Commentary: LACMA finally is getting its satellite space. Regrettably, it’s in another state

For well over a decade, leadership at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has been talking about establishing satellite museum galleries far from the mother ship on Wilshire Boulevard.

In recognition of the simple geographic realities of the region’s distinctive horizontal expanse, the practical logic is: If people can’t easily get to the art, installed at a complex standing midway between Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration downtown and the Santa Monica Pier at the beach, get the art out to the people. It might sound like a solution, but it’s actually controversial, since small satellites dilute the powerful experience of a global art museum to questionable effect.

For whatever reason, however, none have ever materialized for LACMA. Satellite plans have been floated for sites in South L.A., Culver City, South Gate and elsewhere, both as new construction projects and adaptive reuse of existing buildings. Maybe someday, but not yet.

And, no, a room with some art at Charles White Elementary School open to the public for a few hours on Saturday afternoons doesn’t count. That’s a nice educational opportunity for the kids.

In the interim, LACMA touts perfectly routine art loans from its permanent collection to existing area museums, large and small, as an innovative, forward-thinking satellite program, but that’s just marketing promotion. Art museums have done that sort of thing just about forever.

So, it was with some surprise that news arrived in late December that an actual LACMA satellite finally does appear to be on the drawing board — one with a good chance of actually becoming a reality. The surprise: Who could have guessed that the satellite would not be in Southern California?

Indeed, who could have imagined it would be in another state?

LACMA’s first satellite is being planned for Las Vegas, just blocks from downtown’s Glitter Gulch. L.A. County’s famous horizontal spread has oozed all the way across the Mojave Desert and into Clark County, Nevada, 250 miles away. It’s less like NASA landing a human being on the moon than like Elon Musk building a metropolis on Mars.

LACMA might be a de facto museum of contemporary art, but frankly it’s not a very good one.

As bad art museum ideas go, this one is right up there. But it fits LACMA’s similarly bad — and unprecedented — decision to build a new, hugely expensive permanent collection building on Wilshire Boulevard that features less gallery space than it had in the 1960s edifice it bulldozed to make way. (The new building might be ready to open in 2026.) To cement the change, LACMA Director Michael Govan reportedly gave architect Peter Zumthor instructions to design a new building that could never be enlarged. The architect obliged.

It’s the LACMA two-step: Build permanent collection galleries smaller than the ones that were torn down, then fret about having too much art in storage, turning controversial satellites into an imperative. It’s a museum twist on the old joke of the guy who murders his parents, then begs for sympathy because he’s an orphan.

The cockamamie plan in Mid-Wilshire is to install most of the museum’s paintings, sculptures, photographs and other art as clusters of more than two dozen regularly changing theme shows, rather than as a simple permanent collection neutrally organized by chronology and geography. An encyclopedic museum that brings together in one location art objects from every time and place, which had directed LACMA’s professional activities for half a century, was tossed overboard.

LACMA has been test-driving samples of the collection theme-show idea for a couple years now, as the new building goes up. They’ve been pretty vacuous, like the recent forays into “how have artists around the world used different kinds of stone?” and “what is a 17th-century Dutch collector’s cabinet?” (Think of these as Wikipedia shows, piloted by common knowledge.) When the new building eventually opens, another will be under construction in Las Vegas — a three-story, 90,000-square-foot, $150-million building with a $50-million endowment, ambitiously scheduled to open in 2028. It can be a Nevada touring partner for those L.A. thematic entertainments.

Why? Because, despite the misleading name, the Las Vegas Museum of Art won’t really be a museum. It won’t have a collection of its own. Instead, the plan is to borrow all the art it shows from LACMA’s collection, with three exhibition spaces in steady rotation.

In other words, Vegas is constructing a kunsthalle. That great German term describes a collection-free facility that only mounts temporary art exhibitions. LACMA will provide the art loans, apparently for fees that only will cover costs.

What art will LACMA lend to the Las Vegas kunsthalle? There are only two answers — three, if it’s a combination of the other two, which is most likely. All are dour.

One, Vegas gets lent top-tier works of art — the kind any serious institution labors to assemble over decades and takes care to have on view whenever possible for the benefit of local patrons. That means we in Los Angeles won’t have access to chunks of the best in our county museum’s permanent collection — say, Miguel Cabrera’s extraordinary class depiction of a mixed-race family in 1763 Mexico; the dynamic marble bust “Portrait of a Gentleman” by sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the one-time child prodigy who practically invented Italian Baroque art; or maybe Maruyama Ōkyo’s “Cranes,” arguably the finest pair of Japanese screens of the last 400 years to be found in the United States.

Or, the other possibility, Vegas gets mostly second-tier or lesser art — the contextual material, ranging from perfectly fine to mediocre in quality, that museums also rightly collect in order to contextualize and elaborate the history and meaning of the most profound things. That means Las Vegas gets shortchanged.

In short, this satellite plan is a lose-lose proposition. Either Angelenos will be deprived, or Las Vegans will be.

Museum loans are typically made in expectation of future reciprocation, but obviously not this one. The collection-sharing scheme takes advantage of the public’s familiar but false assumption, which goes back to that storage issue. Art museums are imagined having storerooms just bulging with great things that ought to be out on view but never are. In reality, the lion’s share of what’s in museum storage should be in museum storage.

Most of the time, at least. Storage isn’t merely a costly (or sneaky) means for hiding loot away from art-hungry audiences. A huge component of LACMA’s collection, as at many other museums, is light-sensitive material. Thousands upon thousands of drawings, prints, photographs, Japanese paintings on silk, Chinese albums, manuscripts, Buddhist thangkas, book plates, textiles and much more cannot be on permanent view. (Appointment-only study rooms are needed for that.) Protecting cultural objects, not ruining them for public amusement, is a primary museum job.

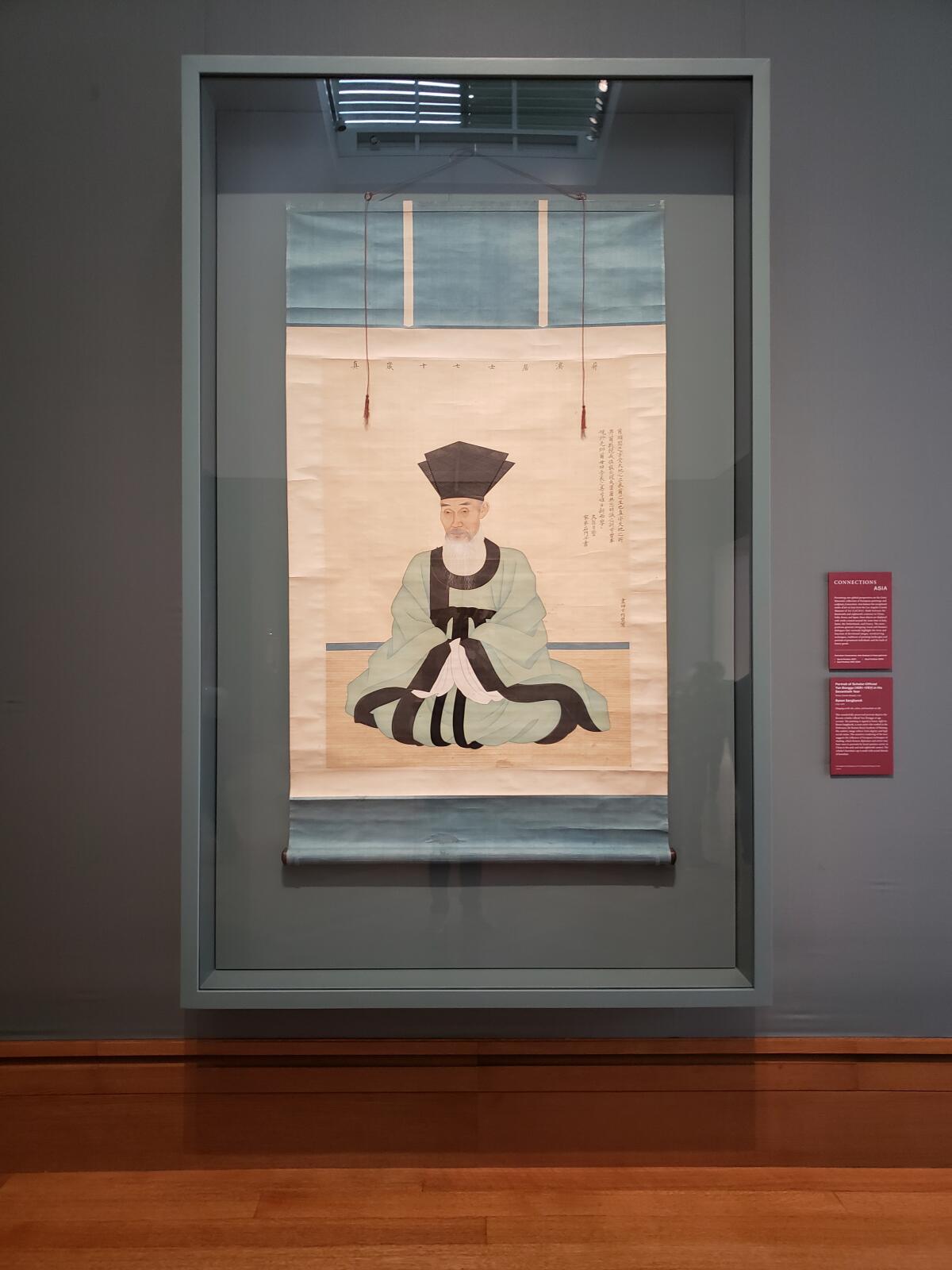

Whether the museum’s gallery is located in Los Angeles or Las Vegas doesn’t matter. Just because LACMA’s lovely 1750 “Portrait of Scholar-Official Yun Bonggu (1681-1767) in his Seventieth Year” by Korean painter Byeon Sang-byeok isn’t hanging here, for example, doesn’t mean it would be fine to hang it there. On a three-month loan last year to the Getty Museum, the scroll, exquisitely painted in ink and colors on silk, looked remarkably fresh for being 250 years old — but that’s because it regularly rests in storage.

LACMA, together with four partner institutions in the area, has been running a worthwhile collection loan program called Local Access for nearly three years. Modern and contemporary photographs and graphics have been the focus. One show, “Before You Now: Capturing the Self in Portraiture” is currently at the Riverside Art Museum. Other program participants include the gallery at Cal State Northridge, the Lancaster Museum of Art and History and East L.A. College’s Vincent Price Art Museum.

The Broad museum in downtown L.A. has been a huge hit. Will a bigger building be worth the $100-million budget?

Riverside is the only one not in L.A. County, but all four are within a 90-minute drive from LACMA. Las Vegas? That’s five hours away. Local satellites might be problematic, but remote ones are just daft.

Expect LACMA to of course deny that the Vegas kunsthalle is its satellite, even though it will essentially be programming the place. LACMA’s Govan and board of trustees’ co-chair Elaine P. Wynn, a billionaire Las Vegas casino magnate and contemporary art collector whose foundation is helping to bankroll the scheme, will both sit on both boards. Fundraising, loans, programming — if the two institutions were truly independent, those interlocking boards would be ripe for conflicts of interest. Which institution gets priority in decision-making, in good times as well as bad?

Recently I spoke with Heather Harmon, the Las Vegas project’s savvy executive director (she’s also manager of “City,” the remote Nevada desert sculpture by Michael Heizer, whose foundation Govan helms). Harmon, whom I’ve known for many years, has been trying to get an art museum off the ground for quite a while, so she was understandably jazzed by the LACMA development.

And why not? LACMA’s satellite arrangement gives Las Vegas a lot, even if L.A. effectively gets nothing from the deal. As we know, the house always wins. It’s a Vegas thing.

Inside LACMA’s plans to share its collection with a new Las Vegas museum: ‘I’m a West Coast booster’

Early this year the Los Angeles County Museum of Art announced a partnership with the planned Las Vegas Museum of Art. LACMA’s Michael Govan and LVMA director Heather Harmon discuss the details of the arrangement.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.