Review: Time and space are one in thrilling ‘Einstein on the Beach’

There is an anecdote about Einstein from when he taught at Caltech in the early 1930s. One day, pianist and Beethoven specialist Artur Schnabel came to visit the famed physicist, who was an avid amateur violinist, and they read through a Beethoven violin sonata. It didn’t go well. Fumbling a tricky rhythm, Einstein got lost, and Schnabel exclaimed in frustration, “Albert, you can’t count!”

I have no idea how true this is (there are variants of the story), but what matters is that 80 years later, Einstein counted at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, and it was a momentous event. After decades of various failed efforts to locally mount “Einstein on the Beach” — the revolutionary and by now legendary 1976 experimental American opera by composer Philip Glass and director and designer Robert Wilson — Los Angles Opera finally, and heroically, succeeded Friday night.

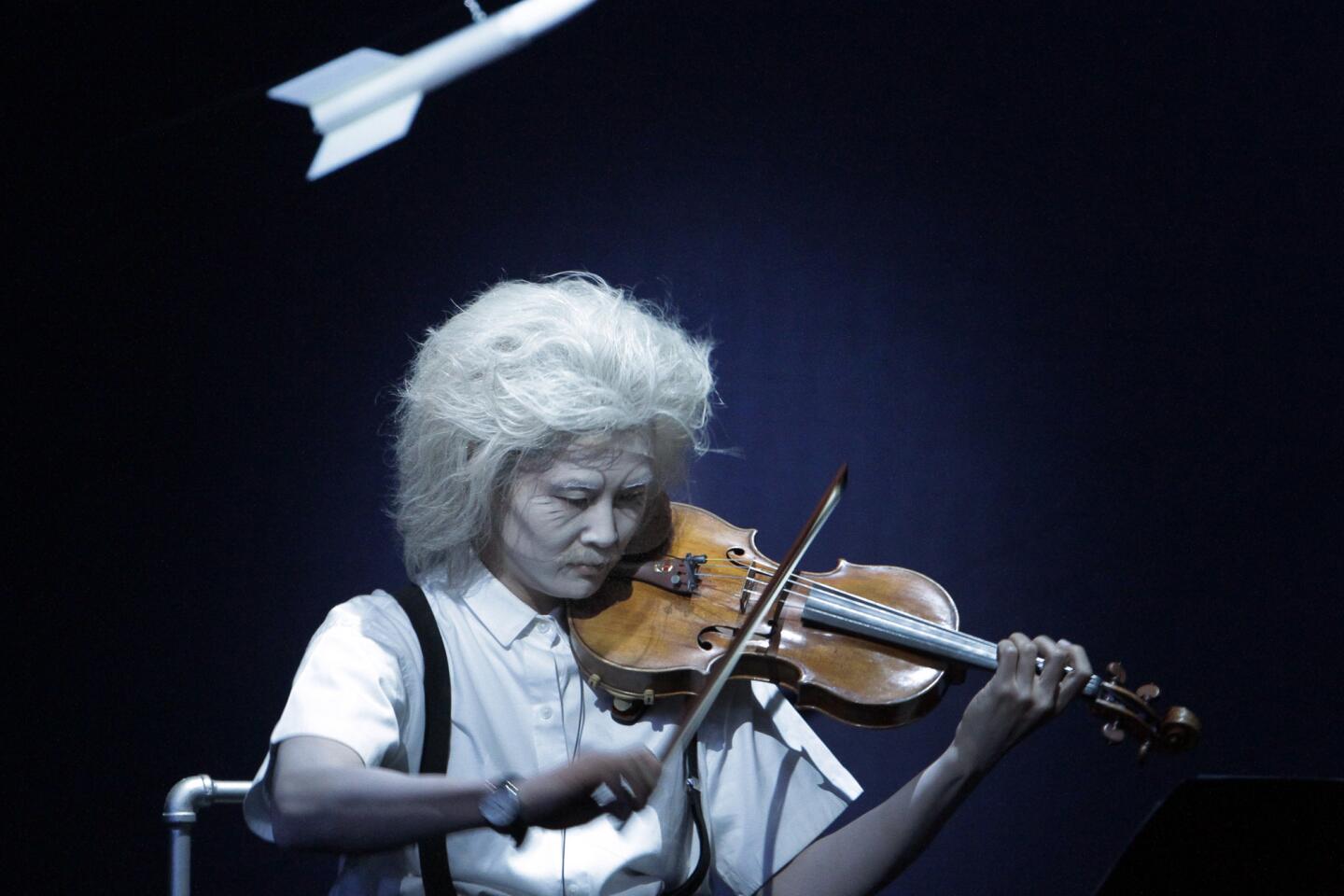

The performance began with a small chorus of Einsteins counting out the rhythms of repeated pitches — 1, 2, 3, 4; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 — accompanied by the long-held organ bass notes F, G, C. Nothing could be more elemental, the building blocks of music here operating like the primary elements of the universe.

PHOTOS: Operas by Philip Glass

Four ecstatic hours later, the universe having been unveiled in rapturous music and imagery and movement, the Einstein chorus was back, counting again over that that same bass line. A speech about love was read. All seemed ineffably right with the world. When Glass, Wilson and choreographer Lucinda Childs came out to take a bow, they received one of the most thrilling, thunderous ovations in the history of L.A. Opera.

This “Einstein” — the first revival in 20 years — originally was mounted last year by its creators for a world tour. Its success last fall in Berkeley is what motivated L.A. Opera, with an assist from the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA, to bring it to the Music Center, which was thought to be the final destination. Glass, Wilson and Childs, all in their 70s, have said this will be the last time they will be involved in putting on “Einstein,” and the world understandably seems not to want to let the show go. So now Paris will get it in January and possibly Berlin in February. A commercial video — its first —- may be in the offing.

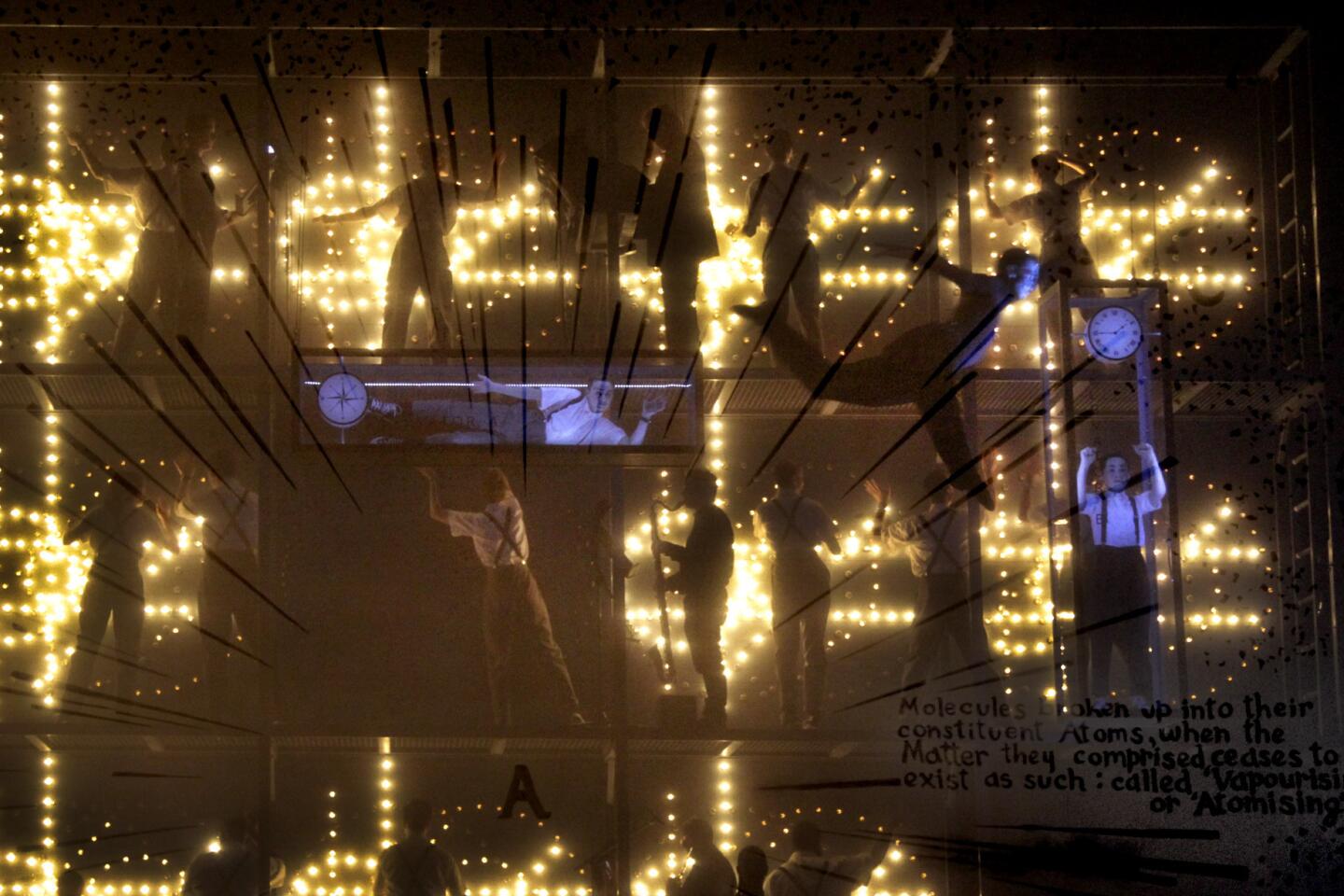

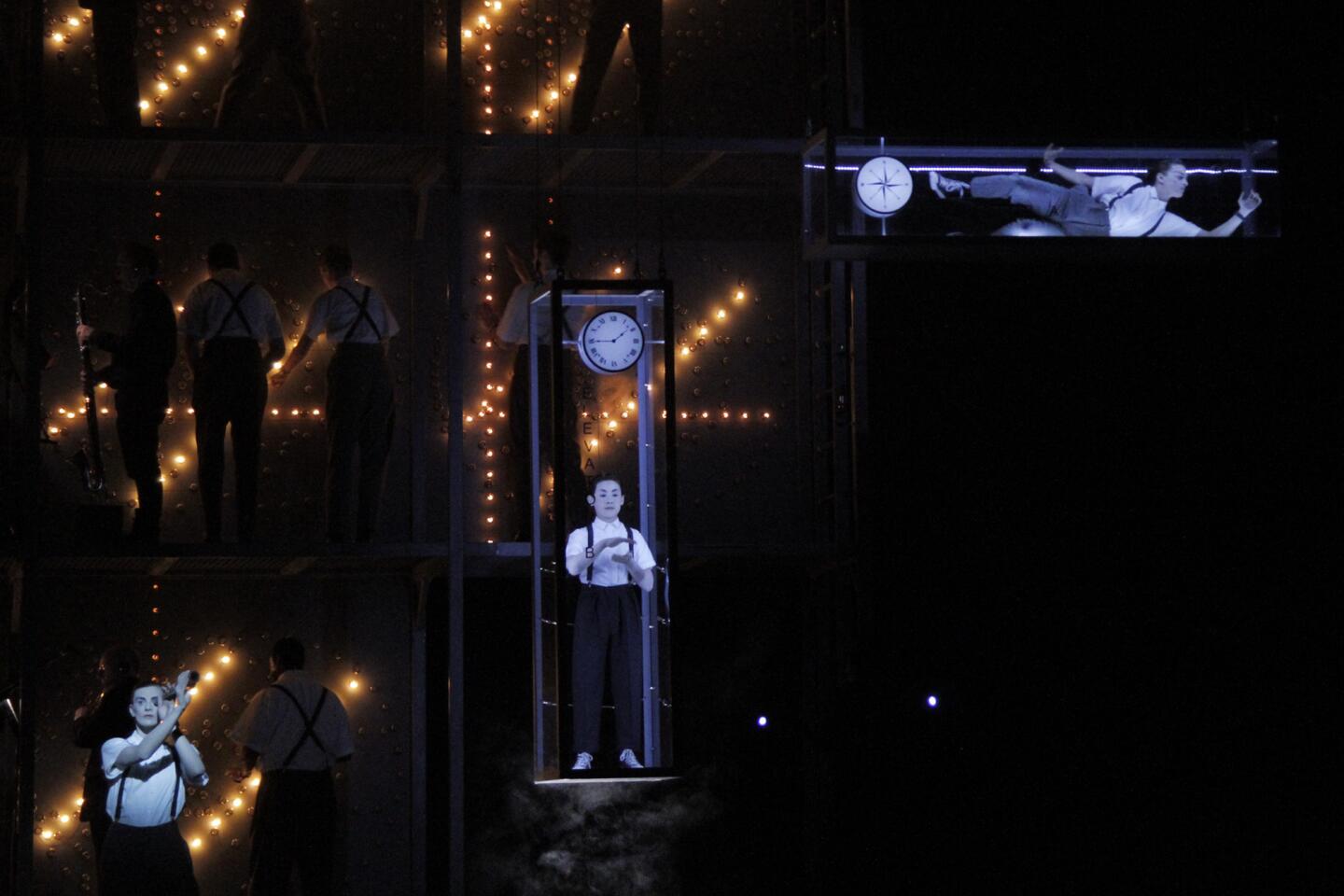

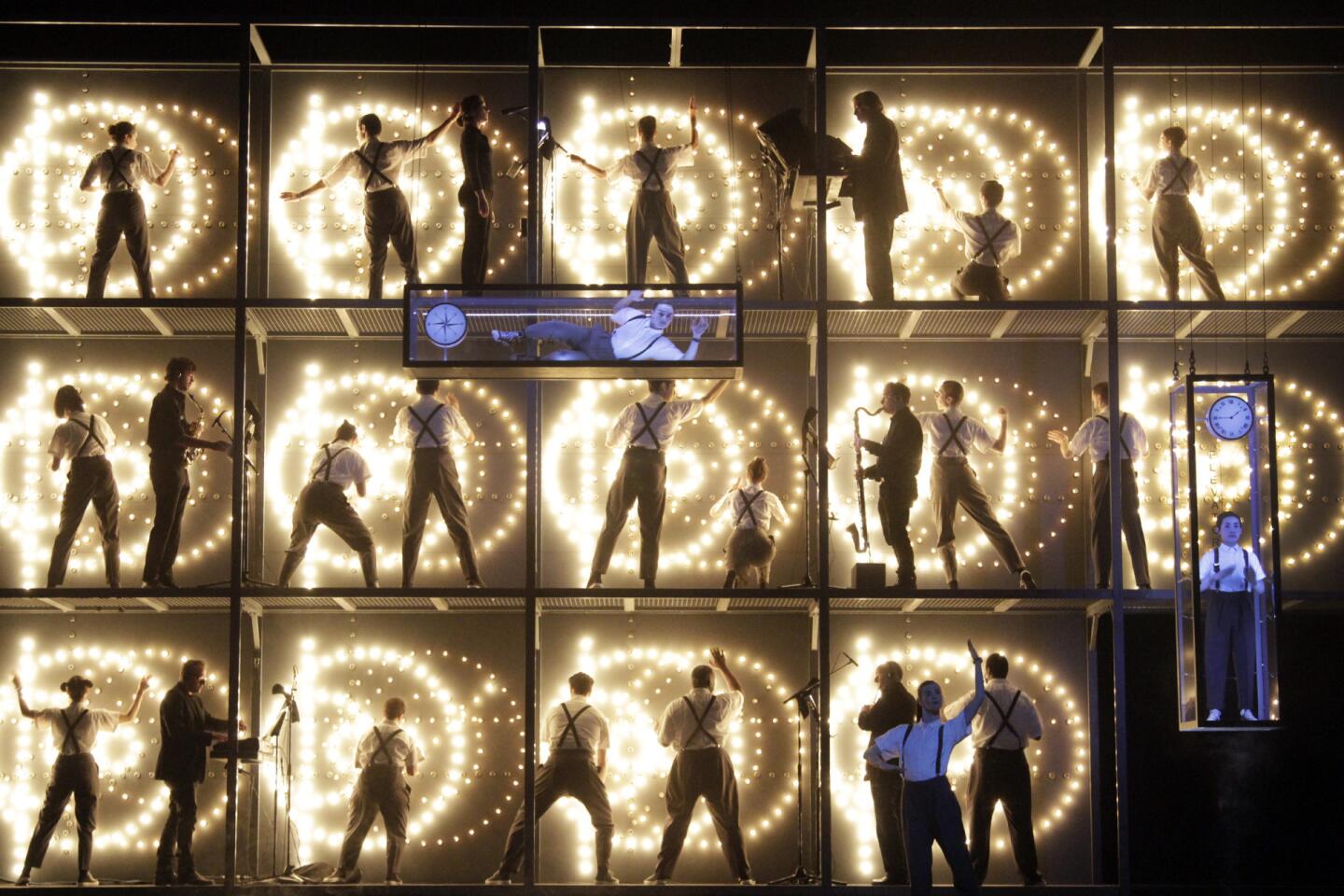

Descriptions cannot do “Einstein” justice, and explanations are inappropriate. Presented over four hours without a break, the opera is in four acts, introduced, connected and concluded by five joining entr’actes that Wilson calls “knee plays.” The work is not narrative but image-based. You enter “Einstein” and let it take over your senses.

The scenario, for maybe the first time in the history of opera, is a series of Wilson drawings that are transferred into a glowing reality onstage. Many relate to Einstein’s life and world. Light, most of all, has essential meaning for Einstein and Wilson. A train and spaceship are proper Einsteinian objects, and they are fetishized in wondrous ways. A glowing conch shell gets its symbolism, Wilson has said, from Newton, who claimed that you could hear the universe in a seashell.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

But it is best not to worry too much about what any of this means, because above all Einstein is ceremony, and for its fans an almost religious one.

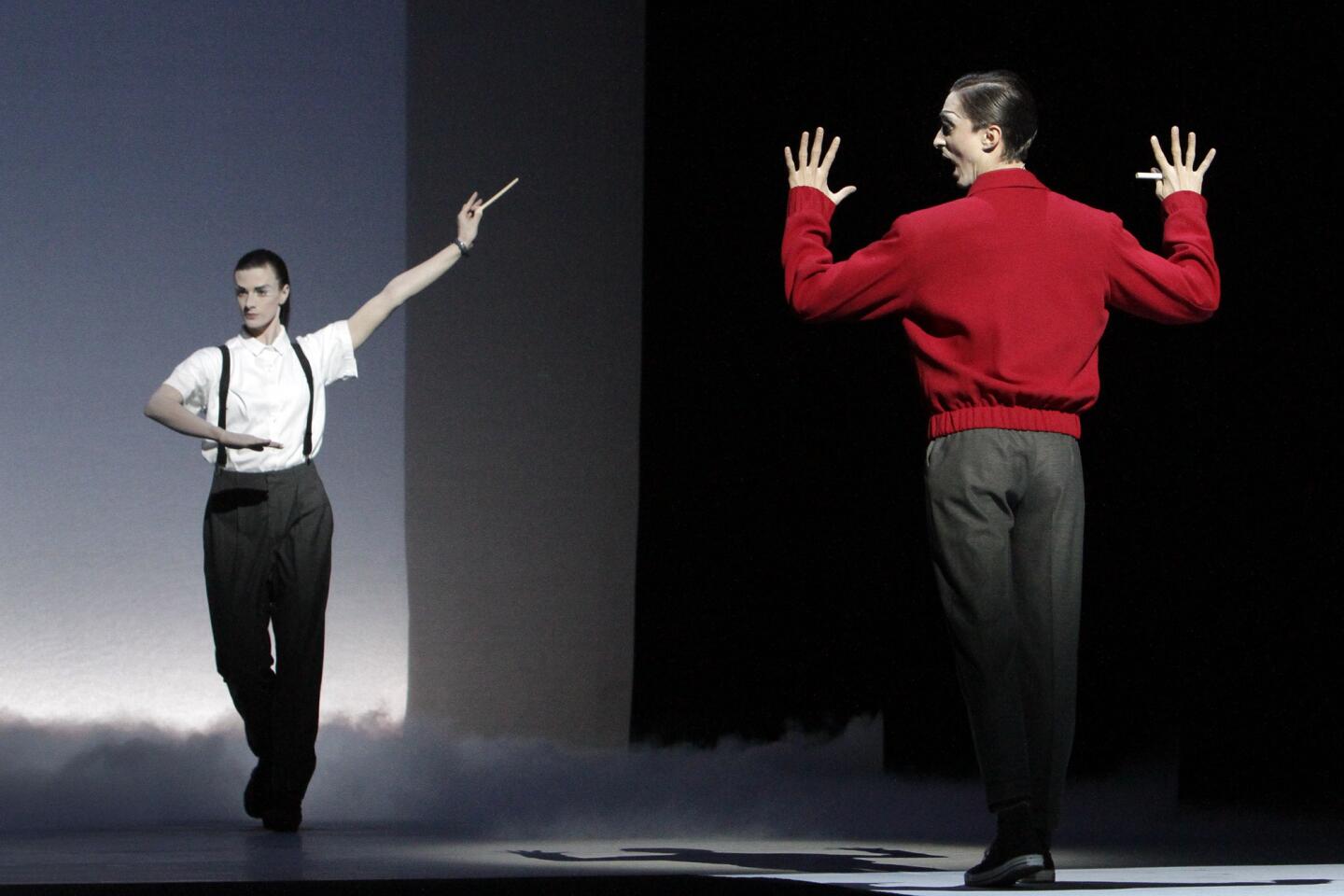

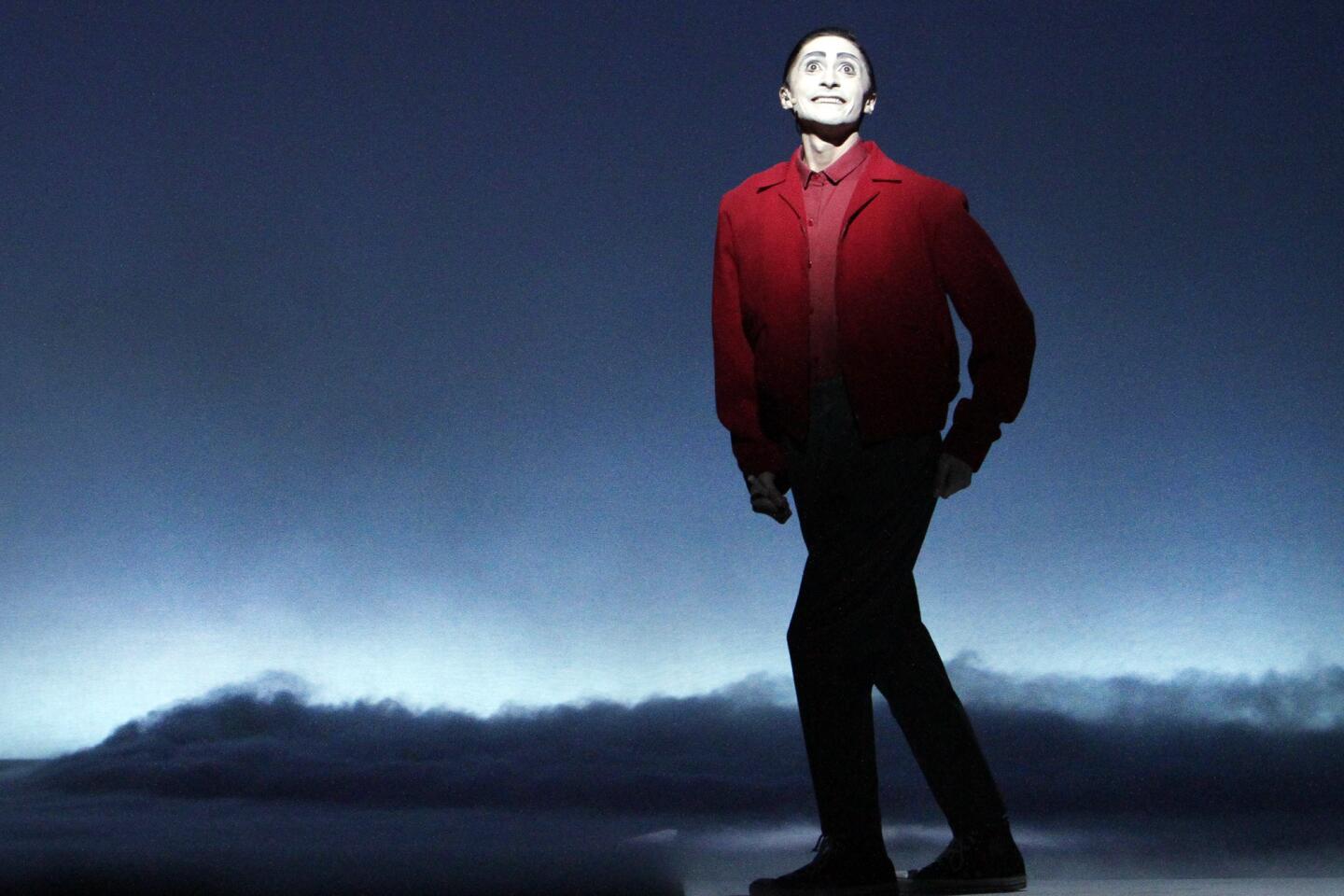

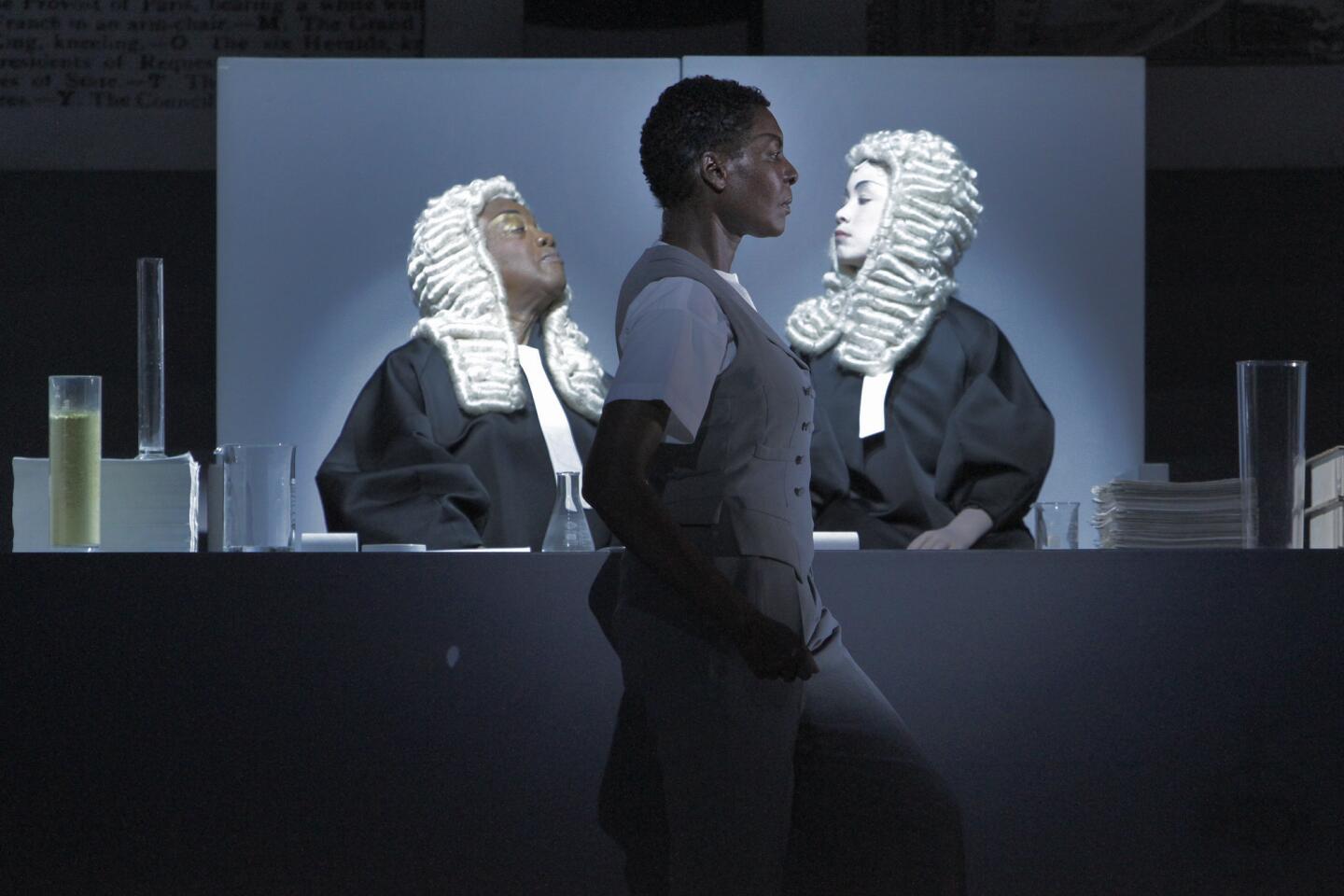

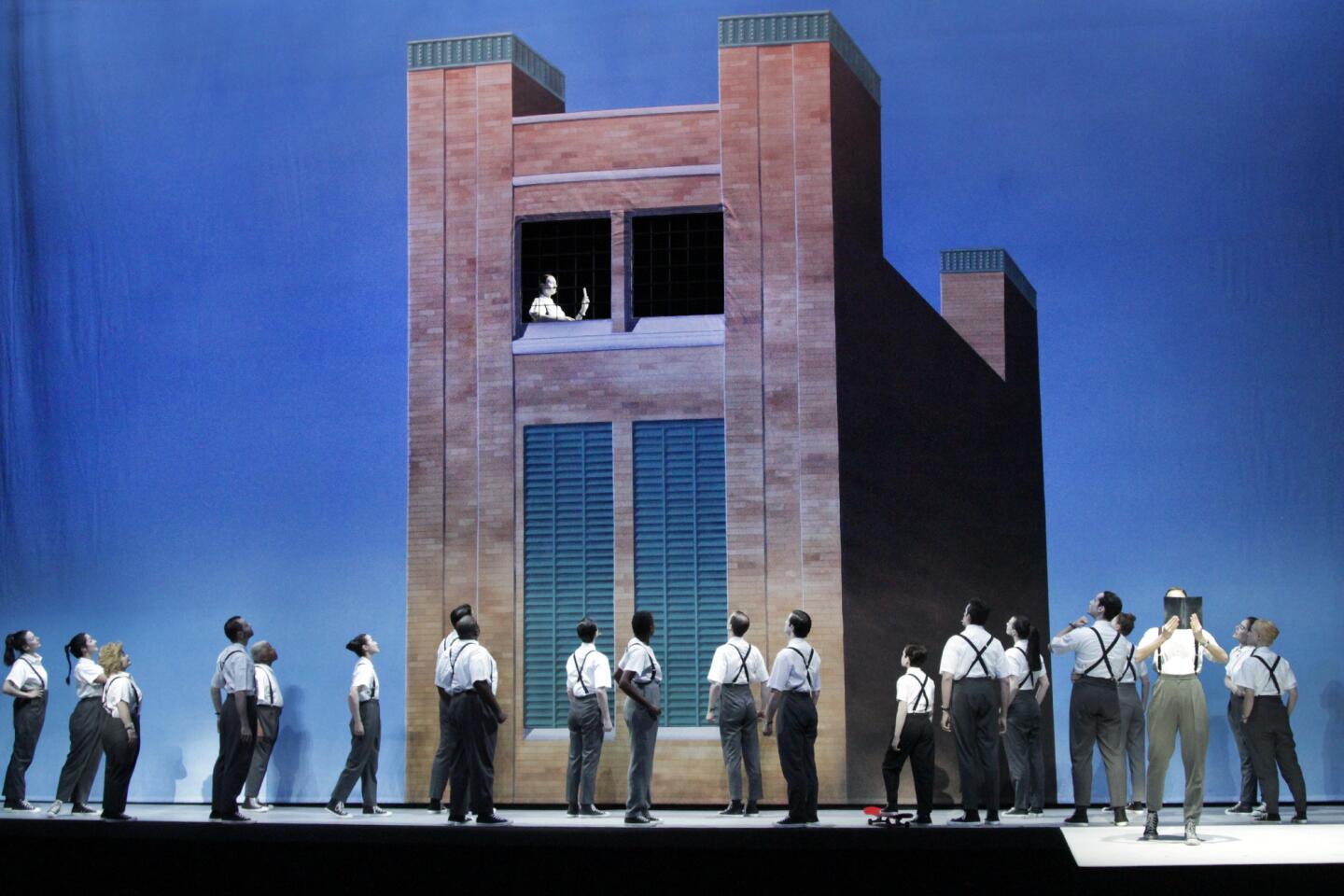

Sight and sounds of everyday life become holy. Characters — everyone is dressed in the white shirt, baggy pants, suspenders and sneakers that the physicist wears in a well-known photo — are us. There is a judge, a boy, various people you might see on the street. Patty Hearst, who was in the news when the opera was being made, makes an appearance. Why not?

Like nature, “Einstein” has its logical side and its illogical one. The overall structure is rigorously laid out, with scenes of a train, a bed, a building, a field, a space machine. Two scenes in the field, one with a doughnut-shaped flying saucer in the distance and one closer up, contain formal Childs’ choreography, her dancers racing and whirling as if propelled by Glass’ exuberantly Minimalist yet complex and virtuosic score.

There are spoken texts, many stream-of-consciousness, written by a young Wilson protégé, Christopher Knowles, and certain phrases, such as “Would it get some wind for the sailboat,” stick. (Einstein was a sailor.)

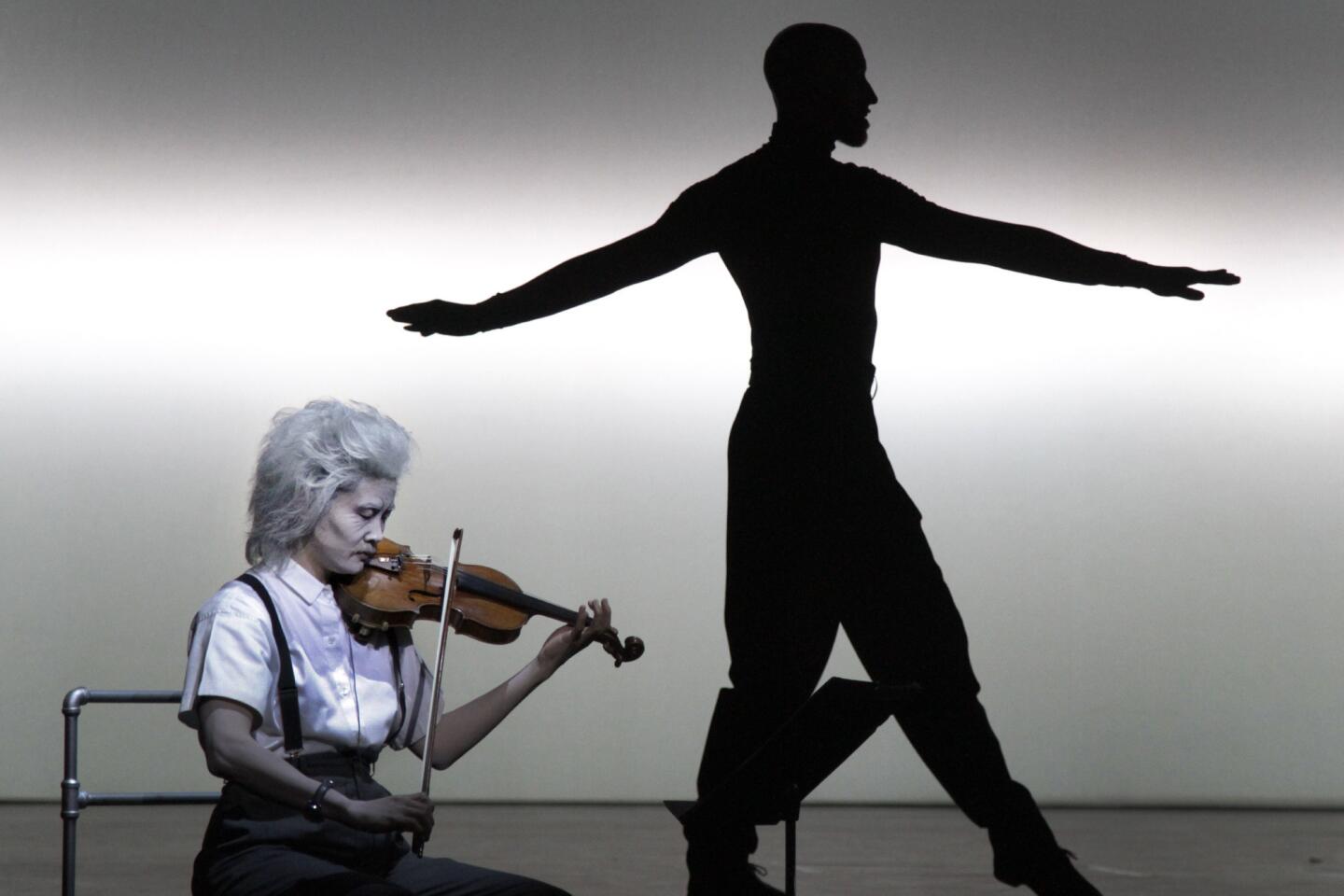

Einstein’s violin is, of course, prominent in solos that were played here, as in Berkeley, with visceral intensity by Jennifer Koh. Glass’ six-person ensemble and the chorus, moreover, demonstrated a speed and sonic depth that made the theory of relativity seem as if it were all about sound

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview

Wilson populates the stage with unforgettable presences. That was especially true with Helga Davis and Kate Moran, who recited Knowles’ text during the knee plays (which are presented in a small rectangle of light at one end of the stage). But credits go to a great many onstage and off, including conductor Michael Riesman. In my long experience with “Einstein,” it has never looked or sounded this great. Next year will be the Chandler’s 50th anniversary. “Einstein” will go down as one of its highlights.

In “Einstein,” as in Einstein’s theories, time and space are one. Only here, you don’t need to know why, you just know it’s true.

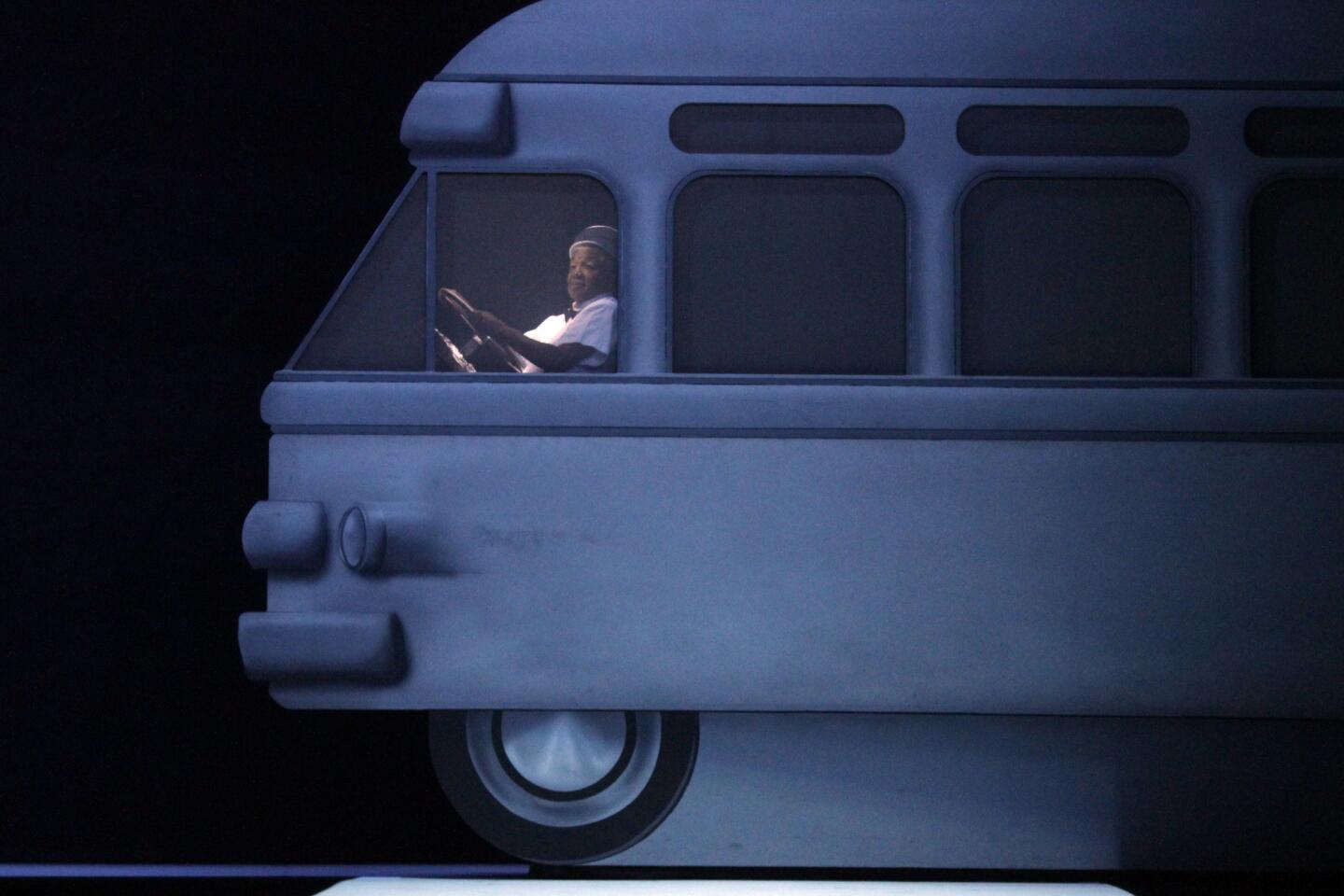

But maybe the most startling revelation is the final one, after a spectacular spaceship scene and an acknowledgment that the pacifist Einstein also paved the way for the atomic bomb. It is that final knee play with its startlingly sweet speech, delivered by a bus driver, about two lovers on a park bench in the moonlight finding love the one thing in the universe that cannot be measured.

“Everything,” one lover says to the other, “must have an ending, except my love for you.”

But what of “Einstein on the Beach”?

At a talk in Royce Hall at UCLA on Saturday afternoon, Glass, Wilson and Childs were asked how they would feel about others attempting to either re-create this original production or maybe do something new with it.

All agreed that that would be fine.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.