Well-designed rentals L.A. can afford. That’s the mission of the Backyard Homes Project

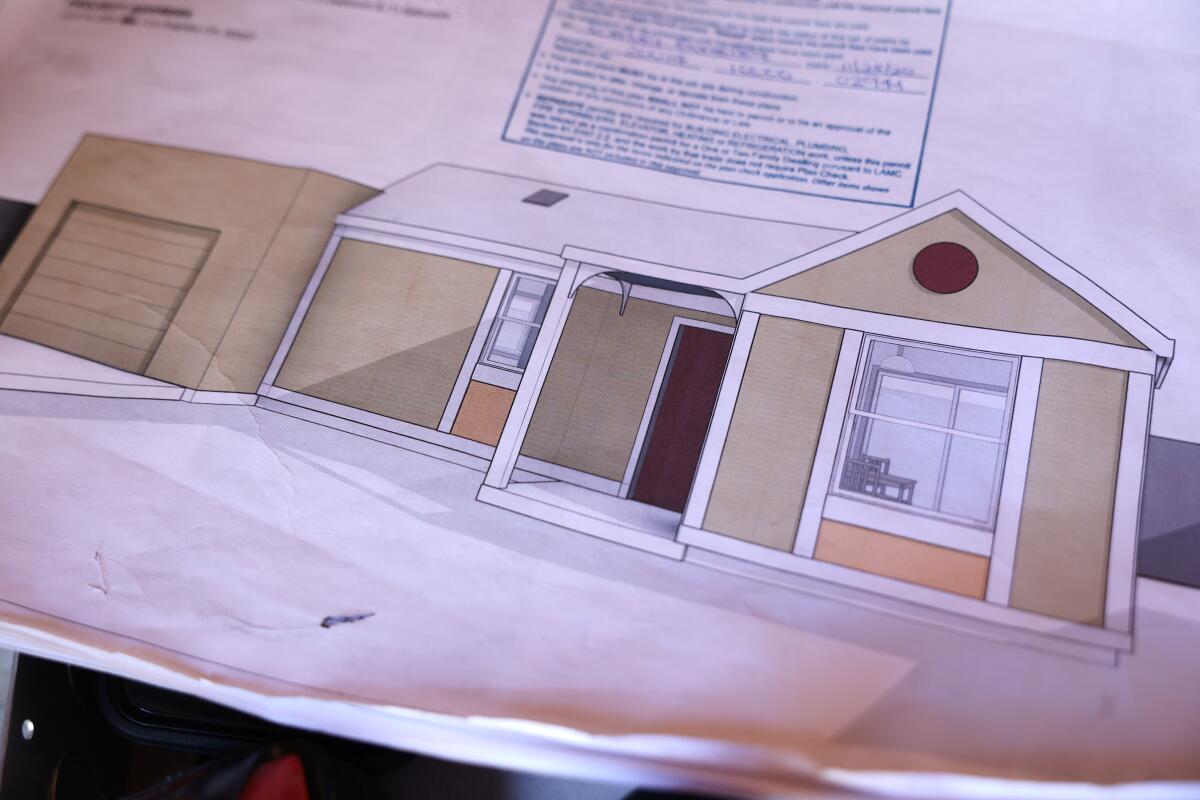

In the University Park neighborhood just north of USC, Katherine Guevara and her husband, David Guevara Rosillo, are building a home that will subtly evoke a California Craftsman, with a pitched roof, porch posts and light ornamentation.

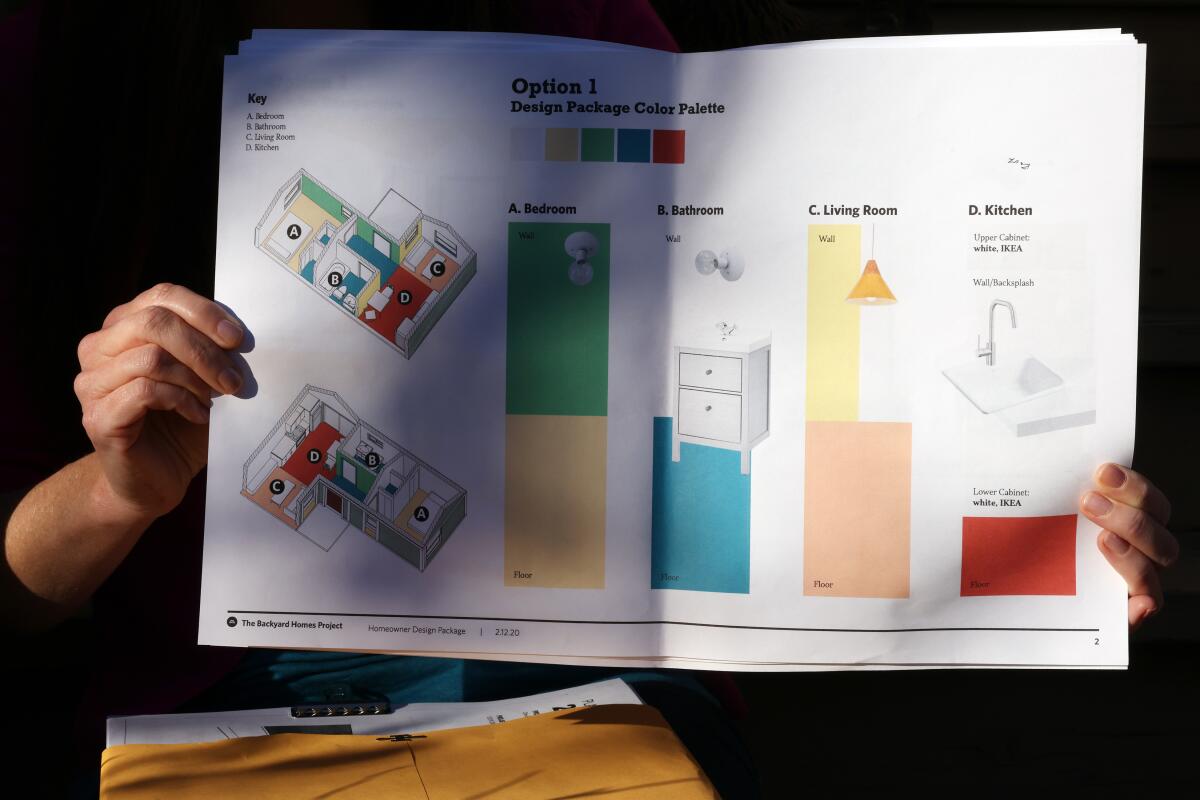

Inside, a burst of colors and patterns reflects the textiles and murals of Guevara Rosillo’s roots in Guayaquil, Ecuador, as well as inspirations such as Frida Kahlo’s La Casa Azul in Mexico City. Green, red, orange, blue and yellow walls and floors will be complemented by a modern Ikea kitchen and bold touches like multichrome Cirque pendant lamps by Louis Poulsen.

For the record:

11:28 a.m. March 5, 2021An earlier version of this article said United Dwelling is offering free ADUs in exchange for a share of the rental income. The company has ended that offer. The article also said Backyard Homes Project’s co-executive director, Helen Leung, grew up in Elysian Heights; she grew up in Elysian Valley.

“We think life should be full of color,” Guevara said. “It will be stunning.”

The home also will carry symbolic significance: It’s the launch of a project addressing L.A.’s affordable housing crisis. The couple are participants in the Backyard Homes Project, which hopes to bring innovation to a field where it’s often hard to come by.

Los Angeles has launched a program with over a dozen preapproved designs from top architects for backyard dwellings, cutting the bureaucracy for needed housing.

Thanks to recent state measures easing regulations on accessory dwelling units — a.k.a. ADUs, or granny flats — Los Angeles has been in the throes of an ADU mania. Thousands of applications have poured in from homeowners across the city, and the ADU has proved to be a lab for housing experiment.

Some companies, like L.A.-based United Dwelling, have offered free ADUs in homeowners’ backyards in exchange for a share of rent. (United Dwelling has since ended that program.) Others are offering modern design or modular construction. An Oakland-based company called Mighty Buildings is even creating 3D-printed ADUs.

The premise of the Backyard Homes Project is to create a one-stop shop: Homeowners like Guevara and her husband promise to rent their ADU to a Section 8 voucher holder for a minimum of five years. In exchange, the homeowners receive affordable design and construction, free project management and favorable financing.

The project is led by LA Más, a nonprofit run by architects, designers and planners who specialize in urban design innovation and aim to blaze a path for more cautious government and industry to follow. The group helped Los Angeles demonstrate the potential for ADUs in 2017 with a pilot project, building a Craftsman-inspired dwelling in Highland Park with a group that included Mayor Eric Garcetti’s Innovation Team and Habitat for Humanity.

For the Backyard Homes Project, they are joined by others, including nonprofit builder Restore Neighborhoods L.A., nonprofit lender Self-Help Credit Union and the community development investment company Genesis L.A. Funding for the project comes from the Wells Fargo Foundations, the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, among others, as well as the nonprofit Los Angeles Local Initiatives Support Corp.

The goal of the program, said LA Más Co-Executive Director Elizabeth Timme, is to confront high housing prices, displacement and lack of economic diversity, not just by making ADU rentals affordable but also by lowering the barriers for low- or moderate-income owners to become landlords, generating long-term income.

“What does economic resilience look like?” Timme asked. “What does it mean to make residents developers?”

Timme and her co-director, Helen Leung, grew up in areas — Los Feliz and Elysian Valley — that have dramatically gentrified since their childhoods, displacing middle- and low-income residents with more affluent homeowners and renters. The duo want to expand the city’s affordable housing options while helping to break through walls of a notoriously insular and specialized field. Leung spent part of her childhood in a public housing project, the William Mead Homes in Chinatown, so she’s intimately familiar with this sphere.

The Backyard Homes Project kicked off in 2019 and has five properties across the city. Each is being built differently, with homeowners choosing from a kit of sizes (studio, one- or two-bedroom) and locally driven styles (including Craftsman, Modern and Spanish). The kit was largely inspired by user-friendly homebuilding catalogs created at the turn of the 20th century, most famously by Sears. (Timme said she spent about $100 buying catalogs on EBay.)

Design and construction of homes start at $100,000 for garage conversions or $130,000 for new construction. LA Más charges a flat fee of $8,000 for design. Through the program, homeowners can qualify to refinance through the Self-Help Federal Credit Union. The credit union estimates the value of the property after the ADU is built, increasing the equity available to borrowers. The new loan adds ADU construction costs to homeowners’ existing mortgage balance. Later, homeowners pay the higher mortgage with the rental income that is subsidized by the Section 8 program. So, for example, the monthly mortgage payment might jump by $800, but the rental income is, say, $1,200.

LA Más interviewed close to 200 potential landlords citywide, eventually winnowing the list to about a dozen, focusing on those who could pay and who fit their goals of serving the lower and middle classes. Timme and Leung said the group has not received any pushback from neighbors. Construction notices are being posted, but until the work actually begins, neighbors might not realize that an ADU is what’s being built or that it will be rented via a Section 8 voucher.

Timme and Leung said a few potential landlords were scared off by the stigma of Section 8 or by the goal of setting rent at a level that’s affordable for a low-income tenant.

“It’s a values alignment type of thing,” says LA Más Program Manager Alexandra Ramirez. “Are you willing to consistently not get what the market value is on this piece of your property? Most people are not.”

Guevara and Guevara Rosillo, who are building their ADU behind the existing Queen Anne cottage where they will continue to live, broke ground Dec. 7 and are scheduled to wrap construction this summer. Guevara said she’s excited by the social goals of the project.

“We think it’s the starting point of a solution,” she said. “It’s the part we could do. It’s everyone’s responsibility.”

The remaining four Backyard Homes are set to begin construction by summer. The good news, Timme and Leung said, is that even though the COVID-19 pandemic and typically painful bureaucratic delays may have slowed the construction schedule, the ADUs are moving forward.

The bad news is that as costs have creeped up, LA Más has been unable to include any low-income homeowners (defined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as anyone making less than 80% median income in Los Angeles) as landlords. For that scenario to work, Timme and Leung said, homeowners would need more local, state or corporate support in the form of funding, tax breaks and longer term or forgivable loans.

“Our hope is that other entities will see this as a model and solve how to fund it,” Leung said.

The program, she added, is really about learning what works and what doesn’t so others can follow. Among the lessons: Many potential landlords want to rent to family members, which Section 8 prohibits. Teaching homeowners why carefully considered design is worth the expense is a constant battle. Interviewing dozens of homeowners can take hundreds of hours because the finances of many ultimately don’t pencil out. You must stick to the kit-of-parts approach rather than allow homeowners to keep customizing. Perhaps the hardest part of the process is familiarizing homeowners with the challenges (and messiness) of construction management.

“We’re not doing this so we can be industry dominators of ADUs,” said Jason Neville, deputy director with the project’s nonprofit builder, RNLA. “We want governments and foundations and companies to know how to do this.”

Adds Mott Smith, adjunct professor of real estate development at USC and a board member with both RNLA and LA Más: “They’re putting in an irrational level of attention to get these projects through. The payoff is a city bureaucracy that now is a little bit better at dealing with these small-scale solutions.”

Governments across California and beyond are working on similar programs to help solve the affordability crisis. Several — including Oakland, Los Angeles County and the Southern California Assn. of Governments — have looked to backyard homes as a potential model.

The city of L.A. recently launched its ADU Accelerator Program, which pairs ADU landlords with older adults in search of affordable housing. Landlords get tenant referrals and tenant case management. Los Angeles County is planning to develop ADUs for the formerly homeless. Other cities launching affordable ADU programs include Pasadena, Oakland, Boston and Washington, D.C., offering varying incentives like project management, zoning relief, tax incentives and public financing.

As Late Modern buildings gain new appreciation, some thanks goes to Wayne Thom, the now-87-year-old L.A.-area photographer celebrated in a new book.

Pasadena’s Second Unit ADU Program, which offers project management and reduced interest loans for new construction and garage conversions in exchange for being a Section 8 landlord, launched in November. Its first homes will break ground early next year. Pasadena Housing Director William Huang said that his city has been developing its program for years and that it’s bumping up against similar challenges. Of the seven new-construction units it is planning, only two have lower- or middle-class landlords. (The Pasadena program for garage conversions focuses on lower-income owners.)

“We’re all learning here,” Huang said. “Someone has to come up with better long-term financing solutions.” That, he said, could come from the state level, just as the state has helped clear the way for the ADU in general by minimizing regulations.

Meanwhile, LA Más, as it has done before, is pivoting to try to better serve the broader challenges of affordable housing and neighborhood redevelopment. It wants to expand its approach to resident-led affordability into new building scales and types, funding models, permitting models (including pre-approved permitting) and even across lot lines. Focusing on its neighborhood, Northeast L.A., it also plans to create a more holistic model that incorporates housing, small business support and community-led design programs.

“People don’t live their lives in a single-issue way,” Leung said. She added that they also want their programs to be more explicitly run by local residents. To leave room for the grass roots. “It’s about the community, not the individual,” she said.

Timme cited a UCLA CityLAB study suggesting that ADUs are feasible for 5% to 10% of the 500,000 single-family lots in Los Angeles, evidence that there’s plenty of room for programs to innovate without bumping up against the limits of supply. A 2019 study by the California Housing Partnership found that Los Angeles has an affordable housing shortage of more than 500,000 units.

“We are nowhere near running out of space for housing in most American cities, including L.A.,” said Vinit Mukhija, professor of urban planning at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs and a board member at LA Más.

Mukhija credits LA Más — along with other designers, housing activists, academics and creative homeowners — with helping to incubate new housing innovation in a city that’s long been known for advances in residential design. He expects that ADU innovations like Backyard Homes will have ripple effects on single-family housing, multifamily housing and beyond.

Library of Congress acquires 269 sketches by late L.A. courtroom artist Mary Chaney. She chronicled trials related to Rodney King, who was beaten by police 30 years ago.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.