How a trans indie-rock star made the record of their life, with the help of some new housemates

Last year Meg Duffy, who performs as Hand Habits and uses they/them pronouns, was given a pair of gold earrings that sent a jolt of energy through their system and helped birth a song called “Gold/Rust.”

They belonged to Duffy’s late mother and were the first objects of hers that the guitarist, who until recently was better known for their work with the War on Drugs, Kevin Morby and Weyes Blood, had held in decades.

Duffy, 31, started pondering the talismans while living at the Log Mansion, the Mount Washington home and studio overlooking the Arroyo Seco that since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic they’ve shared with the artists Sasami Ashworth, 31, and Kyle “King Tuff” Thomas, 38. A year earlier in an Instagram post, Duffy had offered a revelatory, and rare, snapshot of their early life: “It’s my mothers birthday she passed away when i was 4 and basically everything i do is a response to the void.”

Like Hand Habits’ surprisingly buoyant new album, “Fun House,” the post typified the depths Duffy had been traveling to understand the foundations of their identity — and the distance that remains. They also address their mom in “Aquamarine,” another song on “Fun House.” “I didn’t know she played guitar ‘til I turned 27,” sings Duffy, adding a few verses later, “I never ask for details / Who the hell needs details? / When everything is burning / You light a fire on the grave.”

An upbeat, expertly arranged exploration of questions that weigh a ton, Duffy’s Ashworth-produced, pop-adjacent album is Hand Habits’ most accomplished and adventurous so far.

“Not to be overly mystical about this, but it all seemed really fated,” says Duffy, who wears their hair in a shaggy “Revolver”-era Beatles bob. “I wanted to live in a house with people I felt comfortable with. Then the whole world shut down — but there’s a studio here and these are the only people I’m seeing every day.” They had planned to record “Fun House” outside of Los Angeles, “but then it just started to become painfully obvious. Why would I do it anywhere else when the energy in this house is so creative and everybody’s always making music?”

At it happened — Thomas calls it “a funny alignment” — Ashworth and Thomas had their own high-profile studio albums coming due when the coronavirus hit. So, fueled by what Ashworth calls Duffy’s lunchtime “spiritually engaged salads,” they recorded all three at the Log Mansion during the pandemic. Sasami’s heavy, distorted rock album, “Squeeze,” comes out via Domino early next year.

Ashworth calls her album the “darker sister” of “Fun House” — “Meg’s like the little angel emoji and I’m like the little devil emoji.” And though not announced yet, King Tuff’s forthcoming album will come out via indie powerhouse Sub Pop sometime in 2022.

“There’s no way any of these records would exist without the other records. They’re all very intrinsically linked, and that was a big part of being in the house together,” Ashworth says on a recent weekday while sitting next to Duffy at a picnic table beside their home. A few feet away, an ash-filled fire pit offers evidence of nights spent under the stars.

King Tuff’s Thomas moved into the two-story Craftsman-style house about five years ago. Although mere blocks from the busy Figueroa Street and surrounded by houses on all sides, the 1909 bungalow is barely visible from the steeply graded sidewalk about 50 yards away. It earned its moniker after Thomas built a recording studio in a back bedroom.

The musicians have survived the current plague through a strategy Duffy calls “positive distraction from the perils of the burning world.” Directing their gaze at Ashworth, Duffy adds that in addition to learning about process from her and Thomas, they “lit a fire under my ass. You guys are always making music. It was so intoxicating.”

Amid reforms in the Grammy nomination process, Olivia Rodrigo and Lil Nas X are considered early favorites. But a (very) old-school album could steal the show.

A classically trained French horn player, Ashworth dropped out of Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., about a decade ago and moved back to Los Angeles, where she was born and raised. She set the horn aside for keyboards and started making inroads in the Northeast L.A. music scene.

Duffy had recently ended a relationship and was touring Australia as guitarist for Perfume Genius when COVID-19 hit. After returning to the U.S. and staying in North Carolina for a few months, they headed back to L.A. During a chance thrift-store encounter, Duffy told Thomas they were looking for a new living arrangement. Duffy moved into the Log Mansion’s first-floor bedroom not long after.

By then, they needed a break. Born in upstate New York, Duffy received their first attention as the long-haired guitarist in folk rock singer-songwriter Morby’s band. Duffy’s Hand Habits moniker was born the same year, 2017, that their slide-guitar melodies on two War on Drugs’ songs propelled their sound into the mainstream. Duffy has become an accomplished session guitarist, having appeared on records by Vagabon, Fruit Bats and Sylvan Esso.

As they settled into a routine at the Log Mansion, Duffy resolved to explore the biggest mystery of their life, the suicide of their mother when Duffy was 4, both through therapy and introspection. “She had really bad post-partum. It was the ‘90s and mental health was still a struggle.” In the aftermath, Duffy was raised by a few different family members but grew up with this gaping hole. “I didn’t have a lot of information, and I didn’t have a lot of context for myself as somebody’s child. I always had ideas or fantasies — and some memories, but memory changes over time, and the void becomes a kind of context.”

Duffy started emailing a cousin who knew their mom, and soon received a box of things belonging to her. Among them were the earrings. “It’s the only object of my mother’s that I have that I know that she touched. And then hearing that she played guitar, that she was often smiling and she also had a really dark side — it was so informative.”

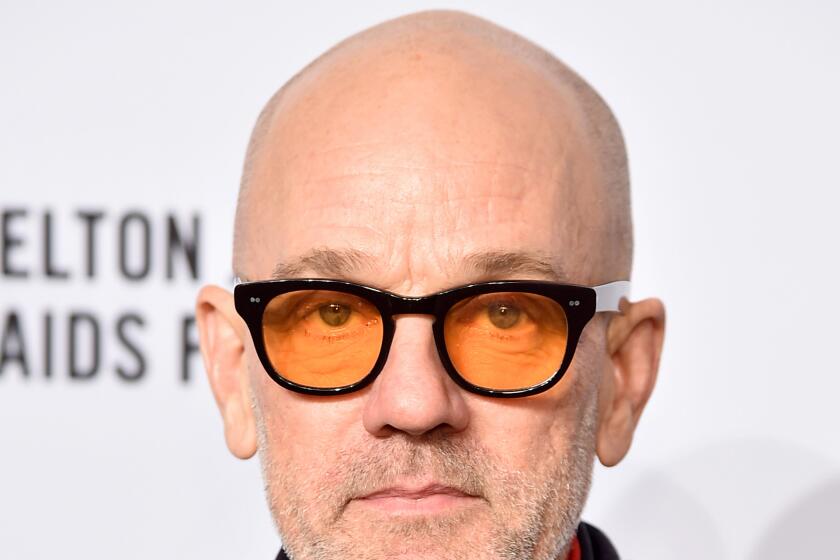

Lifelong Velvet Underground fan Michael Stipe on discovering ‘Loaded’ on an 8-track tape, his friendship with Lou Reed and the pleasures of out-of-tune singing.

As they were working through those emotions, early in the pandemic on Trans Visibility Day, Duffy wrote a message on Instagram that, while notable, they hadn’t exactly been hiding: “i don’t know who needs to hear this but apparently it’s trans day of visibility i’ve been taking hormones for 8 months i am learning but tbh we are always visible y’all.”

Asked about the decision to publicly acknowledge their transgender identity, Duffy clarified. “My family is always like, ‘So you’re trans. Do you want to be a man?’ To be honest with you, I don’t know. It’s not as cut-and-dried for me.” Duffy says they began hormone treatments about two years ago. While they haven’t wanted to make a big deal of it, they nonetheless understand the importance of trans visibility. “Time and time again when I think my identity doesn’t matter, some 16-year-old trans person is like, ‘Thank you for being out.’”

The “Fun House” demos that Duffy presented Ashworth barely resemble the finished product. Offered skeletal, relatively slow-paced versions composed on guitar, Sasami accepted the bones and started adding flesh. Originally funereal, the first move Ashworth made was increasing tempos — while adding richly textured acoustic and electronic arrangements that firmly pushed the songs toward contemporary pop.

The producer’s polished first draft, Duffy says, caused equal parts shock and epiphany. “I never really realized how much I was boxing myself in, basically out of fear and that imposter-syndrome feeling,” Duffy says.

“For me the metaphor is, Meg is parallel parking and thinks that there’s no more space,” says Ashworth. “I’m like, ‘Keep coming, you’re good!’”

Ashworth has also produced for Thomas’ King Tuff project, he says on the phone from Vermont, where he’s working with his longtime bandmate in the stoner rock band Witch, J Mascis of Dinosaur Jr. Thomas calls Ashworth “an incredible producer. She can hear a song and instantly hear how the arrangement should go.”

Songs on “Fun House” transform universal questions — the refrain for “Aquamarine” is, simply, “Who am I?” which they rhyme with “suicide” — about character, history, repressed emotions and identity into sophisticated explorations of contemporary pop, while remaining immediately identifiable as Hand Habit songs. Lyrics plumb Duffy’s quest: “How can you separate the blood from within?” “The plot is lost.” “My body, a question that hangs on her tongue.” “There is nothing left for you — two earrings are not proof.”

The night before the “Fun House” release, Duffy called to offer a few more thoughts. They were busy tie-dying T-shirts for the Hand Habits release show at the Pico Union Project and had just finished rehearsing for the first live performance of the new songs. With life returning to a semi-normal state, Duffy will embark on a brief West Coast solo tour starting in November, but they’ll be keeping their room at the Log Mansion.

Water sloshed as they dipped knotted shirts and talked about performing again. “That’s when I talk to God,” says Duffy. “It’s the closest that I can get to disappearing that’s not toxic.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.