‘Big Short’ screenwriter breaks down Wall Street’s GameStop meltdown

- Share via

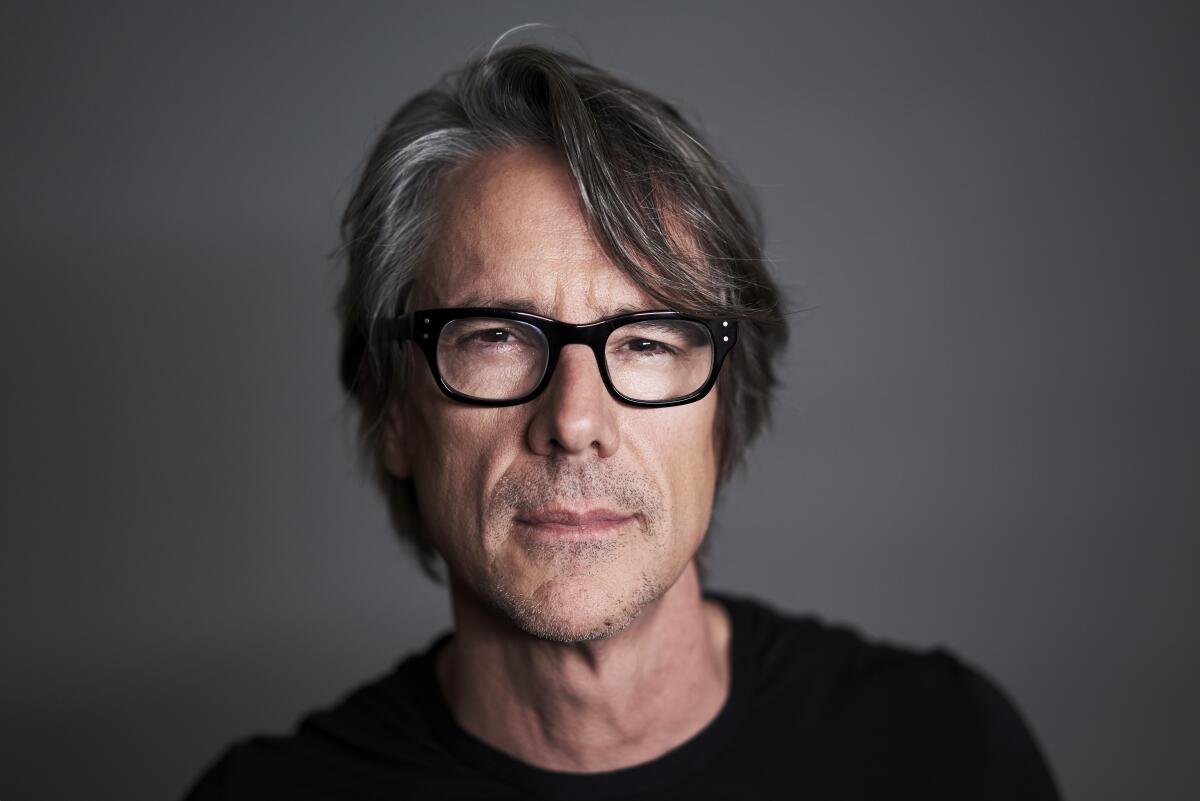

When a bunch of random day traders on Reddit recently sparked a major Wall Street frenzy, it didn’t take long for screenwriter Charles Randolph’s phone to start ringing.

As the Oscar-winning co-writer of Adam McKay’s 2015 financial-crisis dramedy “The Big Short,” Randolph had shown that it was possible to take a dizzyingly complicated Wall Street story and successfully translate it for a mainstream audience. (Randolph and McKay adapted the film from Michael Lewis’ 2010 bestselling book, “The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine.”) Now, with armchair investors snapping up shares in the beleaguered video game retailer GameStop, putting the squeeze on high-flying Wall Street power players who’d bet against the company and sending markets into a tizzy, Hollywood saw the potential to cash in on another wild Wall Street tale.

“There’s already a lot of activity around this,” says Randolph, citing GameStop projects in the works at Netflix, MGM and elsewhere. “I’m going to guess there’s probably six serious, active projects.”

Many have already tried to make sense of the GameStop phenomenon for laypeople, with varying degrees of success, including one L.A. comedian who went viral with a video explaining it as a rift over garden “hedges” between wealthy investors and an “online reading club.”

The Times spoke to Randolph, who most recently wrote the 2019 Fox News sexual-harassment drama “Bombshell,” by phone from his home in upstate New York to get a more expert take.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

It’s safe to say there wouldn’t be as much interest in the GameStop phenomenon in Hollywood if not for the success of “The Big Short.” Does it interest you as a potential subject to pursue, or are you just going to watch this one as a fan?

I’m going to watch this one as a fan. Once you’ve done something once, it’s not really fun to revisit it. I’m a big believer that you can never get back the initial emotional response to a story. Just the indignation or the delight or the fear you feel — you can never experience that quite the same way twice. I would say that this one is in some ways too close to “The Big Short.”

This story is still unfolding, but do you see the makings of a movie in these amateur investors using the power of the internet to stick it to hedge fund billionaires?

Absolutely. I do find the motivations of the Redditors fascinating — part gamble, part lark, part activism. As characters, the core emotional conflict of the more political types is probably pretty close to characters in “The Big Short”: Anger at greed in the system leads them into an insanely successful trade, but they can’t cash out without becoming part of the problem. It’s a fascinating thing: Like, you’re all for sticking it to the man but are you willing to lose $20 million to stick it to the man?

You can almost feel there’s like a cheering section for the Redditors. The culture’s out there saying, “OK, let’s see how far you’ll take this.” As we watch so many institutions and authorities in this country get taken on by social media-driven groups, the depth of that commitment is certainly something that’s fascinating to watch.

I think what’s so interesting about GameStop is that in a way this is the bill being paid for 2008. What that financial crisis did is it robbed finance-driven wealth of its moral justification — it was like, “Oh, the bond market is just a casino.” Historically, finance has protected itself by insularity and complexity and regulation. And all three of those are kind of being blown up now by the internet and entrepreneurs pursuing retail investing. It’s really just about power versus lack of power.

One of the tricky things from a screenwriting perspective would seem to be identifying who exactly the heroes and villains are in this case. And, of course, we don’t know the end of the story yet.

Yeah, it’s also hard in terms of, man, you just don’t want to do a movie about people sitting at a computer. [Laughs] I mean, a bunch of guys sitting around their computers together — that you can get away with. But just one person at a computer in their basement and the wife comes down every two hours and that’s the only dialogue you get to write? You’ll just kill yourself. It’s not good.

In “The Big Short” you found entertaining ways to present arcane financial concepts — most famously in the scene with Margot Robbie in the bubble bath explaining subprime loans. How might you pull off something similar in the GameStop story?

Well, I’m puzzled why a system that wants to capitalize on the spirit of Robin Hood is surprised when the spirit of Robin Hood takes hold.

It’s like short sellers are medieval priests traveling from village to village to sell indulgences, monetizing the sins of others. Margot gets in line, cloaked, ready to buy an indulgence for a robbery. The priest is happy to accommodate her, so she also buys indulgences for a few friends. He takes her cash and absolves them all.

Then, as he leaves town, she’s waiting for him in the forest with a band of thieves.

I feel like this incident will come and go but the underlying dynamic is here to stay, which is people treating investing as a form of expressing their political will. If enough people choose to do that — not just in terms of supporting a company because they do good things but targeting people just because you don’t like how much money they have — that can really fundamentally change the logic of the market.

You’re currently working on another ripped-from-the-headlines film, about the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan. What are you able to say at this point about that project?

Not much. But I’m interested in the story of those first doctors in Wuhan, who are not just fighting a monster but fighting a monster in the dark. They have no idea what this is, and the political limitations around them at the time are fascinating.

What I like to do is just dive deep into a world, and here there’s just this great wealth of material. There was about a month-and-a-half window of phenomenal reporting coming out of China. The society was reeling and they kind of opened all the doors and windows and said, “OK, everyone is just going to speak to what’s happening.” It just felt like an exciting opportunity to tell this great story of what people were dealing with at a time when you had a glimpse into their lives that you were not going to get again.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.