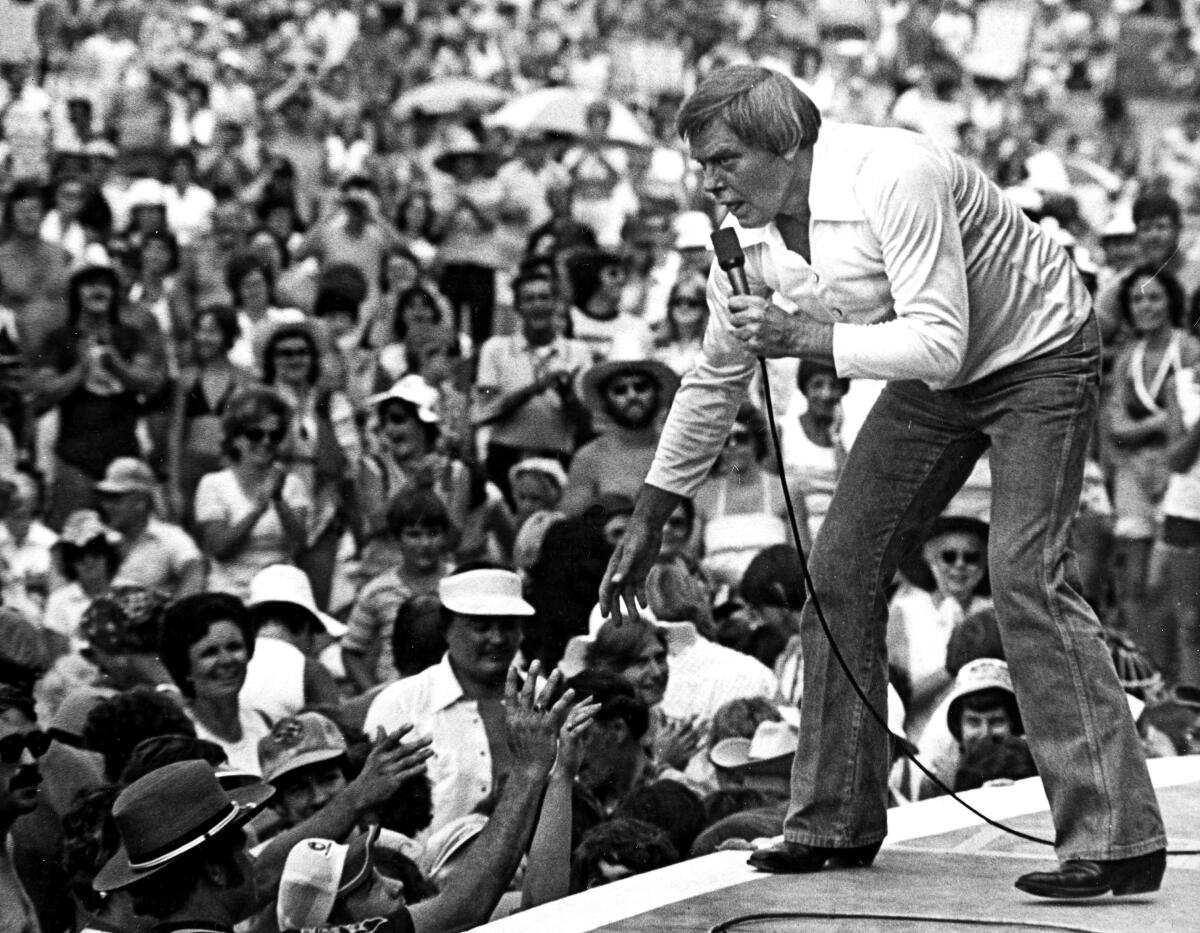

Singer-songwriter Tom T. Hall was known as “the Storyteller,” a nickname that suited his literary gifts even if it didn’t quite encompass the scope of his talents.

Longtime friend and peer Bobby Bare once said, “Tom T. would have made a great writer for movies, because he knows how to put words in people’s mouths that you believe.” After learning that Hall had died Friday at his home in Franklin, Tenn., at age 85, alt-country artist Jason Isbell wrote on Twitter, “The simplest words that told the most complicated stories. Felt like Tom T. just caught the songs as they floated by, but I know he carved them out of rock.”

Indeed, Hall was compared as often to famed short story writers as he was to his fellow tunesmiths: Rock critic Robert Christgau called him “a cross between Chekhov and O. Henry.” Despite “the Storyteller” moniker, however, Hall didn’t write conventional story songs with clear narratives. Instead, he sketched out scenarios and recounted interior monologues, creating a vivid sense of time and place through his finely rendered details.

Fittingly, Hall’s work reflects his era, when old-fashioned country values collided with the turbulent modern world of the 1960s and ‘70s. Hall wasn’t part of the counterculture, but his perspective was wry and worldly, bearing weathered wisdom rivaled only by fellow singer-songwriting giants Kris Kristofferson and Merle Haggard. Where the Bakersfield-based Haggard stood outside of Nashville, Hall was part of the Music City, working with Nashville’s elite session musicians on his own records and building his reputation by writing tunes for other artists.

At the start of his recording career, many of Hall’s best songs wound up being popularized by other singers; as a matter of practice, he wouldn’t record his own versions of these tunes. Chief among these compositions was “Harper Valley P.T.A.,” the smash from Jeannie C. Riley that hit the cultural zeitgeist in 1968. Riley’s snarl gives the record a kick but it’s the series of character sketches rendered by Hall that gave the song its power: within a few lines, he captured a small town filled with duplicitous hypocrites. The song isn’t told in the first person; the narrator is remembering how a single mother in a miniskirt chewed out the PTA for her behavior. It’s one of the narrative tricks Hall would return to throughout his career, allowing him to tackle such controversial topics as women’s liberation from a safe distance.

Hall did mine his personal life for inspiration. “Ballad of Forty Dollars,” which gave him his first Country Top Ten hit in 1968, came from his short time as a gravedigger. The narrator stands apart from the group watching the funeral proceed, admiring a shiny limousine and the widow (“That sure is a pretty dress / You know some women do look good in black”), coming to the conclusion, “I hope he rests in peace, the trouble is the fellow owes me forty bucks.”

Hall had a knack for delivering unexpected punches, as he did on “Homecoming,” the tale of a country singer visiting his widowed father after being “gone so many years, I didn’t realize you had a phone.” Hall paints a full portrait of a selfish singer through his series of excuses and equivocations; he’s hung by his own words.

“Homecoming” is as cold and flinty a character study as anything by Randy Newman, yet it’s a bit of an outlier in Hall’s discography. “A Week in a Country Jail,” the song that gave him his first No. 1 single in 1969, is a better touchstone, pushing his sense of humor to the forefront, relying on his offhand, casual delivery and set to a rolling rhythm vaguely reminiscent of bluegrass. It’s a warm, welcoming sound that Hall would develop over the course of the 1970s, gradually softening his music so much he wound up with a pop crossover hit with 1973’s singsong “I Love.”

Fittingly for a native of Kentucky, bluegrass was at the foundation of Hall’s music. His first band was a bluegrass outfit called the Kentucky Travelers, which he led while he was a teenager in the early 1950s. After he became a star in the 1970s, he returned to bluegrass for “Magnificent Music Machine,” an album recorded in collaboration with Bill Monroe, and he recorded “The Storyteller and the Banjo Man” with Earl Scruggs in 1982.

Hall was inducted into the International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame in 2018 alongside his wife, Dixie, but it’s the music that he made during the late 1960s and 1970s that endures. Hall’s character sketches on “The Year That Clayton Delaney Died” and “Old Dogs, Children and Watermelon Wine” are imbued with humanity and wit, while his easy fusion of country, bluegrass, Dixieland and pop pointed the way toward the Americana music of the 21st century.

Some musicians immediately picked up on this genre-bending. Country-rock pioneer Gram Parsons covered Hall’s “I Can’t Dance” on his 1974 album “Grievous Angel,” and “That’s How I Got to Memphis,” a Hall song Bobby Bare had a hit with in 1970, became a standard covered by Lee Hazlewood, Rosanne Cash, Buddy Miller, Solomon Burke and the Avett Brothers over the years.

Hall’s music endured even though he essentially retired after 1985’s “Song in a Seashell.” A decade later, he had a brief revival, releasing two albums — “Songs From Sopchoppy” in 1996, “Home Grown” in 1997 — on Mercury Records. Alan Jackson recorded Hall’s “Little Bitty” from “Songs From Sopchoppy,” giving him his last No. 1 hit as a songwriter in 1996. The Tom T. renaissance continued when Hall was the subject of a 1998 tribute album, “Real,” that featured artists such as Johnny Cash, Iris Dement and Whiskeytown.

Hall was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2008 and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2019. Upon his induction to the Songwriters Hall of Fame, Hall reflected, “I was listening to the radio one day, and somebody said, ‘That sounds like a Tom T. Hall song,’ I said, ‘I must be doing something a little different than everybody else because now there’s such a thing as a Tom T. Hall song, and I’m going to buy into that.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.