Newsletter: We finally got a look at Joan Didion’s potato masher of manifest destiny

Aaaand we’re back. It’s 2022, yet it feels like 2021 and 2020, thanks to that continuous spiral known as the COVID-19 pandemic. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and urban design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and I’m here to break up the monotony with arts news, green juice and potato talk.

A most humble literary device

The holidays were marked by the loss of too many prominent cultural figures. Particularly seismic was the death of Joan Didion at the age of 87. In an obituary whose thoughtful writing is truly worthy of its subject, former Times staff writer Elaine Woo describes an “unsentimental chronicler” who “deployed trenchant facts like surgical bombs.”

Of course, her influence on other writers was legion — among them: me. I’m no Didion — my style is more Latin American churrigueresque meets saucy newspaper gal — but I have long been inspired by the ways in which Didion pulled at the threads of established narratives until there was nothing left but a tangled heap. In an appreciation I wrote of the author, I looked at how she used the story of a family potato masher, which had made the grueling trek West during the 19th century, as a literary device with which to unravel myths about rugged individualism.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

My curiosity, naturally, got the best of me, and I decided to track down the masher.

It resides in the archives of Pacific University in Forest Grove, Ore., where it was donated by a relative of Didion’s in the 1950s. A university archivist was able to locate a listing for it, but by the time I reached out in the wake of Didion’s death on Dec. 23, the university had closed for the holidays. An image would not be forthcoming. The masher remained in the literary realm.

Well, the holidays have passed, and campus has reopened. And this week, I was delighted to receive an email from Emily Johns, a cultural resources assistant at Pacific University, who confirmed that Didion’s ancestral masher indeed remains in their collection. She also attached some pictures.

And there it was: a simple wooden masher, looking nothing like I’d anticipated. (My expectations had been shaped by the steel mashers of the 20th century.)

Johns was an all-too-willing partner in my rather quixotic hunt for the object I had taken to calling “the masher of manifest destiny.” But there is something poignant about an object and the narratives with which we imbue them. (I grew up Catholic; it’s all about the relic.)

When she started poking around the archives, Johns had no knowledge of the masher’s connection to Didion or its multiple appearances in her 2003 book “Where I Was From.” But my obsession ultimately became hers. “I found it exhilarating when I finally opened the right box and realized that I found it,” she tells me via email.

She says the whole episode gives her a profound appreciation for her job: preserving objects, but also the stories that surround them. “How many other objects in our museum storage have unique stories and connections that are waiting to be discovered?”

Didion told us some of those stories. She also told us about all the ways in which those could all too easily veer into myth.

Remembering the Jan. 6 insurrection

It couldn’t be a more propitious time to reflect on the ways in which myth can shape politics and society. This week marked the first anniversary of the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. The Times’ White House correspondent Chris Megerian examines the ways in which the lies that fueled the insurrection — the fictional notion that the election was stolen — remain embedded in U.S. politics. “Instead of providing a foundation for national unity,” he writes, “Jan. 6 became a launchpad for disinformation and new state laws to restrict access to the ballot box.”

Photographer Kent Nishimura was in the crowd during the riot — and, at one point, was attacked by a man wielding a flagpole, who shouted at him that he was “fake news.” This week, he released the footage from the GoPro camera he had attached to his helmet. It’s chilling.

One of the images that most stuck with me last year was a photo taken by Nishimura in the wake of the attack that shows a group of National Guard members asleep inside the U.S. Capitol, its forms both graceful and tragic.

The attack on the Capitol, naturally, has begun to materialize in culture. Artist Andres Serrano has woven together hours of video footage from the attack into a feature-length film titled “Insurrection” that debuted this week in Washington, D.C. Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott describes a “linear but deliberately paced narrative highly dependent on music to underscore or deflate both the tragedy and absurdity of so much of what happened.”

Performance notes

Omicron is rattling the performing arts. The Times’ Christie D’Zurilla has been keeping a running list of pandemic-related cancellations across all areas of culture. And my colleague Jessica Gelt is reporting on how L.A. fine arts organizations are contending with the surge.

For now, many of the region’s largest performing arts organizations, including the L.A. Phil and Center Theatre Group, are moving ahead with concerts and shows in the coming days and weeks. But they are getting stricter about who gets in: Starting Jan. 17-18, these organizations will begin requiring evidence of booster shots.

Thankfully, some productions haven’t given up on the internet. Among them, Lynn Nottage’s new play, “Clyde‘s,” starring Uzo Aduba, which is on view IRL at the Hayes Theater in New York City — but also offers a livestream. Times theater critic Charles McNulty recently logged on to see the play, which he says catches Nottage in “a more relaxed, comic mode.” Set in a restaurant staffed by ex-cons, the play is “an entertaining battle between a diabolical capitalist who asks her staff to fry up putrid Chilean sea bass and an evangelist who preaches a gospel of dignified labor.”

Visual arts

Times art critic Christopher Knight reviews “Mixpantli: Space, Time, and the Indigenous Origins of Mexico,” a new group show at LACMA that wrests narratives about the Spanish conquest of Mexico from the Western point of view. “This time, it’s the conquered rather than the conquerors who are given the stage,” he writes. “The show means to look at how Indigenous people absorbed aspects of their vanquishers’ worldview into their own.”

The Orange County Museum of Art has announced a new acquisitions program to mark the museum’s 60th anniversary, reports The Times’ Deborah Vankin. The museum’s current male-to-female ratio is 75 to 25, says director Heidi Zuckerman. “So a big part of my initiative is to collect works by female artists. And, of course, artists of color.” This follows the appointments of Courtenay Finn as chief curator and Meagan Burger as director of learning and engagement. OCMA expects to open its new building, by Morphosis, this fall.

Design time

My curiosity piqued by an obituary I wrote about L.A. architect Bernard Judge in November, I paid a visit to his “Tree House” in the Hollywood Hills — a 1975 home that was shaped by the architect’s interest in building cost-effective housing that was also ecologically minded. Located off of a vertiginous road on the crest of a hill above West Hollywood, the house has some pretty staggering views.

Lisa Boone’s series on ADUs continues with a look at a 320-square-foot tiny home in a Santa Monica backyard designed by Minarc. The unit, known as the Plús Hús, is one of the more than 40 preapproved ADU designs available through the L.A. Department of Building and Safety. (I wrote about the launch of that program last spring.) The Plús Hús is also prefab — arriving on-site from a flat kit of parts that was assembled on-site in one day.

Essential happenings

Matt Cooper kicks off the new year with half a dozen weekend happenings, including gigs by Broadway crooner John Lloyd Young at the Catalina Jazz Club and an L.A. Phil concert led by Michael Tilson Thomas.

Cooper also rounds up all the latest museum exhibitions to see in L.A. and O.C. in January, including a show inspired by notions of mapping at the Huntington Library.

Plus, it’s your last chance to catch a couple of intriguing gallery shows:

At Cirrus Gallery in downtown, “Holy Squash: Jibz Cameron, Jackie Rines, Barbara T. Smith” brings together works by three L.A. artists exploring the fragility and power of women’s bodies. (Cameron’s drawings are electric, and I recently wrote about how much I appreciated the scans Smith made of her own hands.) And at Kayne Griffin in Mid-City, New York-based artist Hank Willis Thomas riffs on the nature of freedom and the flag — a timely bit of rumination on the anniversary of the insurrection.

Both shows have their final day on Saturday.

Passages

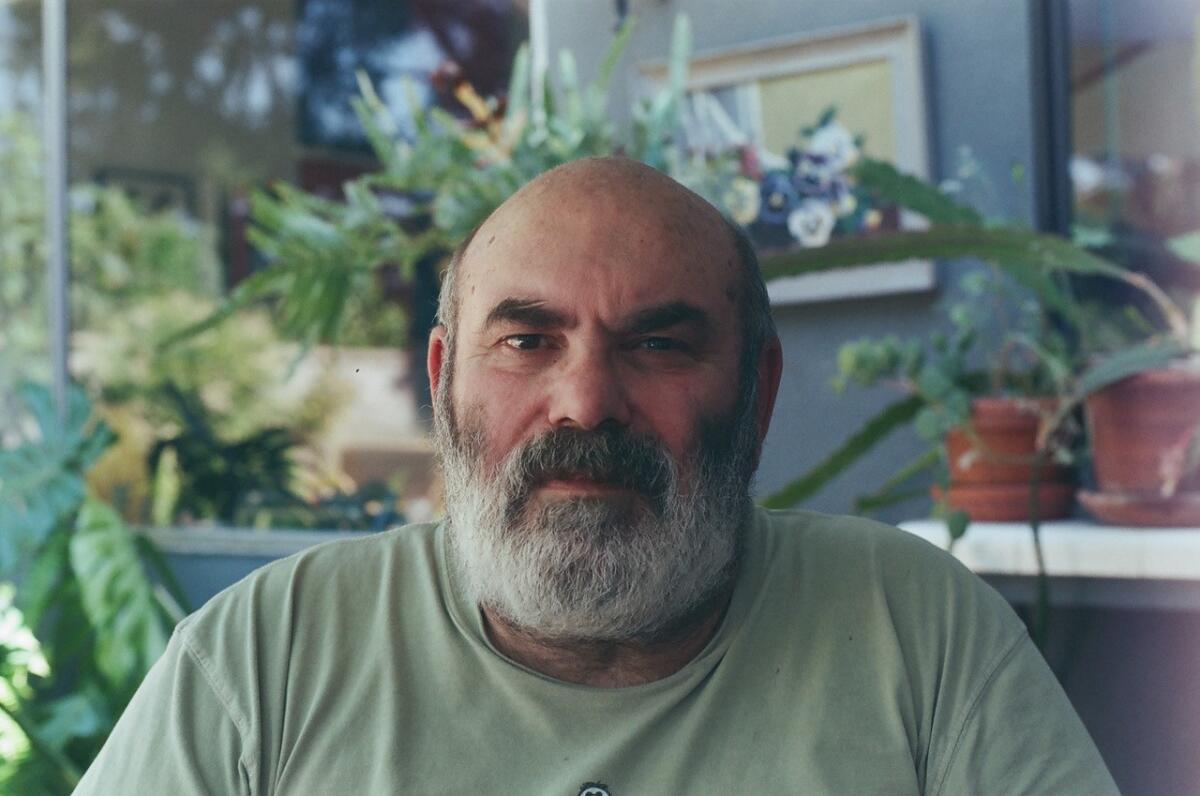

L.A. conceptual artist Luciano Perna has died at the age of 63; the cause, an apparent heart attack. In his obituary, Christopher Knight describes an artist “whose quirky sculptures and varied photographs play with the elasticity of matter and time, often concealing unexpected autobiographical depths.”

Harvey Evans, an actor, singer and dancer who landed roles in the original Broadway productions of “West Side Story,” “Hello, Dolly!” and “Gypsy,” is dead at 80.

The end of 2021 — so relentless a year — also claimed painter Wayne Thiebaud, architect Richard Rogers (of whom I wrote an appreciation) and the singular Los Angeles essayist Eve Babitz.

Arts contributor Christina Catherine Martinez wrote a moving tribute to Babitz: “I’d never read sentences like Eve’s — beautiful, breathless, full of information yet humming with the stress of running into a coked-out acquaintance at a party.” And Hunter Drohojowska-Philp had a very revealing chat with artist Ed Ruscha and his brother, Paul, about this most Los Angeles of writers.

Find more on Babitz’s estimable legacy here. And do not miss the Doors’ drummer, John Densmore, reminiscing about Babitz and Didion. Whoa.

Didion addendum

A lot was written about Joan Didion in the wake of her death. I was particularly intrigued by D.J. Waldie’s examination of Didion’s 1993 New Yorker essay about Lakewood. Waldie, of course, is from Lakewood, and it’s the city he so bracingly writes about in his 1996 book “Holy Land.” In his piece, he looks at what Didion examines, but also what she elides: “It seemed that my neighbors were still not agents of their own history, that someone from somewhere harder and colder would tell their stories for them.”

I’m also partial to Hilton Als’ poetic tribute in the New Yorker. “Developing a voice requires more than feeling outside of things, though,” he writes, “it requires strength, ingenuity, and the discipline to hear what other people are saying — and then to turn it inside out as you try to unravel the mystery underlying the meaning.”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Need to catch up on your Didion? Times editors Matt Brennan and Boris Kachka round up the essential books. And you can find a full slate of essays, excerpts and roundups published in The Times at this link.

In other news

— The New Yorker’s Parul Sehgal looks at the ways in which trauma is increasingly deployed as narrative device in books and in film.

— A terrible Missouri county logo will be redesigned after being relentlessly pilloried on social media.

— In New Orleans, artist Kevin Beasley took his artist commission fee from Prospect.5 and invested it in the Lower Ninth Ward.

— The Watts Towers are turning 100. The Times’ Chris Reynolds pens an ode to L.A.’s “most admired and least understood landmarks.”

— Historic streetlamps on the Glendale-Hyperion Viaduct have been going missing.

— Travis Diehl rounds up L.A.’s innovative art spaces in Art in America.

— Artists on DeviantArt say they are being plagued by plagiarized NFTs.

— “Virtual worlds, it seems, also train players to be eager, expectant, and constant consumers.” Anna Wiener on the metaverse is a great read.

From the book pile

I somehow managed to get some reading done over the holidays and wanted to share some finds:

First: Stop whatever you’re doing, and pick up Carribean Fragoza’s strange and wonderful and Goth-grotesque short story collection, “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You,” published by City Lights Books last year. I have marinated in so many of her dark and poetic lines: “It was that other me, the shadow me that I had never truly seen, except in glimpses in the corner of my eye, where they say your furtive death hides until it’s the right time.”

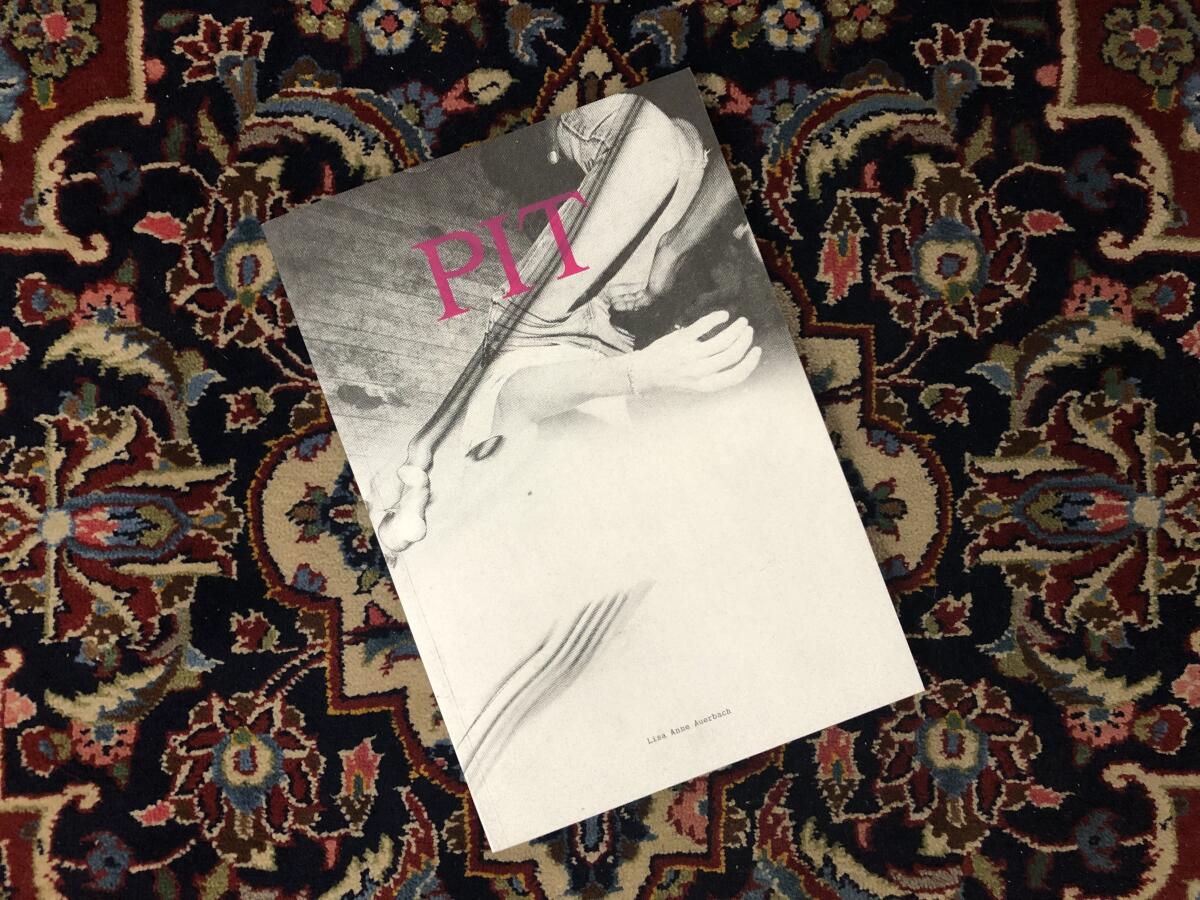

On the visual side, I have really been digging Lisa Anne Auerbach’s “Pit,” published by the independent U.K. press the Grass Is Green in the Fields for You. It’s a slender volume that gathers Auerbach’s images from punk mosh pits — photos that put the viewer right at the roiling heart of a ballet of naked aggression punctuated by flashes of youthful sensuality.

Photographer John Brian King released “Riviera: Photographs of Palm Springs” in 2020, and I’m sorry I’m just getting around to it now. The 112-page volume, published by Spurl Editions, features 99 color photographs of odd bits of cityscape and desolate pieces of landscape that feel like a far more honest visual assessment of the city than the glossy travel lens through which Palm Springs is so frequently rendered. It is rife with moments of sharp absurdity: the odd public monuments and majestic place names that don’t quite deliver on their glamorous promises. A keeper.

And last but not least ...

While poring over writer and photographer Janet Sternburg’s book “I’ve Been Walking,” published by Distanz last year, she says in an image what would take a writer thousands of characters to express. We are here, indeed.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.