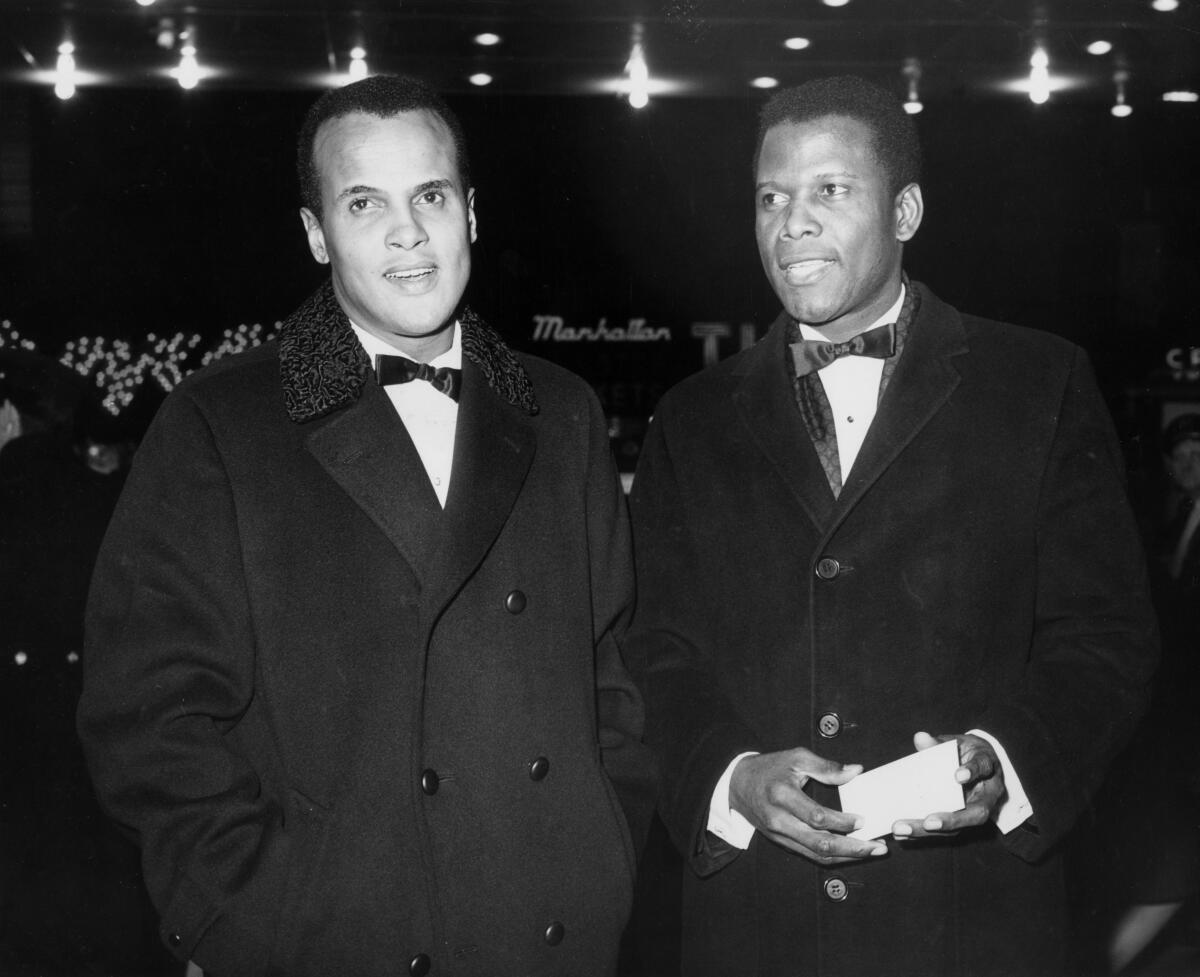

Friends Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte ‘made as much mischief as they could’

It was the 1940s, and Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte were young men working for the American Negro Theatre in Harlem. Poitier was a janitor and drama student. Belafonte was a stagehand. They both studied acting there. They bonded over their mutual desire to do bigger things and their shared West Indian roots. They vowed to work together someday.

This was how a long, enduring friendship was formed, as Belafonte recalled Friday, shortly after Poitier’s death at the age of 94.

“For over 80 years, Sidney and I laughed, cried and made as much mischief as we could,” Belafonte, also 94, said in a statement. “He was truly my brother and partner in trying to make this world a little better. He certainly made mine a whole lot better.”

Indeed, before they ever appeared together onscreen, Poitier and Belafonte collaborated on more important work.

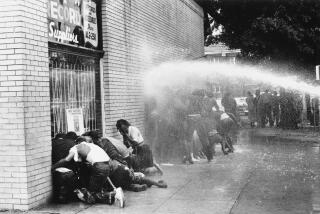

They were both active in the civil rights movement, delivering a bag of cash to Freedom Summer volunteers (and dodging the Ku Klux Klan) in 1964. They were key behind-the-scenes players in the March on Washington in 1963. Even as Belafonte reigned as the King of Calypso, and Poitier became the first mainstream black movie star, they were, as Belafonte put it, “trying to make this world a little better.”

By the time they teamed up on the big screen, for the western “Buck and the Preacher” (1972), they were best friends, though according to some reports they had been feuding. “They became estranged for a few years in the immediate aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, according to Poitier, when they disagreed about plans for King’s funeral, and whether it should also include a protest rally,” says Rick Worland, a film professor at Southern Methodist University and author of the book “Searching for New Frontiers: Hollywood Films in the 1960s.” Poitier advised only having the funeral, according to his 1980 autobiography, “This Life.”

But they reconciled when Belafonte brought the “Buck” script to Poitier, and they agreed to co-star and co-produce. When they determined their choice to direct, Joseph Sargent, wasn’t the right man for the material, Poitier stepped in to direct his first of nine movies.

The chemistry between the two friends is palpable. Poitier plays Buck, a wagon master and Union veteran trying to protect formerly enslaved people and Native Americans in the wake of the Civil War. Belafonte is the wily Preacher, a bit of a con man who nonetheless agrees to help his new friend. (They don’t start off as friends: In their first scene together, Buck steals Preacher’s horse while Preacher bathes naked in a river).

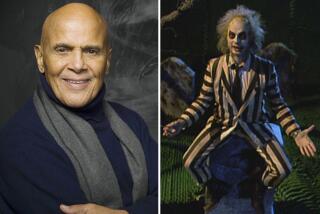

Both “Buck and the Preacher” and the friends’ next collaboration, the 1974 action-comedy “Uptown Saturday Night” (also directed by Poitier), were made during the height of the “blaxploitation” period, marked by cheaply made crime movies that weren’t exactly designed to uplift the race. But with Poitier behind the camera, and starring alongside Belafonte, these movies were different. They were hip, sly, funny and smart, never cheap or tawdry. And they marked a departure from Poitier’s extremely popular ‘60s persona of, as many wags called it, “ebony sainthood.”

Poitier and Belafonte would continue celebrating each other and lifting each other up through the years. Poitier introduced Belafonte at the Kennedy Center Honors awards ceremony in 1989. Belafonte hosted Poitier’s American Film Institute lifetime achievement honors in 1992. Poitier presented the Spingarn Medal to Belafonte at the NAACP Image Awards in 2013. They were always there for each other, each telling the world about the other’s greatness.

Now, only one remains. There will never be another Belafonte. And there will never be another Poitier.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.