Review: The ancients live on forever in Cy Twombly’s abstract art, now on view at the Getty

Immortality is what makes a god a god. Launching a thunderbolt is an attention-getter, while the transformation of a human projection into an animal avatar can be disconcerting. Feeding a multitude with just five loaves and two measly fishes — now that’s impressive.

But immortality seals the deal. Globally, assorted gods have patrolled assorted underworlds for millennia, with death as their gloomy guard duty. But, with rare exception, gods themselves don’t die. That makes them different from you and me.

And different from Cy Twombly, the American artist who died in 2011 at 83.

A compact and well-considered new show at the J. Paul Getty Museum does a deep dive into the relationship between his well-known painterly abstractions, which emerged into prominence in the 1960s, and his obsession with the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome. (Surprisingly, the show is on view at the Getty in Brentwood, not at the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades, home to the museum’s ancient art.) “Cy Twombly: Making Past Present” zeroes in on the artist’s poetic visual response to Mediterranean antiquity.

The show does a good job of exploring how Twombly did it, even if it isn’t clear exactly why Mediterranean antiquity should be a pressing matter for contemporary abstract painting. I think immortality goes some distance toward explaining that. Whatever subjects Twombly took on — epic histories of war, say, or classical ideals of beauty — he framed them as painterly interactions where gods dwelled.

War in Twombly’s art is infused with references to Mars, beauty to Venus. Apollo, a god assigned multiple duties, turns up for both battle and beauty.

But contemporary art is made in a culture determinedly secular in its social and artistic life, never mind one where ancient history is, well, ancient history. For us, unlike for ancient civilizations, a great work of art is itself an emblem of potential immortality. After all, what is the purpose of a museum — a thoroughly modern invention — but to function as a mechanism to preserve art objects for an eternity? Twombly’s invocation of the past asserts our present conviction of artistic immortality.

The show was chiefly organized by Christine Kondoleon, curator of ancient Greek and Roman art, and Kate Nesin, curator of contemporary art, both at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where it travels next year. (Getty curators Richard Rand and Scott Allan have overseen the current installation.) They selected 12 paintings, 27 works on paper and 11 sculptures by Twombly, which they interspersed with ancient Greek and Roman objects, most of them once owned by the artist and displayed in his home and studio.

Paintings by Twombly are an acquired taste. Only slowly does what initially appear to be messy, dashed-off scribbles and a few names and words put down in awkward penmanship reveal themselves to be something more.

In fact, an elegance, even a glamour emerges. Twombly brought great sophistication to the late-20th century legacy of abstract painting.

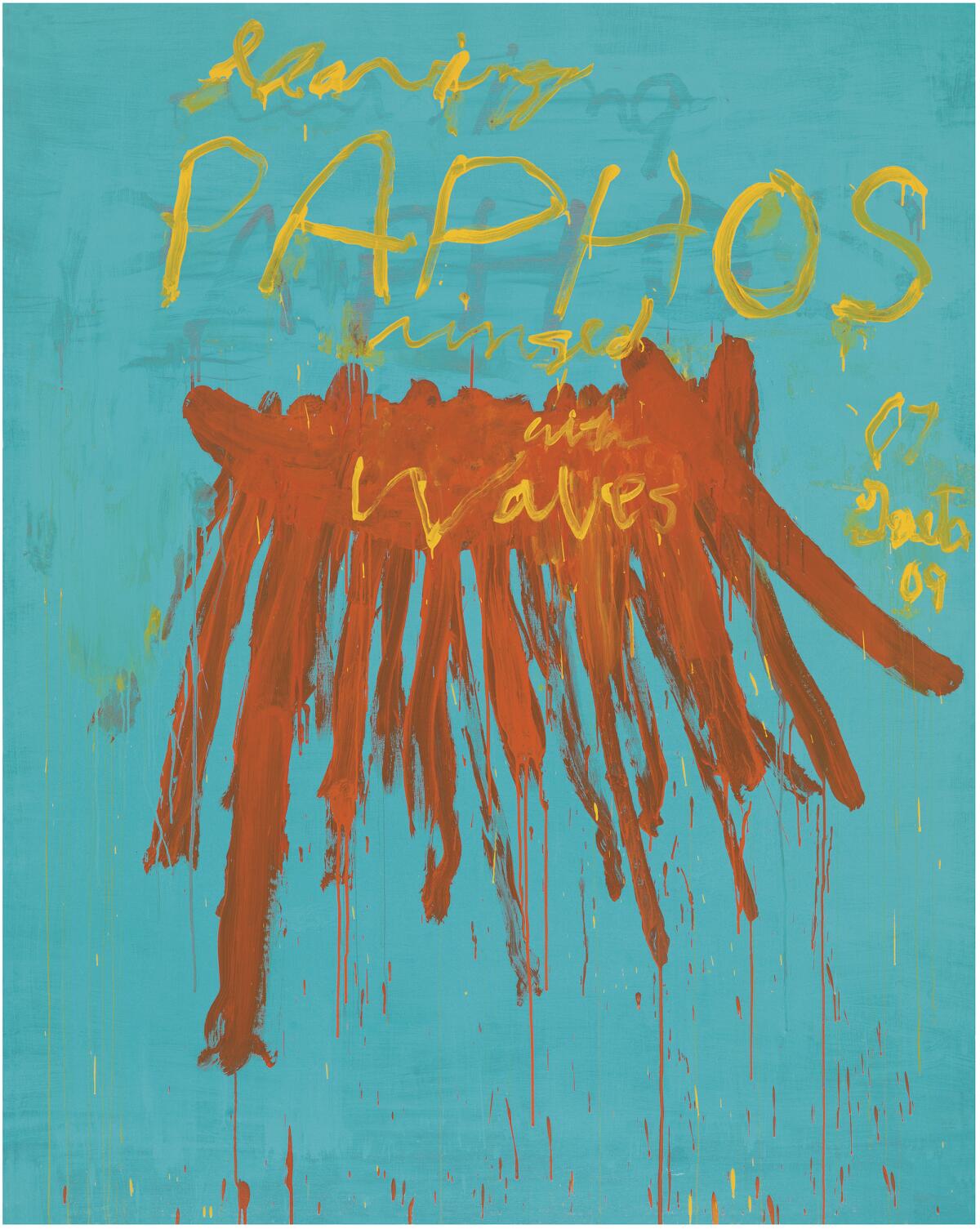

Take “Leaving Paphos Ringed with Waves (IV),” a monumental canvas nearly 9 feet tall and 7 feet wide. A luxurious burst of runny red-orange color marks the center of a voluptuous turquoise field, with the painting’s title scrawled above and over it in pale yellow. The yellow title casts a grayish shadow within the turquoise, a pentimento whose sign of an earlier paint layer signals a stratum of history. The runny burst’s intimation of a boat with oars afloat on a transparent sea is tied to ancient Paphos, the Cypriot city that’s the mythic birthplace of Aphrodite, Greek predecessor of Roman Venus and goddess of sex and beauty.

Say this for Twombly: The guy had style.

Twenty-one art shows, theatrical productions, classical concerts and operatic works our arts critics are looking ahead to in the coming months.

What else he had hasn’t always been easy to determine. Twombly’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles was in 1968 (at the pioneering Nicholas Wilder Gallery), but the work of the longtime American expat to Italy — he moved to Rome in 1958 and stayed in that country for more than half a century — has been seen here only sporadically since then.

The 1994 traveling retrospective from New York’s Museum of Modern Art came to L.A. at the Museum of Contemporary Art, while across the street the Broad museum today features a relatively permanent gallery selected from the roughly two dozen Twombly paintings and sculptures in its collection — one of its largest holdings by a single artist. (A second big “Paphos” painting in the Getty exhibition is on loan from the private collection of Edythe and the late Eli Broad.) Gagosian Gallery showed several of Twombly’s last paintings in a memorial exhibition after the artist’s death. And that’s about it.

Some of the most compelling things in “Making Past Present” are works on paper, a material whose obvious connection to writing emphasizes Twombly’s paintings as visual poems. A monumental 1970 composition at the entry is made from 30 sheets arrayed in a grid, six across and five down, each sheet covered in thin, brushy, light gray oil paint. Wave after wave of gestural scribbles in deep blue crayon repeat, like incomprehensible penmanship. The repetitious “writing” comes across as a frustrated but resolute effort to communicate.

Twombly’s sculptures are among the least compelling things, especially when seen with actual Greek and Roman examples, as they are here. Most are modestly scaled assemblages of wood scraps, unified by slathers of off-white paint. A label dubiously describes an angled wood slat propped atop a box on a pedestal as suggesting “a form emerging from a cresting wave,” like the birth of Aphrodite from the sea; that might indeed be the composition’s source, but the geometric sculpture hardly conveys the organic myth.

The primary exception is a wonderful, lumpy dome in roughhewn cast bronze, which looks like a small mountain. (The lump is about 3 feet high.) Based on a tumulus, an ancient funerary mound, and titled “Thermopylae” after the legendary, blood-soaked battle featuring a small band of Greeks futilely defending their home territory from legions of Persian invaders, the sculpture features four spindly stems arising from the heap, their floral blossoms not yet opened. The stems, bits of life emerging from a place of death, poke at empty space, at once desolate and hopeful. Twombly’s sculpture eloquently captures the conflicted flavor of an immortal story whose vanquished fighters prevail in history’s moral estimation.

'Cy Twombly: Making Past Present'

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: 10 a.m.–5:30 p.m. Tuesday–Friday and Sunday, 10 a.m.-8 p.m. Saturday. Through Oct. 30.

Contact: (310) 440-7300, getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.