Stanford to show Little Bighorn drawings by Red Horse, a Native American artist in the fight

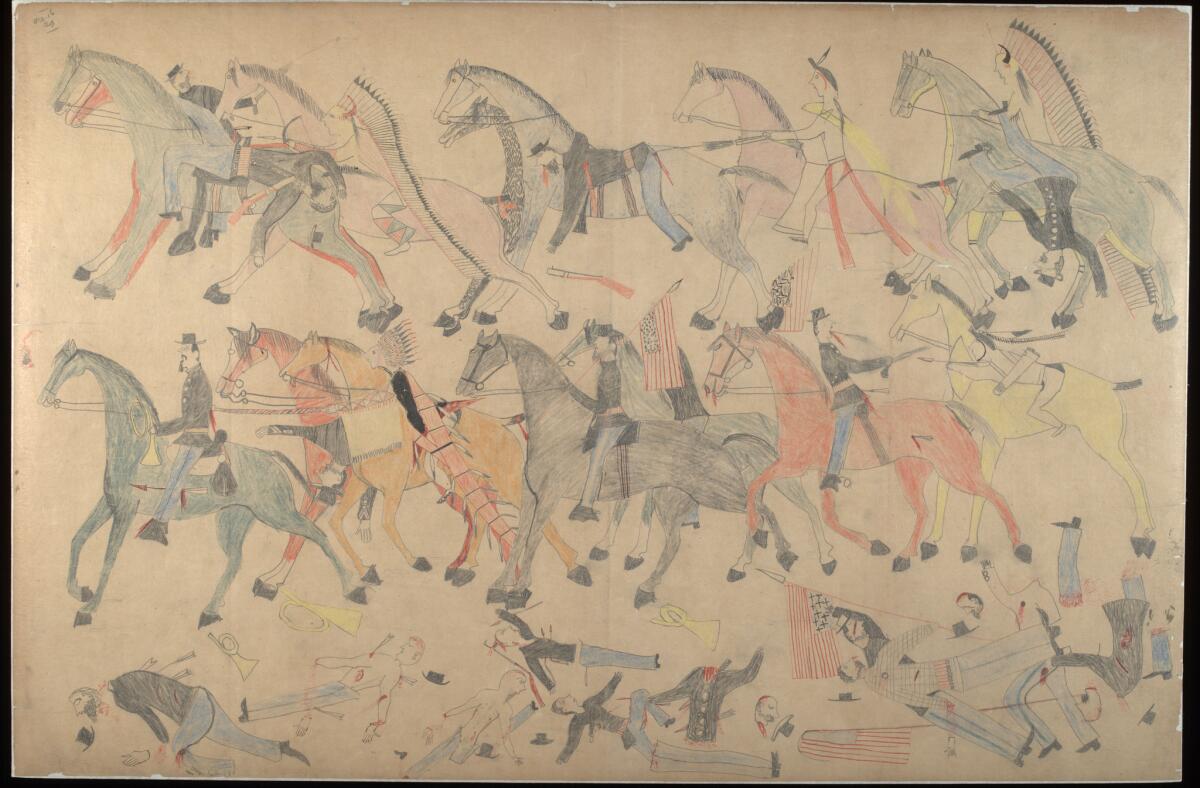

A scene from the Battle of the Little Bighorn drawn by Red Horse, a Lakota Sioux chief who fought in the battle. It’s one of a dozen drawings that will be shown in an exhibition at Stanford University, picked from the 42 that Red Horse created from memory five years after the 1876 battle.

- Share via

There’s no lack of visual impressions of the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

One is dashing Errol Flynn valiantly leading his men to their doom in black and white in “They Died With Their Boots On,” a film that, quite contrary to the historical record, depicted George Armstrong Custer as sympathetic to the Native American tribes he fought.

Arthur Penn’s acidly antiheroic view of the battle in the film “Little Big Man” shows Custer lapsing into an insane fantasy on the battlefield. An arrow ends the dandified general’s megalomaniacal raving just as he’s about to shoot wounded cavalryman Dustin Hoffman in the head.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

But perhaps the most important and reliable visual record of June 25, 1876, comes from someone who was there: Red Horse, a Lakota Sioux chief who, drawing from memory five years after the fighting, used colored pencils and manila paper to create a suite of 42 unsparing images chronicling the horrific battle in which he’d fought.

A dozen of the drawings from the “Red Horse Pictographic Account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn” will leave their usual repository at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Anthropological Archives in Washington, D.C., and go on display Jan. 16 to May 9 at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center.

The Cantor’s announcement of the exhibition Wednesday said it’s the first time a representative selection of these works has been displayed together since 1976, when the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery put on the exhibition “Keep the Last Bullet for Yourself: The Fight at Little Bighorn.”

A Smithsonian publication from June 1976 described it as “a small show” timed to the battle’s 100th anniversary. Also on display were Custer’s buckskin coat and battle flag and the last message he sent before making his last stand. Custer rode into battle after dividing his Seventh Cavalry into three groups, aiming to encircle an Indian encampment along the Little Bighorn River in what’s now Montana. Instead, a vastly superior force led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse attacked, and the unit Custer led was wiped out.

For the record, Nov. 6, 12:30 p.m.: an earlier version of this post incorrectly said that the battle site is in South Dakota, rather than Montana.

Jake Homiak, director of the Anthropology Collections and Archives at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, said Wednesday that, to his knowledge, only three of Red Horse’s drawings previously had been loaned for display outside the Smithsonian.

The coming show springs from a sophomore seminar course at Stanford called the Face of Battle, in which political science professor Scott Sagan, borrowing the title from a celebrated book by the British military historian John Keegan, tries to give students a sense of what warfare is like for the combatants themselves. He uses Gettysburg and Little Bighorn as case studies. Students travel to both battlefields as part of their classwork, and Sagan also brings them to the Smithsonian to see Red Horse’s drawings and discuss their meaning with JoAllyn Archambault, director of the American Indian Program at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Sagan said by email that he and two collaborators from Stanford picked the dozen drawings “for both aesthetic and pedagogical reasons. These drawings are both emotionally powerful and representative of the chronology of the battle.”

W. Richard West Jr., president of the Autry Museum of the American West, said he would love to develop an exhibition around Red Horse’s drawings -- if the Smithsonian proves willing to let the delicate works travel again after the Stanford show.

“I think it’s remarkable that they have assembled these, and I’m just delighted they’ve done this,” said West, whose southern Cheyenne great-grandfather, Thunder Bull, was a teenaged combatant at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. (West proudly points out that, while most of the Indians in the fight were Sioux, the Cheyenne were part of the allied force and “we consider ourselves the elite corps of the Little Bighorn.”)

“It’s a gem of an exhibition and a gem of an idea,” West said, because the show will come at the Red Horse drawings from varied perspectives of art history, military history and Native American culture.

West said Red Horse’s drawings are not the only eyewitness artworks depicting the battle, but “it’s fair to say it’s one of a kind because of their quality, detail and size.”

By 1881, Red Horse was living at the Cheyenne River Agency, a reservation in South Dakota, where a U.S. Army doctor, Charles McChesney, asked him to draw the Battle of the Little Bighorn from memory.

The works are part of a genre called ledger drawings, created in the late 1800s by Native American artists who repurposed paper from blank ledgers used by businesses and tradespeople in the West. Red Horse’s drawings are about 2 feet high and 3 feet long.

West said Native American artists who did ledger drawings simply were making use of the materials at hand to continue a traditional form of pictorial accounts of historic events that previously had been done on surfaces such as buffalo hide.

The Autry owns two depictions of the Battle of the Little Bighorn done on muslin by Native American veterans of the fight: an 1890 drawing and watercolor by White Swan, a Crow tribesman who was there as a scout for the Seventh Cavalry, and an 1898 painting of the corpse-strewn aftermath by Kicking Bear, done at the request of the artist Frederic Remington. It’s on display in the Autry’s exhibition “Empire and Liberty: the Civil War and the West.”

The drawings by Red Horse include vivid action scenes from the heat of battle, as well as pictures of the terrible aftermath -- drawings devoted separately to slain Indians, slaughtered horses and dead cavalrymen stripped of uniforms that became the spoils of battle.

The most triumphant images show the victors chasing or leading away their most prized booty: the cavalry horses that survived. In one remarkable battle scene, two American flags hang upside down from the lances of fallen U.S. soldiers.

Red Horse’s 12 drawings will have a gallery of their own at the Cantor Arts Center, Sagan said, augmented nearby by contemporary Native American art and other pieces that are being chosen by Sarah Sadlier, a Stanford senior who took his the course two years ago and became the exhibition’s research assistant. She has a personal as well as a scholarly connection: She’s a member of the Minneconjou band of the Lakota Sioux, the same branch as Red Horse, and one of her ancestors was an interpreter for Sitting Bull.

Follow @boehmm of the LA Times for arts news and features

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.