Appreciation: Brigid Berlin’s Polaroids chronicled Warhol’s world and presaged our social media age

Brigid Berlin was an artist who always rejected the label.

She snapped thousands of Polaroids of the denizens of Andy Warhol’s Factory studio in New York, where over the years she was also an employee — images that show a skilled hand in deploying unusual angles and the vulgarizing effects of the camera flash, not to mention double exposure.

For the record:

3:15 p.m. July 23, 2020An earlier version of this story stated that Brigid Berlin introduced Andy Warhol to Polaroid photography.

She regularly dabbled in performance in outré and outrageous ways. In the 1960s, Berlin appeared in a series of live bits in which she dialed people she knew from a stage and amplified their responses without their knowledge — say, while asking a friend for $100 to get an abortion. On several occasions, she appeared in Warhol’s experimental films, including 1966’s “Chelsea Girls,” where she can be seen talking on the phone and shooting up amphetamines.

And she wielded her own body as artistic implement. Berlin made paintings with her breasts (“Tit Prints”) and her overweight form regularly materialized naked and confident in photographs — one boob dangling out of her shirt in the famous 1969 photo of Factory regulars by Richard Avedon — at a time when Twiggy was the mainstream’s beauty ideal.

Altogether, Berlin’s work was prescient of our age of body positivity and of that social media compulsion to record our most trivial encounters. Yet she consistently refused to be described as an artist — even after Reel Art Press published a collection of her photographs, “Brigid Berlin: Polaroids,” in 2015.

“I want to get one thing straight: I am not an artist!” she told the Wall Street Journal at the time. “I’ve always liked art supplies better than art.”

Vincent Fremont, who first met Berlin in 1969 and began managing Warhol’s studio in the 1970s, later serving as one of the founding directors of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, says he never understood why she resisted the moniker.

“She hung out with all the artists,” he says. “She thought like an artist.”

At Max’s Kansas City, the nightclub and restaurant that was the boozy hangout of choice for old Abstract Expressionists (who took to the front room) and the rising Pop Art stars of the ’60s and ’70s (who hung in the back), “She hung out with the heavies in the front room,” says Fremont. “She was one of the few women involved with male artists — and not as a groupie. She was considered one of them.”

Likewise, her relationship with Warhol was not that of acolyte but of peer.

Guadalupe Rosales brings together fellow artists Nao Bustamante, Rafa Esparza, MPA and Zackary Drucker for video art screening online Sunday for LAND.

“She was the only one who could yell at him,” adds Fremont. “They were like a married couple but they weren’t married.”

Berlin died on Friday afternoon from cardiac arrest at NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City. Her death was confirmed by Fremont and Tony Nourmand, the founder and editor-in-chief of Reel Art Press. She was 80 years old.

Unlike Warhol, Berlin never became a household name. But she remains legendary in cultural circles for the ease with which she traveled across social circles as well as her outsize persona — one that was partly fueled by amphetamines.

“In the eighties, half my friends emulated one of 3 Warhol Superstars: Nico, Viva!, or Brigid Berlin!,” filmmaker and photographer Bruce LaBruce Tweeted in tribute on Monday morning. “Or sometimes combined aspects of all 3!”

Berlin also was renowned for her piercing wit, which was deployed with fearsome dexterity. As Pat Hackett, who edited Warhol’s diaries, told the New York Times: “Andy used to say, ‘If you ever want to learn what’s wrong with you, don’t look in the mirror; give Brigid a glass of wine and she’ll tell you.’”

Born Brigid Emmett Berlin on Sept. 6, 1939, she was the eldest daughter of Richard E. Berlin, who ran the Hearst publishing empire for more than three decades. Her mother, Muriel Berlin — known as “Honey” — was a well-known New York City socialite.

To her parents’ horror, their daughter rejected all manner of propriety throughout her life. She got kicked out of a succession of schools, then married an openly gay window dresser named John Parker at the age of 19 — a marriage that was, unsurprisingly, short-lived. She took up residence in bohemian hotels and changed her name to Bridget Polk as a nod to her intravenous drug use. (Her telephone stage act from the 1960s was titled: “Bridget Polk Strikes! Her Satanic Majesty in Person.”)

By all accounts, it was with Warhol that she found her scene — and a mutual muse.

More than 3,000 people crowded St.

Berlin liked to audiotape everything: concerts, conversations, the neighbors down the hall engaging in acts of BDSM. And with Warhol she found someone who was equally obsessed with the collection of this type of cultural ephemera.

“They would tape each other and the game would be: Who has the original tape?” recalls Fremont, who says the pair often recorded telephone conversations that would go on for hours. “When she was in Munich, for an exhibition of her work at Heiner Friedrich, she called Andy from Munich. It was the 1970s and a call like that was hugely expensive. But it was long enough for Andy to cook a chicken in the oven.”

Both Berlin and Warhol were also obsessed with Polaroid photography and its new-fangled immediacy.

With her camera, Berlin assiduously chronicled those who circulated within the Factory’s orbit: Dennis Hopper, Candy Darling, Gerard Malanga, Joseph Kosuth, Lou Reed, Diana Vreeland and Gerhard Richter, to name but a few. (Richter, also influenced by her Polaroids, made her the subject of his work.)

She chronicled other bits too.

“I heard stories that when men would walk into the studio, they would have to take their pants down for a Polaroid by Brigid,” says Nourmand. “I’ve seen some: It might be a Polaroid and it says ‘Richard.’”

An image of 2-year-old Yuki sitting on a suitcase at Union Station, waiting for a train to take her to the internment camp, resonated for decades.

One of her favorite subjects was Warhol. Another was herself. “I invented selfies,” she once proclaimed.

But if Warhol tended toward a mugshot style, Berlin’s Polaroids were more subtle and experimental. She chopped up her subjects over multiple images. She experimented with double exposure, placing her face over Warhol’s prints or the faces of the famous, such as Willem de Kooning.

In one image, she superimposed the arch from New York’s Washington Square Park with the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

“I did love to take pictures in two countries in one photograph,” she told a crowd at New York’s Strand Book Store upon the release of her book. “I used to go to Washington Square to the arch, take a picture of that, then get on a plane and go to Paris and take a picture of that.”

“People weren’t really doing double exposures when she was,” says Fremont. “She really worked on those things.”

Berlin was a messy figure: a daughter of Republicans who liked to dwell in New York’s cultural demimonde — then went on in her latter years to brag about how much she loved Fox News. (The rich never lose sight of which side their tax cuts are buttered.)

During her 2015 outing at the Strand, she described watching a filibuster led by Rand Paul as “more like an Andy Warhol movie than anything Andy ever did.”

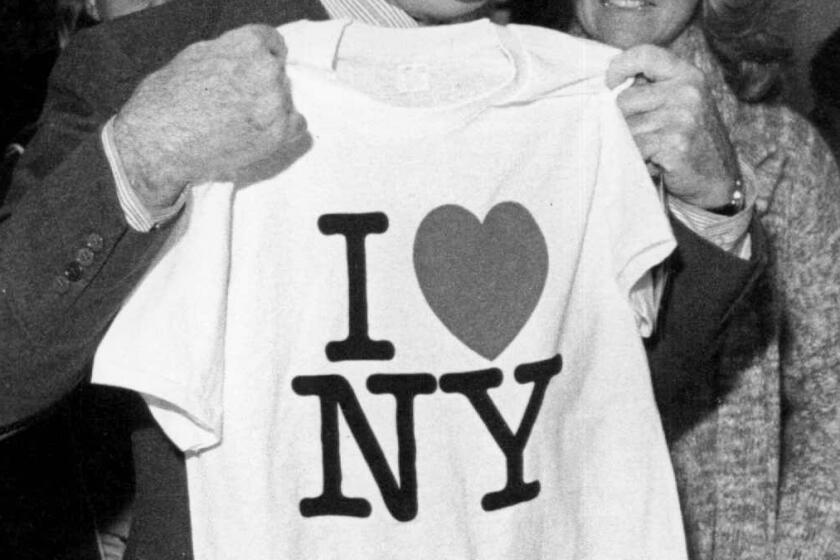

The man behind the ‘I [Heart] New York’ logo and New York magazine’s pop-psychedelic punch in the 1960s shaped how we use symbols.

This messiness is present in her art, which, in this hyper-polished age of Instagram, remains fresh.

“Brigid Berlin didn’t want to own art,” writes filmmaker John Waters in the foreword to her book, “she wanted to be art and she was — on permanent loan to bohemian society.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.