Inquiring minds want to know: Who reads tabloids these days?

So there you are in the grocery checkout line, kicking yourself for forgetting the reusable bags and wondering why you didn’t just go through the self-checkout. And there they are.

The photos. The headlines.

“Back Together at Last! Brad & Jen: We want a BABY! ‘This Is Our Second Chance.’ Their secret IVF journey. Why they’re in no rush to get married. Moving into their old home!”

That is completely untrue, your rational mind says as you pick up the tabloid to kill the time. Brad and Jen were done years ago. As if they’d ever get back together. Wait, Jen’s 50 — could she still have a baby at 50? It must be nice to move back into your old house … and really, why would they get married again right now, so soon after both of them got divorced?

“Next!!,” the cashier shouts. You stuff the gossip rag back on the rack, hoping nobody noticed.

Now you really wish you’d gone through the self-checkout.

Such is the tabloid landscape populated by the National Enquirer and its stablemates the National Examiner and the Globe, which American Media Inc. announced in April would be sold to Hudson News Distributors, and the glossies Us Weekly, OK, Star, Closer, InTouch and Life & Style, which will stay with AMI.

Though their circulation has been decimated — the once-mighty National Enquirer, which approached 8 million in paid circulation at one point and reached millions more, is down under 180,000 as of June, according to industry monitor the Audit Bureau of Control — tabloids still occupy a unique place in American culture.

The National Enquirer’s mass-appeal magic came from publisher Generoso Pope Jr., said 20-year tabloid veteran John Isaac Jones, author of the 2014 book “Thanks, P.G.! Memoirs of a Tabloid Reporter.” Pope’s career is well chronicled in the documentary “Scandalous: The Untold Story of the National Enquirer,” which opened in November and is available on-demand via Amazon Prime and iTunes.

“It was the classic definition of kind of a lowbrow Reader’s Digest. Because he went for practical tips,” Jones said. “G.P., he read all the mail. ... He knew what kind of stories to play. And he was an absolute master at it.”

Now all the tabloids, to different degrees, aim for the same targets: stars, scandals and sex.

“The older people buy them. I sold two today, I think,” said Sonia, a checker at a Long Beach grocery store who didn’t want to give her last name. We’ll have to take her word for it, as many hours spent lurking in and around a half-dozen grocery stores yielded not one tabloid purchaser.

The National Enquirer’s advertising media kit, meanwhile, touts a median reader age of 50.6, a median reader household income of just under $60,000 a year and a total audience reach of 5.3 million.

Magazine sales, including the tabloids that arrive each Tuesday, are down 11% year-over-year at Ralphs, said John Votava, director of communications for the grocery chain. Still, that’s No. 3 in the general-merchandise category, after cigarettes and greeting cards. The celebrity publications sell for $5 or $6 a pop.

“You’ve got that impulse buy at the register,” Votava said. “People see that headline, they’re like, ‘Oh, this looks like fun, I could take this home and read this.’ ... I hope there’s not people who are reading it and believing it verbatim.”

Once a journal for the weird and wacky, tabloids have evolved to focus on celebrities, scandals and sex, though they include “service” stories as well — stories about arthritis or heart disease, for example.

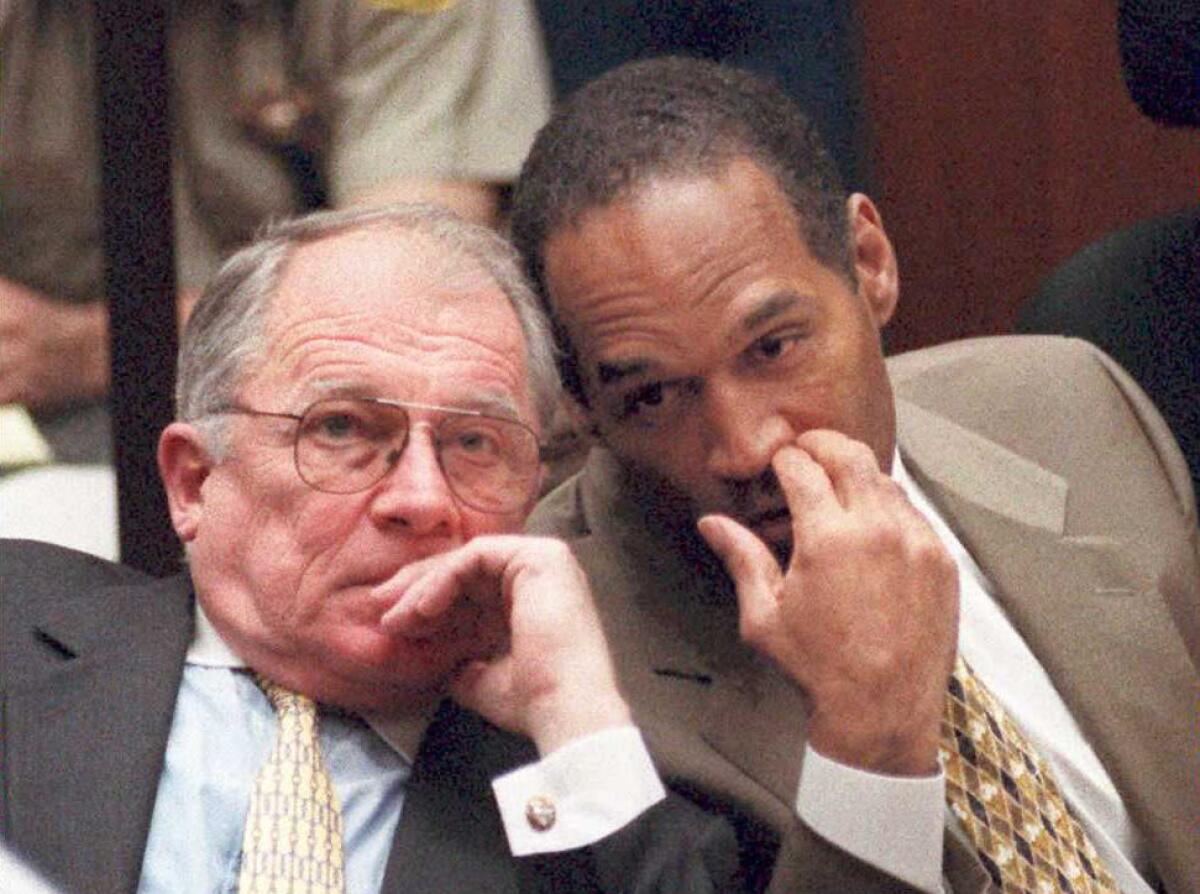

The industry turned in 1995, spurred by the cultural phenomenon that was the O.J. Simpson trial, according to former reporter Jones, now an author living in Florida.

“When everyone saw how popular O.J. was on television, everybody else jumped on the bandwagon,” he said.

Jones started working for the Enquirer in 1977, almost doubling the salary he was earning at an Alabama newspaper, with an essentially unlimited expense account. Those expenses would often include payoffs for tips and access, he said.

When he was trying to get to a dying Raymond Burr, whose partner Robert Benevides was at the actor’s deathbed trying to say goodbye, Jones paid his way from a gardener to a housekeeper and finally to a nurse who was caring for Burr. He bought the story from her.

While the last thing a mainstream journalist would do is pay for a story, Jones said, he’d “gotten a lot of stories that I paid for, [that] I would never have gotten them if I didn’t pay for them.”

Movie and TV sets also have been hotbeds for tips, according to Mary Murphy, an associate professor at USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

“People [on sets] would say, ‘They give you $100.’ I think that was the going rate for a tip,” said Murphy, who worked as a journalist for years at outlets including “Entertainment Tonight.”

But back to the O.J. trial, which Jones said gutted the value of celebrity dish. Now stars, scandals and sex — those sturdy tabloid staples — were being covered on TV, in magazines, in newspapers and even on the nightly news. And the internet was on the horizon.

“Everybody across the board saw how much the world loved scandal and drugs, sex, all the other accouterments that’s part of the tabloids,” he said. “Once the O.J. trial was over, it was the death knell for tabloids.” He left the business shortly thereafter.

But Murphy sees it differently.

The O.J. Simpson trial, during which the Enquirer tracked down photos of the star in Bruno Magli shoes he had denied he owned, “was the moment that those tabloids moved from just a supermarket checkout joke to ‘Hey, let’s pay attention to this,’” she said.

“I think it was a turning point, but I don’t think it was a turning point against. … Maybe not for their readership, their circulation, but for their reputation.”

“Scandalous” talks about how Enquirer reporters years ago found out about Bob Hope’s many extramarital affairs, but publisher Pope knew readers didn’t want to know that about a beloved star. So they killed the story in exchange for a half-dozen upbeat Hope exclusives, straight from the horse’s mouth.

It was an early incarnation of “catch and kill,” the practice where the tabloid gets a damaging story and decides not to run it — for a price.

More recently, “catch and kill” has come up with regard to women who had stories to tell about people like former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Harvey Weinstein and President Trump. Story rights were paid for and the tales were then shelved. David Pecker, CEO of American Media Inc. since 1999 and publisher of the Enquirer from then until it was sold to Hudson News Distributors in April, is close to Trump.

“The National Enquirer as it’s printed today is a very poor resemblance of the Enquirer of G.P.’s day,” John Isaac Jones said. “They have done the one thing that G.P. [who died in 1988] would never have allowed — that’s to inject politics into the Enquirer.”

Most tabloid fare these days is less nefarious than “catch and kill,” if similarly sketchy.

Stories run without bylines. Most sources are anonymous “insiders” or “pals” of the stars. A far-fetched plot will be put forth in great detail, with a short denial by a publicist slipped in where it won’t be noticed. Rivalries are built up between people who have little to do with one another, such as Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman, whose common denominators are acting and the college admissions scandal.

But celebrities and politicians are public figures, which makes it harder to sue for the types of stories that tabloids print, said Kavon Adli, an attorney with the Internet Law Group in Beverly Hills.

“If celebrities were to sue every tabloid that had a false story, it would become prohibitively expensive,” Adli said. Often stars simply trust that the public knows tabloids “have a reputation for sensationalism.”

But Jones, the former reporter, said the Enquirer never used to mess with the truth — or at least with the truth as told to its reporters. Interviews had to be recorded, and those recordings went through a fact-checking department.

These days, the tabloids are usually a step or two behind the rest of celebrity media, which can quickly push stories live online or on TV, unfettered by the slow nature of print production.

“California Wildfires: Hollywood Stars Run for Their Lives,” reads a story promo at the top of a recent National Enquirer. It’s about celebrities and the Getty fire, which threatened homes in Brentwood on Oct. 28, more than two weeks before the tabloid hit supermarket racks.

In comparison, outlets including People, TMZ and The Times had published similar stories the day of the fire, as people were actually fleeing the flames. The Enquirer’s website had nothing on the fire at all.

But a disconnect between a tabloid’s print product and its online presence isn’t odd. While most tabloids have websites, the content is rarely the same on both platforms.

“Most of the more outrageous claims are often reserved for the print editions,” said Andrew Shuster, editor of the fact-checking website Gossip Cop, via email.

The site investigates nearly every story in every tabloid, he said. Each story gets a rating, from zero (false) to 10 (true). There are a lot of zeroes.

“We do careful research and due diligence to avoid getting things wrong. Celebrity romances can be fickle, so if we say a couple hasn’t split and they split a month or two later, it doesn’t mean we were wrong at the time we said it, but things change,” Shuster said.

“But the reason we use a meter with a scale from zero to 10 is that not every tabloid story is so black-and-white. When there’s a gray area, we point out what is and isn’t accurate. Some stories are flat-out fabricated while others have kernels of truth, and we’ll acknowledge that.”

So what does the Gossip Cop team get tired of debunking?

“There are often recurring themes that have more in common with a bad soap opera than they do with journalism,” Shuster said. “Jennifer Aniston seems to be pregnant with Brad Pitt’s baby on a nearly weekly basis.”

Ugh. Remind us again, why didn’t we just use the self-checkout?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.