Esa-Pekka Salonen’s departure in San Francisco is a wake-up call for arts groups nationwide

When Esa-Pekka Salonen announced recently that he would step down as music director of the San Francisco Symphony next year, he did not say it was to spend more time with his family. He told the truth.

In his statement, which Salonen circulated the same day that the San Francisco Symphony unveiled its 2024-25 season, the orchestra’s music director came right out and said: “I do not share the same goals for the future of the institution as the Board of Governors does.” It was for that vision that a couple of days earlier, Salonen was announced with Nile Rodgers as this year’s recipients of the Polar Music Prize, the annual Swedish award going to the most significant and inventive musicians, in any field, of our day.

Salonen’s vision and invention appeared to be precisely why San Francisco wanted him in the first place. No musician on his level has the potential for tapping into Silicon Valley. When it comes to transformative technology, Salonen has long been a kid in an Apple candy store. Moreover, if any great conductor could wrest millions of pocket-change dollars from arts-adverse tech companies, Salonen seemed the one.

Signing Salonen in 2018 was a considerable coup. At 60, he had become one of the most sought-after conductors and composers. His 17-year tenure as the Los Angeles Philharmonic music director had shown the world the potential wonders available to a 21st century orchestra. But Salonen was just coming off a more discouraging music directorship of the Philharmonia Orchestra in London, where he had given fabulous concerts but didn’t have the resources to realize the kinds of expansive projects he did in L.A.

That was San Francisco’s bait. “My ideas about an orchestra as an institution,” he told the New York Times in 2018, “my ideas about tech and music, my ideas about repertoire and how I would like to position the orchestra within the community — it just resonated.”

San Francisco clearly promised Salonen his wish list. That included creating a “think tank” of younger artists from many walks of musical and tech life: AI entrepreneur and roboticist Carol Reiley, composer Nico Muhly, avant-garde flutist Claire Chase, jazz bassist Esperanza Spalding, film composer Nicholas Britell, soprano Julia Bullock, composer and pop guitarist Bryce Dessner and uncategorizable Finnish violinist Pekka Kuusisto.

COVID-19 hit. There was no first Salonen season in San Francisco for 2020-21 other than the imaginative online experiment of Muhly’s “Throughline.” The orchestra shut down and, like all orchestras, lost plenty of money. Plus, the pandemic wounded San Francisco more than it did many other major cities, with the exodus of wealthy tech workers to whatever rural remote-work paradise appealed.

Even so, Salonen remained one of the most resourceful conductors during the lost season, and he bounced back in San Francisco with his vision intact and growing. He began major annual June operatic stagings with Peter Sellars and arresting programming in the orchestra’s experimental SoundBox, the hip black-box venue attached to Davies Symphony Hall, which proved a hit with young concertgoers.

There have been problems, some possibly overstated. Davies is not a great hall acoustically, but on my recent visit, Salonen conducted the most sonically astounding performance of Bartók’s “Bluebeard’s Castle” I have ever heard. I was warned that the nearby Civic Center BART station has become unsafe. I did not find it disagreeable. Indeed, the orchestra has reported an increase in attendance to Salonen’s concerts from pre-pandemic levels. The endowment has grown as well. At $315 million, it is among the highest for any U.S. orchestra. (The much larger L.A. Phil reported a $350-million endowment a year ago.)

No matter, the board and management are crying the blues. Claiming financial projections don’t look good, the board has embarked on a series of cutbacks affecting the SoundBox, eliminating the creative partners, calling off international touring, reducing commissions and so on. The board now presents the San Francisco Symphony as a survivor forgoing experimental treatment and in need of a cautious caretaker.

Boards! We can’t live with them, and we certainly can’t live without them. By their very nature, they are about money. They keep the institution running. They raise funds. When boards are excellent, they recognize the artistic vision and make miracles happen. But that can take some doing, because by their very nature, they operate by committee.

What has changed over the years is that many boards have become increasingly corporate, increasingly powerful and increasingly clueless. Salonen, no doubt, thinks like an Angeleno. He was L.A. Phil music director in 1999, when Deborah Borda was hired to be its chief executive. The orchestra was millions of dollars in the red, and Borda had the reputation for being fiscally tough.

What the success of John Cage’s ‘Europeras 3 & 4’ in Detroit and Christian Wolff’s 90th-birthday celebration in New York reveal about this moment in music.

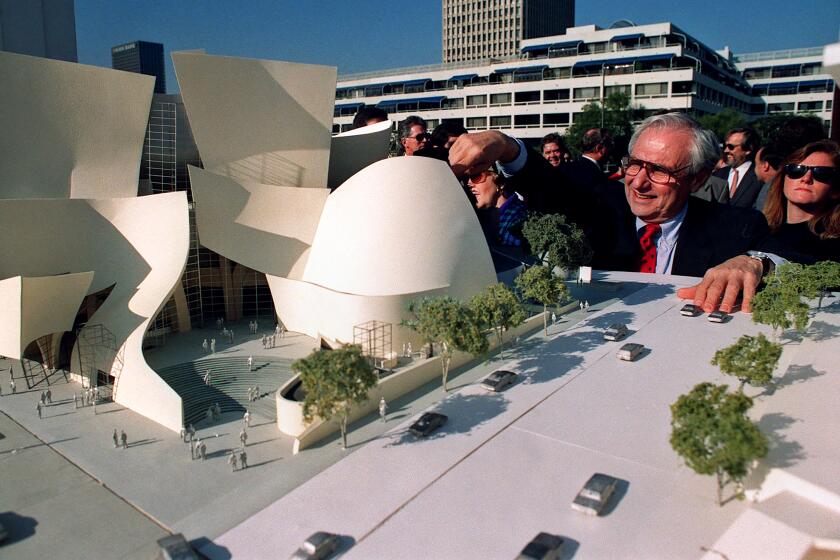

Although this has become legend in the orchestra leadership world, it obviously bears repeating. Borda welcomed Salonen’s big ideas. She realized the tremendous promise of Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall, then under construction. She cut costs where it didn’t matter, such as selling off the previous executive’s pretentious antiques and furnishing her office from Ikea. Otherwise, she spent like there was a real tomorrow, convincing the board that the orchestra and institution had to have the resources to demonstrate to the public what it could do if it were to thrive. The rest is history.

Times, though, are changing. The imperious and visionary L.A. Phil manager Ernest Fleischmann — who hired Salonen against the wisdom of some on the board who were dubious of an untried young conductor who specialized in contemporary music — did what he wanted, the board be damned. He also refused to give in to pressure from the Music Center board, the county Board of Supervisors, this newspaper, L.A. Phil subscribers and the public when Disney Hall fundraising faltered and the whole thing seemed like some kind of pointless avant-garde Pollyanna project from a vain architect. The rest — here we go again — is history.

The important question is whether that kind of resistance is possible against today’s powerful modern boards. Reportedly the San Francisco board is contemplating a renovation of Davies to the tune of as much as $250 million. Salonen’s far more radical and far less expensive goal had been to put into practice Gehry’s proposal to transform two old warehouses on Treasure Island into indoor and outdoor concert halls, with acoustics by Yasuhisa Toyota. That could have led to Treasure Island becoming an arts island, to say nothing of the treasure that the board then would be able to raise from Silicon Valley trendsetters.

Salonen’s calling out the cluelessness of the San Francisco Symphony is a wake-up call to the future of not just orchestras but all American arts institutions, including his old orchestra here in L.A. Boards tend to be composed of highly successful individuals who are not always in the habit of listening to others, especially others who want to risk their money.

Much of the L.A. Phil’s success can, indeed, be credited to far-sighted, even utopian, artistic and administrative leaders. But in an odd and worryingly unprecedented turn of events, the L.A. Phil board is searching for both a chief executive and a music director, with little transparency about the process.

Esa-Pekka Salonen and the San Francisco Symphony add color and, courtesy of a perfumer at Cartier, scent to Scriabin’s ‘Prometheus.’ Does the novelty prove effective?

We might want to remember that every music director at the L.A. Phil has been selected not by committees and not by boards but by autocratic executive directors who have a kind of insight that the board (or even the orchestra itself) doesn’t have. Fleischmann brought us Salonen. Borda chased down Gustavo Dudamel. Dorothy Chandler took a big chance on Zubin Mehta. William Andrews Clark in the 1930s snagged Otto Klemperer. Not a single one might have passed the muster of a committee.

The L.A. Phil board is sure to be interviewing prospective chief executives without wanting to know who they would want as music director. That’s assuming, of course, the board doesn’t decide to find its own music director. At least we have history on our side.

In yet another curious turn of events, Salonen is scheduled to bring his orchestra to Disney Hall on Friday night to perform John Adams’ magnificent symphony “Naïve and Sentimental Music.” It was commissioned by the L.A. Phil, and Salonen conducted the 1999 premiere, back in the acoustically challenged Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. I hope members of San Francisco’s board come down to L.A. to hear what its orchestra sounds like in a Toyota hall and to see just how valuable touring can be. When L.A. Phil board members heard Salonen conduct Stravinsky on tour in Paris in 1996, they suddenly came on board to build Disney.

Unless the San Francisco Symphony somehow convinces Salonen to stay, for which the musicians are lobbying, the board has one good option and one option only. Find another conductor with big ideas, most likely someone young and exciting. Make the same promises it made to Salonen. And keep them.

After 20 years, Walt Disney Concert Hall has changed Los Angeles and its philharmonic orchestra, but we now have to live up to Frank Gehry’s full, original vision.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.