L.A. artists offer personal lens on Asian American diaspora in new ‘Off Kilter’ show

- Share via

Housed in a Pasadena building that mimics Chinese architecture, the USC Pacific Asia Museum has historically been steeped in old-fashioned, exotic notions about Asia, Asians and Asian art. Since its early 20th century origins as a curio shop selling Asian and Native American art objects, the museum has focused primarily on the traditional arts of Asia, as if the Asia Pacific region only existed in the past or had only been preserved and documented by Western collectors and photographers. Artist Kim-Trang Tran says she had previously stopped visiting the museum because “it wasn’t relevant to my way of thinking and looking at contemporary art.” However, she has returned in the last few years as the museum has showcased more contemporary art from Asia and the Asian diaspora.

It seems that PAM has tried to foster a closer relationship to Asian communities in the San Gabriel Valley and beyond. Since 2019, seven of its 11 exhibitions have included contemporary Asian American artists or contributors. The latest exhibition in this spirit is “Off Kilter: Power and Pathos,” featuring three local Asian American artists — Tran, Sandra Low and Keiko Fukazawa — who all attempt to make sense of current sociopolitical issues, such as aging, gun violence, racism and economic inequality, by filtering them through a highly personal and idiosyncratic lens. The show is on view through Sept. 4, and curator Rebecca Hall hopes to organize more exhibitions of contemporary Asian American art in the future. “[Artists] give us these keen observations,” she says. “We can find our personal connection to the way they’re processing things, and then they help us understand.”

Low’s often amusing drawings, paintings and prints explore social issues through personal experiences. In the series “Ma Stories,” she records her observations — both funny and poignant — of living with and caring for her mother, who has Alzheimer’s. In drawings and paintings, Low imagines her mother as a gangster from a Jackie Chan film, or a leprechaun running around and hoarding a pile of toilet paper. “If I want to talk about maybe difficult things, it’s going to have to be somehow ridiculous or humorous in some way,” Low says via video conference.

Her “Cheesy Paintings” poke fun at tropes of Western painting — landscape, still life, the artist at her easel — by depicting them dripping in viscous, bright yellow cheese. Punning on the meaning of “cheesy,” Low explores the gap between mainstream ideas of “good taste” and the aesthetic preferences of the Chinese American community in which she lives. “I look around at my relatives and my parents and like, what’s good taste? Tchotchke stuff,” she says.

Accordingly, her paintings are populated with kitschy figurines: a seated cat with a curling tail, a Rococo-style lady carrying a basket and a disembodied hand holding a vase filled with pink roses. She characterized the difference between the aesthetics she grew up with and what’s popular in design magazines as “Versailles versus Eames,” jokingly pitting the excessively ornamented French palace against the iconic modernist designer. Covering tchotchkes and manicured gardens in rivers of greasy American cheese — a substance, she notes, that is foreign to Chinese palates — is her way of embracing the “cheesiness” of the art and decor she loved growing up.

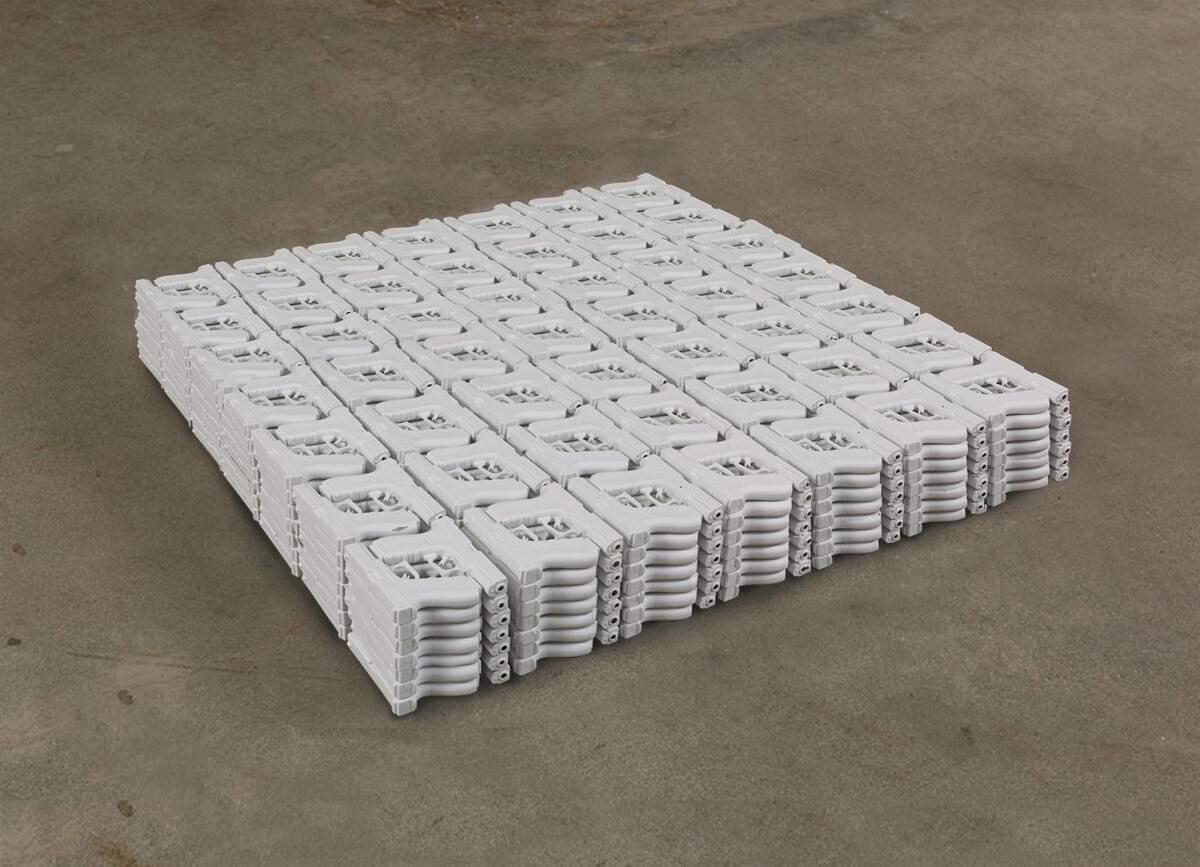

This work contrasts the modernist aesthetics of a squat, square, white block nearby. On closer inspection, it turns out to be made of life-size, porcelain handguns, lying on their sides in stacks of seven on a low plinth. The stacks are arranged to interlock in a grid. Each gun bears the name and age of a person who died from gun violence in the United States and the address where they died. The tomb-like sculpture is Fukazawa’s attempt to come to terms with the seemingly unending gun violence in American society. “So many guns and so many deaths,” she says, “Nobody really talks about the sheer numbers.”

The piece includes 686 guns, a number Fukazawa says represents the number of gun-related deaths in the U.S. between Feb. 21 and March 7, 2022, according to the website Gun Violence Archive. She hopes to one day make enough ceramic guns to represent one year of gun-related deaths in the U.S., but “of course, none of the museums are big enough” to house what the sculpture would realistically look like, she adds.

Tran takes a more historical approach with her video work “Movements: Battles and Solidarity.” The piece is projected across three screens, weaving together three different moments from the early 1970s. On the left is footage from the 1973 “Battle of Versailles” fashion show that pitted American designers against French designers in runway shows at the Palace of Versailles. Tran notes that the event marked the impact of the civil rights movement on fashion, as many of the American models were Black, while the French models were all white. Alongside the projection, the screen itself is embroidered with an image of Black model Billie Blair.

The center screen features images from the contemporaneous war in Vietnam, including footage of a naked, running child with burned skin who repeatedly traverses the screen between scenes of Vietcong soldiers singing and holding rifles. For Tran, who immigrated from Vietnam when she was 9, the imagery of the child was “the antithesis of high fashion.” It was “nakedness, but also beyond nakedness in the sense of the napalm shearing the skin off the children,” she says. This screen features a burned-in outline of the figure of Phan Thi Kim Phúc, who as a young girl, naked and crying after a napalm attack, was famously photographed by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut.

Finally, on the right is footage of American garment workers, mostly women of color, who between 1972 and 1974 staged various wildcat strikes. “I wanted to bring it back home to the States, thinking about who enables the high fashion industry,” says Tran. This screen bears silkscreened images of the protesters and their signs.

With its thought-provoking views into current and historic realities, “Off Kilter” offers ballast for navigating our ever-changing, ever-challenging times.

'Off Kilter: Power and Pathos'

Where: USC Pacific Asia Museum, 46 North Los Robles Ave., Pasadena, CA 91101

When: Wednesdays – Sundays 11-5PM, Closed Mondays and Tuesdays. Through September 4.

Info: info@pam.usc.edu, (626) 787-2680

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.