After 32 ‘egregious and cruel’ seasons, ‘Cops’ was canceled. This podcast explains why

Dan Taberski grew up watching “Cops” — not necessarily loving it, mind you, but watching it. Before he started researching the podcast “Running From Cops,” he estimates he had seen about 500 episodes.

The reality series, canceled this week after 32 seasons and more than 1,100 episodes, debuted in 1989 and has aired in syndication since the early 1990s. Much like “Law & Order,” it is so ubiquitous as to be background noise — something consumed passively while folding laundry or making dinner.

“It was on all the time. Sometimes it’s on maybe 15 to 20 times in a single day, just over and over. When something is on that often I think it becomes something different,” said Taberski this week, as protests over the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis have led to questions about pop culture’s portrayal of law enforcement.

To Taberski, the fact that “Cops” — a show that was once considered shockingly graphic — had morphed into something as mundane as wallpaper made it worthy of a critical deep dive.

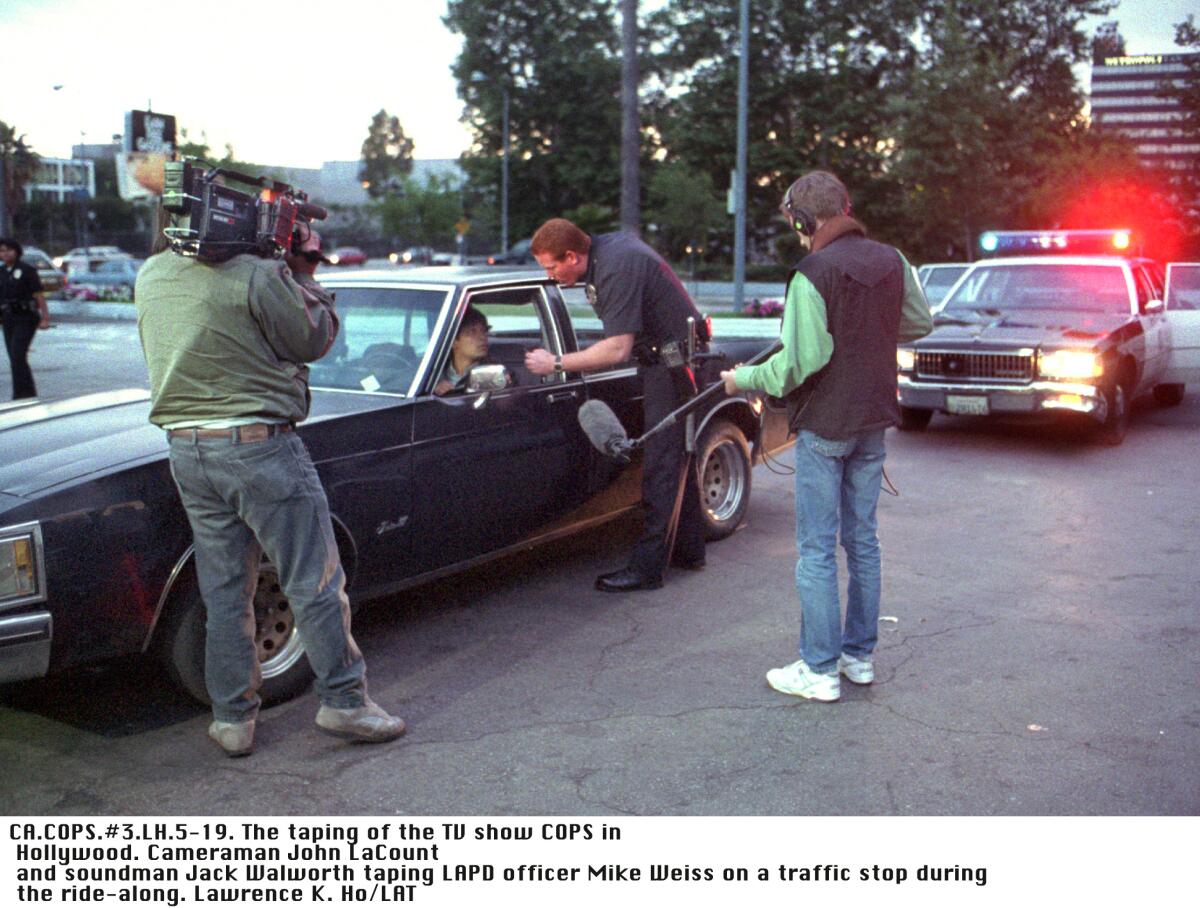

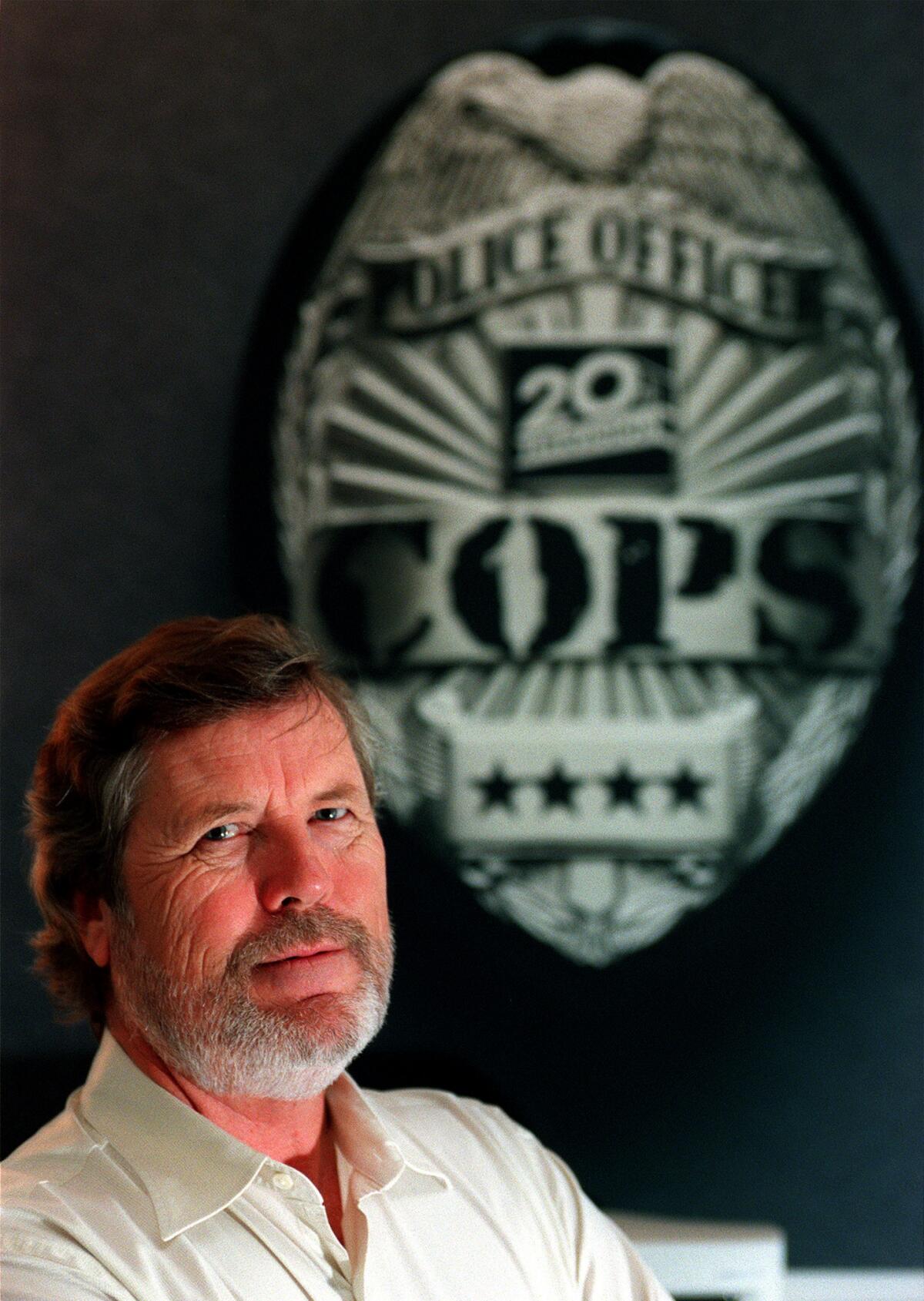

So he teamed with producer Henry Molofsky to make “Running From Cops,” a six-part podcast exploring the history and cultural impact of the longest-running reality show on American television. Featuring interviews with “Cops” creator John Langley, law enforcement officers who have appeared on the show and even people who have been arrested — many while drunk or high — on the air, “Running From Cops” offers rare insight into the making of the ride-along show, which former Times TV critic Howard Rosenberg once accused of allowing the police to “choreograph themselves as heroes.”

It also offers compelling data.

Paramount Network has canceled “Cops,” the long-running reality series following officers from various police agencies as they perform their duties.

The producers of “Running From Cops” wanted their research to be as “academically rigorous” as possible, said Molofsky. Assisted by a team of screeners, they watched and gathered data on 846 episodes of the show — roughly 82% of the series’ run to that point. For each of the three segments in every episode, they logged information, including the race and gender of the police officers and suspects, the nature of the alleged crimes, whether the suspect was inebriated and if the stop resulted in an arrest or car chase.

Molofsky estimates he watched about 300 episodes over the course of a few months. Some days he would do nothing but binge-watch the show and gather data, an experience he calls “disturbing.”

“I think all of us would have nightmares,” he said, “which was revealing.”

They ultimately collected 90,000 data points, which they compared year by year to statistics from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting in order to determine how the real world compared to “Cops.”

They found that drug crime was much more prevalent than it is in real life (35% of the crime on “Cops” versus 13% in reality), as were prostitution (5% on “Cops” versus less than 1% in reality) and violent crime (7% of the crime on “Cops” vs. 4% in real life).

The police have also become more effective over the years on “Cops.” In Season 2, 61% of segments ended in an arrest. By Season 30, the arrest rate was 95%.

“Basically, it presents a world that is much more dangerous than real life,” Taberski said. “It presents the police as being much more successful than they really are. It misrepresents crime by people of color — the raw numbers are about the same but the show front-loads crime, and especially violent crime, by people of color. And anyone who’s worked in television, especially reality television, knows that you front-load your best stuff, you hook people in the first act.”

The producers also tracked down 11 people who had been suspects on “Cops” — not an easy feat, given that few people who’ve been arrested on national television are eager to relive the experience.

“The people we found, all but one, said that they didn’t sign a release, that they were too drunk or high to know what they were doing or that they were coerced into signing by producers who were standing right next to the police officers who were the stars of the show, basically using the power of the police to coerce them into signing,” Taberski said.

Perhaps most relevant to the current conversation around the use of force by law enforcement, “Cops” also “consistently presents bad policing as good policing,” Taberski said, “by tazing people when they shouldn’t be tazing, [using] illegal holds, siccing dogs on people without the proper warning — just over and over.”

Critics say the popular TV shows of “Law & Order,” “Chicago PD” and “FBI” creator Dick Wolf create harmful misperceptions of the criminal justice system.

He cited the example of a segment in which an officer uses a flashlight to pry open a Black man’s mouth to see if he is carrying drugs. “As you’re watching it, you realize that if this was in an upper-class white neighborhood, this would not be happening. After 30 years of people watching this — myself included — it really skews your sense of what is OK and not OK for the police to do.”

The “Running From Cops” team was able to find raw, unedited footage of a seemingly routine drug bust portrayed in a 2013 episode of “Cops.” In the version of the arrest that was broadcast on the show, a teenage couple is pulled over late at night. A police officer quickly finds traces of white powder in the car. A roadside drug test determines that it’s cocaine and the kids are arrested.

In the unedited footage, the officer spent 14 minutes searching the car before finding the white substance, took three tries before getting a positive result and turned off the camera before the final test came up positive.

“The police officer denies he planted that evidence, but even if he didn’t, just the pure disparity between what they showed and what actually happened — it’s the kind of thing you expect from “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills.” I just didn’t expect it to be quite so egregious and cruel,” Taberski said.

“Running From Cops” also looks at the phenomenon of “Live PD,” a hit reality show on A&E that took the “Cops” formula to the next level by following police officers as they make arrests in quasi-real time — the segments are made to seem live but air with a delay of several minutes, and some are pre-taped.

It was canceled Wednesday, following news that a “Live PD” crew filmed the death of a 40-year-old Black man who died in police custody and the footage was destroyed by the network. But the network seemed to leave open the possibility it would return in a revised format.

While proponents of shows such as “Cops” and “Live PD” emphasize the “transparency” they bring to law enforcement, producers are dependent on the cooperation of police departments, and thus unlikely to portray them in a critical light, said Taberski, a former field producer on “The Daily Show” who also co-created the reality show “Destroy Build Destroy.”

“Any TV producer will tell you, they can’t do things that are gonna piss off their subjects because they need access. They can’t make their show without police cooperation and the police aren’t gonna cooperate unless you show a good version of what they do,” he said.

The cable hit ‘Live PD,’ which followed officers from cities across the U.S. in real time, was canceled amid protests over police brutality.

“Cops” and shows like it help also burnish the public image of the police by making the job itself seem more exciting than it sometimes is — there are few “Cops” segments about directing traffic or filling out incident reports.

“Anecdotally, the number of cops on the show who say they wanted to become a police officer because they watched ‘Cops’ was pretty telling,” said Molofsky. “We’ve talked to the police departments that participate and they say straight-up they use it for recruiting — that they can’t pay as much as they used to and have recruiting shortages, but these shows drive up recruiting.“

“Cops” regularly stoked controversy throughout its three-decade run.

Co-created by John Langley, the series premiered in 1989, after a writers’ strike that had left networks hungry for new content to fill their schedules. Fox, then a brash upstart, was looking to replicate the runaway success of “America’s Most Wanted,” the true-crime docuseries hosted by John Walsh. It became a major hit and, in early seasons, turned local cops into reality TV stars. (Langley did not respond to The Times’ request for comment.)

Critics have long maintained that “Cops” exploits poor people and drug addicts, violates the privacy of suspects and perpetuates the idea that people of color are more likely to commit crime. It was even at the center of a Supreme Court case in the 1990s.

Spurred by the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012, the advocacy group Color of Change organized a successful campaign to get Fox to cancel the series, which remained a solid ratings performer. It was immediately picked up by Spike — a cable network catering to young men that was later rebranded as Paramount Network.

Taberski hopes that television has reached a turning point and that shows like “Cops” and “Live PD” are a thing of the past.

“There’s a part of me that feels bad saying that because I know people work on these shows. But then when you see the people that have been victimized by these shows, just like countless numbers of people put on TV without their consent, often shown doing things they didn’t do or just invading their privacy in what could be potentially a really dark moment in their lives. There’s no reason for it, there’s no excuse for it and it just shouldn’t be happening.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.