Screenwriter struggled to transform ‘Big Fish’ into Broadway musical

NEW YORK — Recently, writer John August watched a DVD of “Big Fish,” the 2003 film directed by Tim Burton for which he wrote the screenplay.

He says it was an enjoyable but odd experience.

“I kept wondering, ‘Why aren’t they singing?’” recalls the 43-year-old screenwriter with bemusement. He has been working on adapting the material for the musical stage for the past nine years — four more than it took him to write the film.

There are now songs — plenty of them — in August’s book for “Big Fish,” a collaboration with composer Andrew Lippa and director-choreographer Susan Stroman that opens Sunday on Broadway.

One of the most highly anticipated musicals of the season, the $14-million “Big Fish” is one of the many stage musicals hoping to extend the life of the movies on which they are based.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

If the producers are willing, some of the films’ writers try to make the transition — August, Woody Allen with “Bullets Over Broadway,” Andrew Bergman with “Honeymoon in Vegas” — and some do not. Veteran librettist Tom Meehan is adapting “Rocky,” for example, not Sylvester Stallone. Marsha Norman has adapted “The Bridges of Madison County,” not Richard LaGravenese.

And as more and more films are becoming Broadway source material, the graveyard is littered with musicals in which screenwriters have proved incapable of separating themselves from their original scripts to meet the demands of the stage.

Although the book is often blamed for an unsuccessful show, whether it’s by a

screenwriter or not, such high-profile failures as “9 to 5” and “Ghost” call attention to pitfalls for a theater outsider who created it for a different medium.

A number of Broadway-bound musicals adapted by their respective original writers have run into development trouble. After postponing its announced Toronto tryout last year, Bergman’s “Honeymoon in Vegas” is in its world premiere engagement at the Paper Mill Playhouse in New Jersey. Barry Levinson’s adaptation of “Diner,” with music by Sheryl Crow, appears to be in limbo after numerous postponements.

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

“The temptation is to be very literal to what you did before because that’s what worked,” August says. He didn’t watch the movie or refer to the script while he was working on the musical.

“I didn’t want the choices to be made for the wrong reasons. The right choice was to look for those moments that could be transcendent because they were onstage, not because they could be translated from film,” August says.

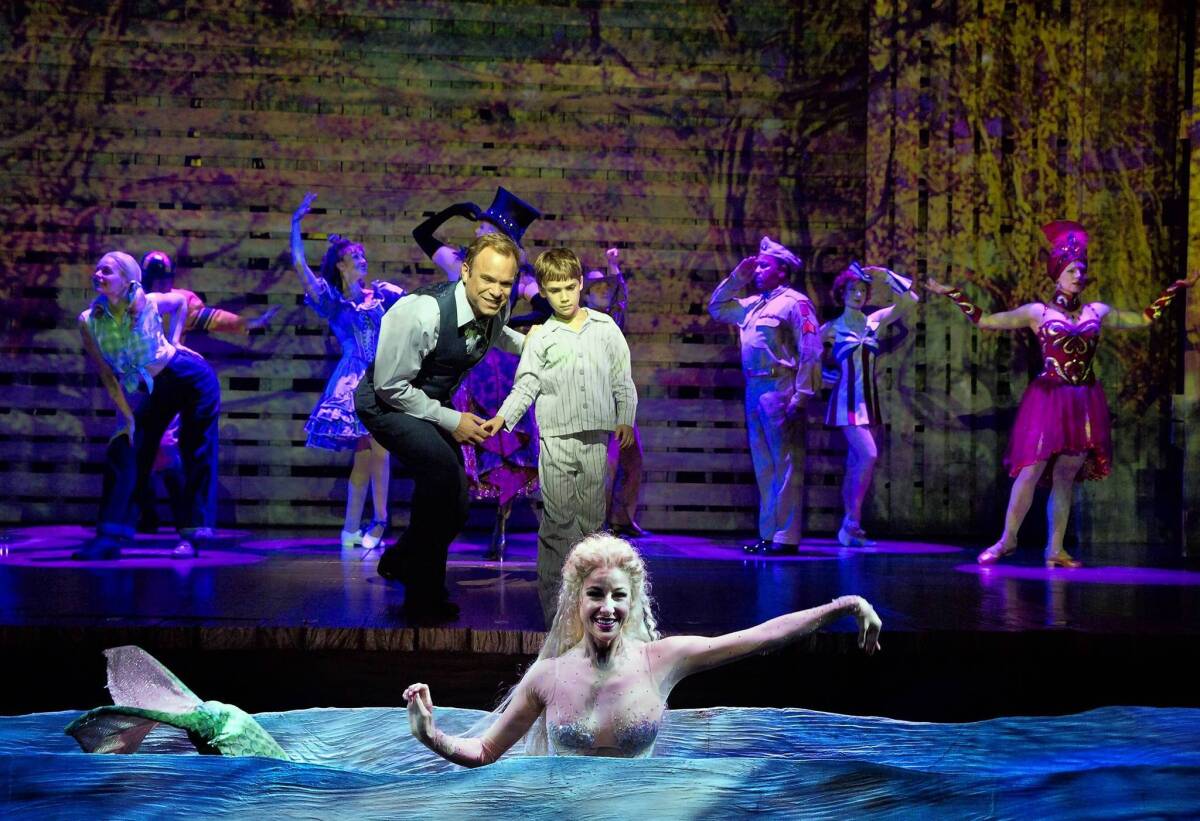

“Big Fish,” based on a novel by Daniel Wallace, is a bittersweet family drama about Edward Bloom, a blustery Southern fabulist who spins heroic tales of encounters with a witch, a mermaid, a giant, a werewolf, and assorted freaks and evildoers.

At first, these fantastical stories enchant his son, Will, but eventually he becomes estranged. Sandra, the mother and wife, tries to help bridge the gulf between father and son when Edward is diagnosed with a terminal illness.

August remembers a test screening of the film in Orange County in 2003, when he approached the producers Bruce Cohen and Dan Jinks and told them the characters “sang” to him. “I think we should try to turn this into musical, but I don’t know where to start,” August says.

That was not entirely the case. He’d written “Corpse Bride,” an animated musical, and “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” for Burton. Even in the film of “Big Fish,” he’d written lyrics for a Danny Elfman tune, “Twice the Love,” sung by the Siamese twins Ping and Jing.

But August had never before written a musical for the stage. “I had a pretty good sense of the vocabulary for it but had not been steeped in it,” he says.

Cohen and Jinks, who won the Oscar for “American Beauty” and are lead producers on the musical, put August together with composer Andrew Lippa (“The Wild Party,” “The Addams Family”). For the first five years, the two hashed out the parameters of the musical, throwing out scenes and characters from the film without hesitation.

Lippa says that August’s attachment to his screenplay was “very little.”

Ultimately, the musical would retain less than 5% of actual dialogue from it.

“What’s remarkable about John was that he’d already spent five years with these characters and yet he was very open to fleshing them out,” Lippa says. “He wasn’t used to collaborating, but he was very aware that he couldn’t write scenes the way he was used to writing them.”

Among the first and most crucial decisions was to have Edward, who ages from 16 to 65 in the show, played by one actor, two-time Tony winner Norbert Leo Butz. In the film, the character was divided between Ewan McGregor and Albert Finney.

Likewise, Sandra, who in the film was played by Alison Lohman and Jessica Lange, is here performed by Kate Baldwin. The creative team believed they could get away with it not only because of the acting talent involved but because audiences come to the theater willing to suspend disbelief.

How best to take advantage of that was a lesson he learned, August says.

“In movies, everything is a photograph, even if you’re being abstract,” the screenwriter says. “In theater, it’s more representational. That corner of the garage is the whole Bloom house. Your brain gets more excited to fill in the details. This works very well for a story about a storyteller because it’s all about suspending disbelief and going along for the ride.”

Greasing the wheels of that ride is Stroman, who signed onto the project two years ago after being presented the material by August and Lippa. One of the acknowledged masters of the musical form — she’s also directing and choreographing “Bullets Over Broadway” this season — the Tony-winning director was exacting in that every beat had to be “theatrical,” says August, adding that she found fault with a traveling salesman number written for Butz.

“She said, ‘There’s nothing ‘Big Fish’ about it, give me something larger than life,’” August says.

August and Lippa, knowing that Stroman had filled her chorus with a number of strong, tall women, came up with a splashy USO number that sends Edward off to save the world from an evildoer.

The challenge came in the double-track nature of the musical: the linear story of a man facing death and reconciling with his son and the fantasy sequences that could threaten “to float away” if not moored to the central story.

“The present day always had to be pushing forward, how they were to come together,” August says. “The fantasy numbers had to help answer that question or complicate that question. We had to integrate those two worlds without ‘cut to’ or post-production to rely on. But the limitations of stage force you to resolve those problems with the most interesting answers.”

One way they were able to do that was by keeping Will, played by Bobby Steggert, in the fantasy sequences, a grounded character whose presence tips off the audience that he is trying to comprehend his father’s stories to understand the man himself.

It was also this character who underwent the most substantive change between the tryout in Chicago and the beginning of previews in New York.

There was a sense among the creative team that the beginning of the musical was flawed. The contentious relationship between father and son got “too heated, too fast,” says August about a song, “This River Between Us,” which paralleled a wedding scene at the beginning of the film in which Edward marginalizes Will at his own wedding by telling a long story to the assembled guests.

“Will, whose wife is pregnant, needed a song that spelled out why he was acting in the way that he was, that was an insight into his character,” August says.

In the basement of the Oriental Theatre in Chicago, Lippa and August sketched out a new scene and song, “Stranger,” that expressed Will’s inner torment about Edward as he himself was facing fatherhood. In thinking about his child, he could resolve to understand his father in a more positive way.

“It’s a vast improvement from what was on film, I don’t know how we could have done it then without a song,” says August, who also thinks several of the relationships in the show are stronger than in the film because they have been set to music. “If I could go back and rewrite the movie, there’s a lot of things that I would do differently. Because I’ve had nine more years to work on it.”

Given the endless recycling of Hollywood, it’s not unlikely that August may one day have a chance if “Big Fish” is a success. After all, film versions of stage musicals are increasingly common these days.

“I’d love to have that chance, but that’s probably way down the road. I don’t doubt that I will probably be writing some version of ‘Big Fish’ for the rest of my life, even if it’s the Ukraine trapeze version of it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.