How Ebony and Jet magazines aim for a comeback. New CEO: ‘I want my people back’

The current media landscape is hardly conducive to launching a publication. Ad-funded journalism has sharply declined. Digital subscriber bases for newspapers and magazines have proved hard to increase. And that’s not to mention the COVID-19 pandemic, which has crushed fledgling print and digital outfits.

And yet Michele Ghee, who’s been tapped to relaunch iconic Black magazines Ebony and Jet, said she’s up for the challenge. She is taking over as chief executive after the publications’ purchase out of bankruptcy by former NBA player Ulysses “Junior” Bridgeman and his family.

For the record:

12:57 p.m. Jan. 22, 2021This article says a photo of Emmett Till appeared on the cover of a 1955 issue of Jet magazine. The photo appeared on an inside page.

“This is personal for me,” Ghee said in an exclusive interview days before the sale was to be finalized this week. In describing why she wanted to lead the resurgence of these brands, the Oakland native cited a desire to build a company she would want to go to every day, one that celebrates the fullness of the Black experience and responds to what Black readers want from their media.

But at a time when mass culture and mainstream publications are hyperfocused on amplifying diverse voices — with the prevalence of verticals focused on news of importance to Black people and the creation of teams and positions that focus solely on race — the path ahead for Ebony and Jet is daunting.

The Mellon Foundation grants nearly $1 million to Lula Washington Dance Theatre, part of an effort to correct systemic inequality in arts funding.

Founded in 1945 by Chicago-based publisher John H. Johnson, Ebony magazine was one of the leading publications known for chronicling all facets of Black American life. Along with its sister publication, Jet, which was founded six years later, these periodicals have archives that reflect Black and American history, offering a counterweight to mainstream media’s persistent erasure and marginalization of communities of color.

Take, for example, the now infamous photo of Emmett Till’s mutilated body, taken by a Jet magazine staff photographer. It was the magazine’s Sept. 15, 1955, cover, but white publications refused to print it. Or Moneta Sleet Jr.’s Pulitzer-winning image of Coretta Scott King holding her daughter Bernice in a front-row pew at Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral. Sleet was a longtime staffer at Ebony.

Beyond chronicling the tragedies and traumas that Black people experienced, Ebony and Jet — in the same ways Essence, Vibe and others would later — also documented the community’s joys and triumphs. For many, Ebony and Jet were early sites of possibility, tools that they could use to access potential ways of being beyond readers’ immediate environment and circumstances. It gave an up close and personal look, through visuals and written word, at Black musicians, models, writers and other celebrities who were underplayed or downright ignored by other media.

“It’s impossible to overstate the significance of Johnson publications in telling the story of Black America,” said Donovan X. Ramsey, curator of the Instagram page @blackmagcovers, an ode to iconic magazine covers featuring Black folks. “For many years, Ebony and Jet were the only outlets where Black life was reported on seriously, or covered at all.”

They were a connective tissue of sorts, he said, for a nationally dispersed Black community — so much so that most Black people of a certain age can recall thumbing through the pages at the barbershop or beauty salon. Like pictures of King, Malcolm X and Black Jesus hanging on the walls, Ebony and Jet were commonplace decor in Black homes across the country.

Times have changed, though. As the broader media industry experienced its shifts, Ebony and Jet, and similar outlets deemed “niche,” struggled. Jet ceased print production in June 2014. Two years later, Johnson Publishing sold both publications, save the photo archive, to private equity firm Clear View Group. Under new ownership, woes continued as unpaid freelancers sued Ebony, and the publication ended its print operation in 2019. Although Bridgeman’s $14-million purchase of the titles marks a potential revival of these legacy outfits, they are at once burdened by and resting on their history as they chart a new future.

“Those publications came out of a specific vision and worked for a specific time,” Ramsey said. “It’ll take someone with John Johnson’s business acumen, his understanding of Black communities and his commitment to quality journalism to make Ebony and Jet work again. It’s not an impossible feat but a tough one for sure.”

Ghee, though fiercely excited for the journey ahead, isn’t naive about what she’s walking into. As a sales executive with more than 20 years of experience spearheading teams at BET and CNN, among others, she acknowledged that the landscape has changed from when Johnson founded the publications. Print is largely withering and digital publishing is a game of impressions. She’s also aware that a successful media brand in 2021, especially a Black one, must rise to meet a moment of sociopolitical unrest and accountability. That means she must first lead the healing of wounds that Ebony and Jet created for the small staff struggling to keep its web pages alive and the dozens of writers and other freelancers whose invoices went unpaid.

“I might not be able to make everyone whole,” she said, “but I can make them healthy, and I am committed to that.”

The vision for Ebony and Jet, fashioned in close collaboration with Bridgeman’s daughter, Eden Bridgeman, who has taken the lead representing the family, can be summarized in a few words that all start with the letter B: Black, bold, brilliant and beloved. While some presence in print has not been ruled out, most efforts will be concentrated on the digital audience, with an emphasis on reporting, commentary and video. Experiential events, such as a revival of the Ebony Power 100 gala, are likely to be a major revenue stream.

Ghee said she’s treating the enterprise like a startup, “although it has 75 years of history that I have the honor and privilege to tap into.” Ebony will target Black folks ages 25 to 54, while Jet will target those 18 to 34.

“That’s how I’m going to talk about it in the marketplace,” she said. “I need folks to know that I have a budget, based on the amount paid for this asset, and I have to operate in those confines.” Such an approach also allows her eventual team to not be bogged down by the legacy it’s inheriting as it creates publications that reflect what Black consumers want.

Black audiences no longer have to get their news from local Black newspapers and a few national magazines. From Blavity and TheGrio to the Medium publications Zora and Level — not to mention blogs like the Shade Room and LoveBScott — a host of outlets cover Black communities. They all serve as rebukes of a media ecosystem that largely didn’t make meaningful efforts to elevate Black voices and narratives until the aftermath of the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor killings and the resulting uprisings last summer. To Ghee, there’s a place for them all.

But her mission is clear, with an eye at the mainstream outlets who’ve often placed restrictions on its Black writers and talent in terms of how they can tell Black stories, the mass media whose impressions bank on Black culture for viability without necessarily giving back to Black communities.

“I want my people back,” Ghee said, “and we’re going to do what it takes to get them.”

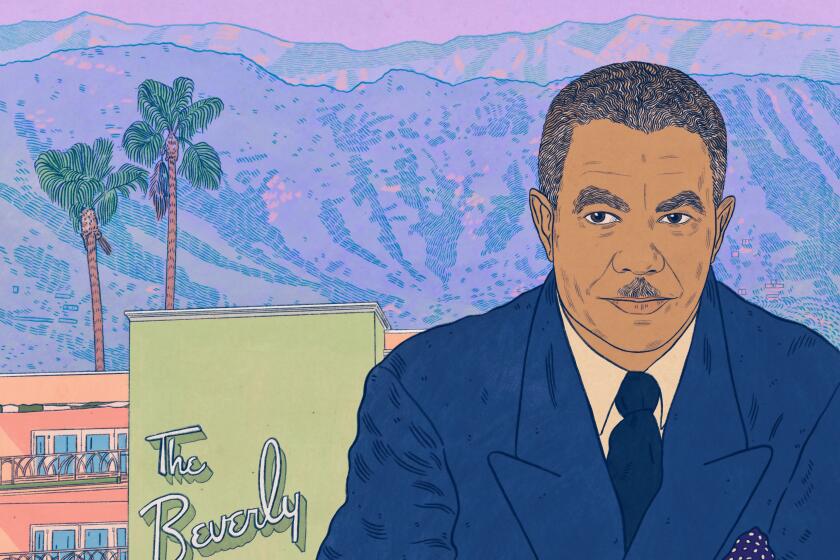

Six buildings that tell the design story of Paul R. Williams, the first Black architect in the AIA. His work is little studied, but his archive, acquired by the Getty and USC, is about to change that.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.