Opera gets slapped with the ‘elitist’ label. L.A. proves just how wrong that is

The label of elitism sticks to opera like superglue. The label is a fake, but one for which no cultural chemical capable of removing it has yet proved effective. Still, opera populists are trying and appear to be making progress.

Los Angeles Opera last week unveiled two new productions of operas old or avant-garde: Verdi’s 19th century chestnut “La Traviata,” and Huang Ruo’s 2021 “Book of Mountains and Seas,” based on ancient Chinese myths. Both are literally worlds apart, they were given in theaters large (the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion downtown) and small (the Broad Stage in Santa Monica), and they were designed for different audiences. The performances I saw were well attended and enthusiastically received.

Both raised the question of what makes opera elite, as opposed to, say, a Lakers game. Wealth or privilege, say the lexographers at Oxford, a university where wealth and privilege have sway. As I write, tickets purchased on the L.A. Opera website for the Wednesday performance of “La Traviata” range from $89 to $329. The next night, the Lakers take on the Denver Nuggets at Crypto.com Arena. Cash in your crypto (if you still can) for nuggets of gold: Tickets on the Lakers website begin at $249, rising to five grand. Event parking at the Music Center is $10, a quarter of the price Crypto.com charges for a Lakers game.

Opera has been popular entertainment through much of its early history. Castrati were the pop stars of the Baroque era. At the time Verdi wrote “La Traviata,” he was so popular that his latest tunes were as closely guarded before a premiere as a Beyoncé track.

There were peanut galleries in all the great 19th century European opera houses, and there have been cheap seats ever since. As a student, I often attended San Francisco Opera several times a week, standing room being no more than the price of a movie. Tickets for L.A. Opera mainstage productions start around $35 or less, and they go fast.

The intimidation factor is often the main reason credited with keeping new audiences away from opera. What to wear? There is no dress code. Some people dress up, and hard-core fans can be found in jeans.

Klaus Makela, appointed music director of the Chicago Symphony at the age of 28, has been likened to Gustavo Dudamel. Why orchestras’ chasing of youth could have downsides.

What to know? When I listen to a rap recording, I sometimes employ a guide to follow allusions in the lyrics that may escape me. If “La Traviata” is a mystery to you, arrive an hour early and the company’s music director, James Conlon, will explain it to you in his engaging pre-performance talk. A plot synopsis is in the program and English translations of the libretto are projected on screens during the performance.

That said, there is always the danger of a welcome turning into glad-handing. In the recent past, L.A. had been in the process of becoming a leader in taking bold theatrical chances, making our opera some of the most relevant theater anywhere and L.A. the hippest opera city in America. But we have entered a culturally risk-adverse period. Our present age of anxiety — which includes post-pandemic economic challenges to the arts, diminished attention spans and audiences seeking escape from all but virtual reality — has ushered in an atmosphere of caution in just about everything presented to the public.

A successful L.A. Opera strategy for building new audiences has, therefore, been precisely the opposite of challenge. Real old-fashioned opera, the more retro the better, has become the new cool.

The “Traviata” production the company imported from San Francisco Opera fits right in with period sets and costumes so formulaic as to feel ironically surreal, along with park-and-bark direction for the singers. There is a hint of wink-wink-nod-nod kink in a party scene (this is from San Francisco, after all), comic not erotic.

The performance sounds far better than it looks thanks in large part to Conlon’s commanding conducting that makes everything seem to matter despite appearances. The standout in the cast is the Violetta of Rachel Willis-Sorensen, her silvery and supple soprano making for a more brilliant than affectingly consumptive character. The starchy tenor, Liparit Avetisyan, as Violetta’s lover Alfredo, seems to like singing to the audience more than to her.

Ironically, the appeal may be that this is just outdated enough and nonthreatening enough to feel newly fashionable. The silly kink brings a smile. Any intimations of feminism dare seem threatening. By escaping modern theater, by not allowing “La Traviata” to be upsetting, we are offered a three-hour escape from reality.

In its attempts at opera for all, the Los Angeles company also has found ways to take opera out of the opera house. On May 3 and 4, Conlon brings back his warm, magnificent, family-friendly and free L.A. Opera production of Benjamin Britten’s “Noah’s Flood” at Our Lady of the Angels downtown. Expect to leave the cathedral feeling better than when you entered.

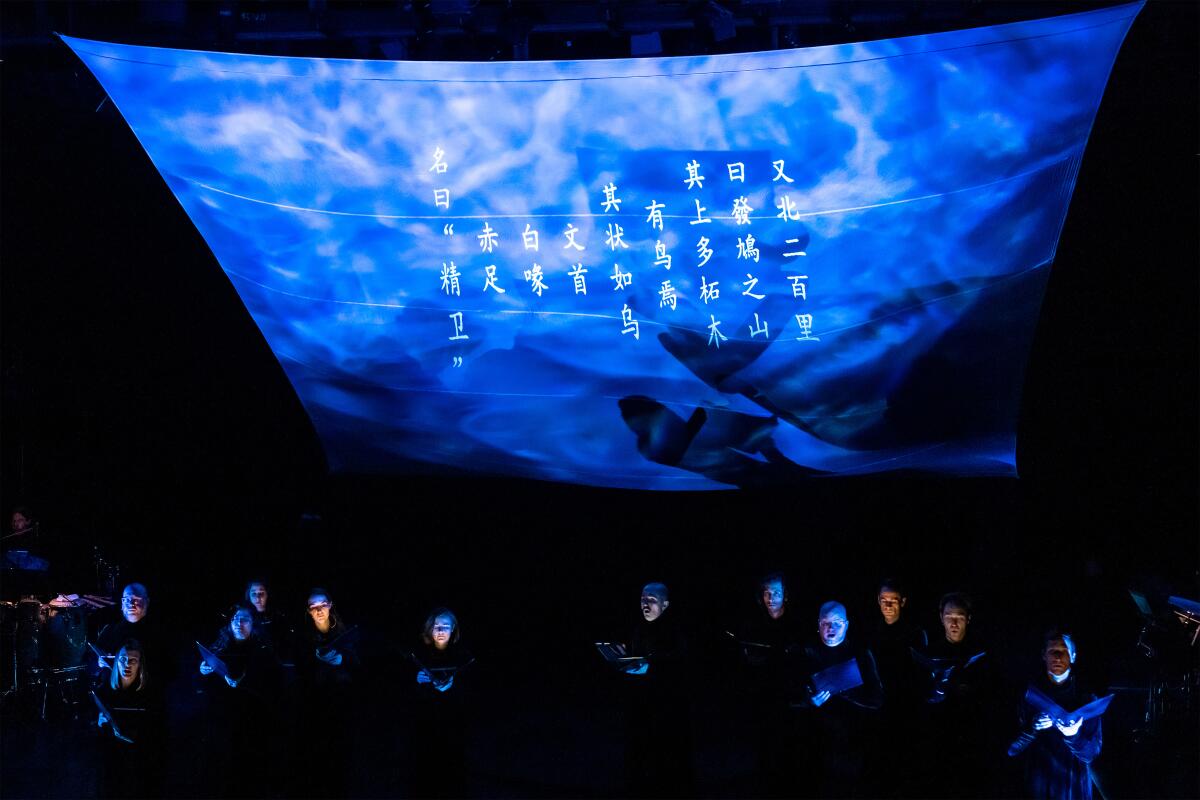

Experimental opera was also sent off Grand avenue. At the Broad Stage, “Book of Mountains and Seas” — part of L.A. Opera’s annual collaboration with Beth Morrison Projects, makers of new opera — was everything that “Traviata” was not. The imaginative production by puppeteer Basil Twist proved stunning. The cast contained a dozen equally ideal singers. What vague narrative there is comes across as barely explicable. Words and music didn’t matter all that much. The escape from reality, in this case, was of the go-with-the-flow variety.

Huang Ruo’s impetus is “The Classic of Mountains and Seas” from ancient China, which describes the mythic plants and creatures with odd powers. The four tales selected from “The Classic” for the opera — the birth of the hairy giant Pangu, a spirit bird who attacks water, the folly of 10 suns, and a giant who thinks he can capture the sun — are dramatized through the fuzzy ritual of a puppet being assembled.

The singers, the Ars Nova Copenhagen, are the real stars. Indeed for the West Coast appearances of “Mountains and Seas,” which is currently touring, this amazing Danish chamber choir might well have set the scene for the 75-minute opera with Lou Harrison’s “Mass for Saint Cecilia’s Day.” The group’s meditative yet exhilarating recording of this Californian mix of Harrison’s gothic chant and ancient Asian tunings is a model for what Huang Ruo was after. Still the sounds were entrancing and the giant puppet impressive.

Love him or hate him, Philip Glass is inescapable. His 20 piano etudes have become essential listening, his impact on three generations of artists indelible.

Atmosphere may not an opera make, but as escapes from reality go, there are far fewer appealing ones than this. And with luck L.A. Opera’s efforts at taking the elitism out of opera may make a difference. In the next two months, the town will be the site of an informal opera-for-all festival.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic is remounting “Fidelio” with Deaf West Theatre next month, Opera America and World Opera Forum host conferences in L.A. in June, and new work is coming from Long Beach Opera and the Industry — along with dozens of offerings from L.A. Opera, the happily populist Pacific Opera Project, Beth Morrison and others. Anyone with a stage, a costume, a voice and an idea is welcome. That is the L.A. opera ideal.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.