Jordi Savall connects cultures in ‘Bal-Kan: Honey and Blood’

Master of the viol, Jordi Savall is also a master joiner.

His specialty is a narrow-seeming one, his six-stringed instrument’s heyday having been the 16th and early 17th centuries when the viol was second in popularity only to the lute. Viol repertory is fertile, to be sure, but limited in historical scope and relevance (the Renaissance and Baroque eras), in sound (it is a quiet instrument), in tone (it has a dark, subdued character) and in geography (Western Europe).

Yet Savall, who is Catalan and who founded and conducts the outstanding period-instrument ensemble Hespèrion XXI that will be appearing Sunday in Walt Disney Concert Hall, has what could be the broadest vision among any musicians today of how cultures connect and the historical significance of that for a modern, changing world.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

More extraordinary yet, he happens to be accomplishing this in part through a one-man industry, unique in the history of recording, intent on saving the CD with the help of the coffee table.

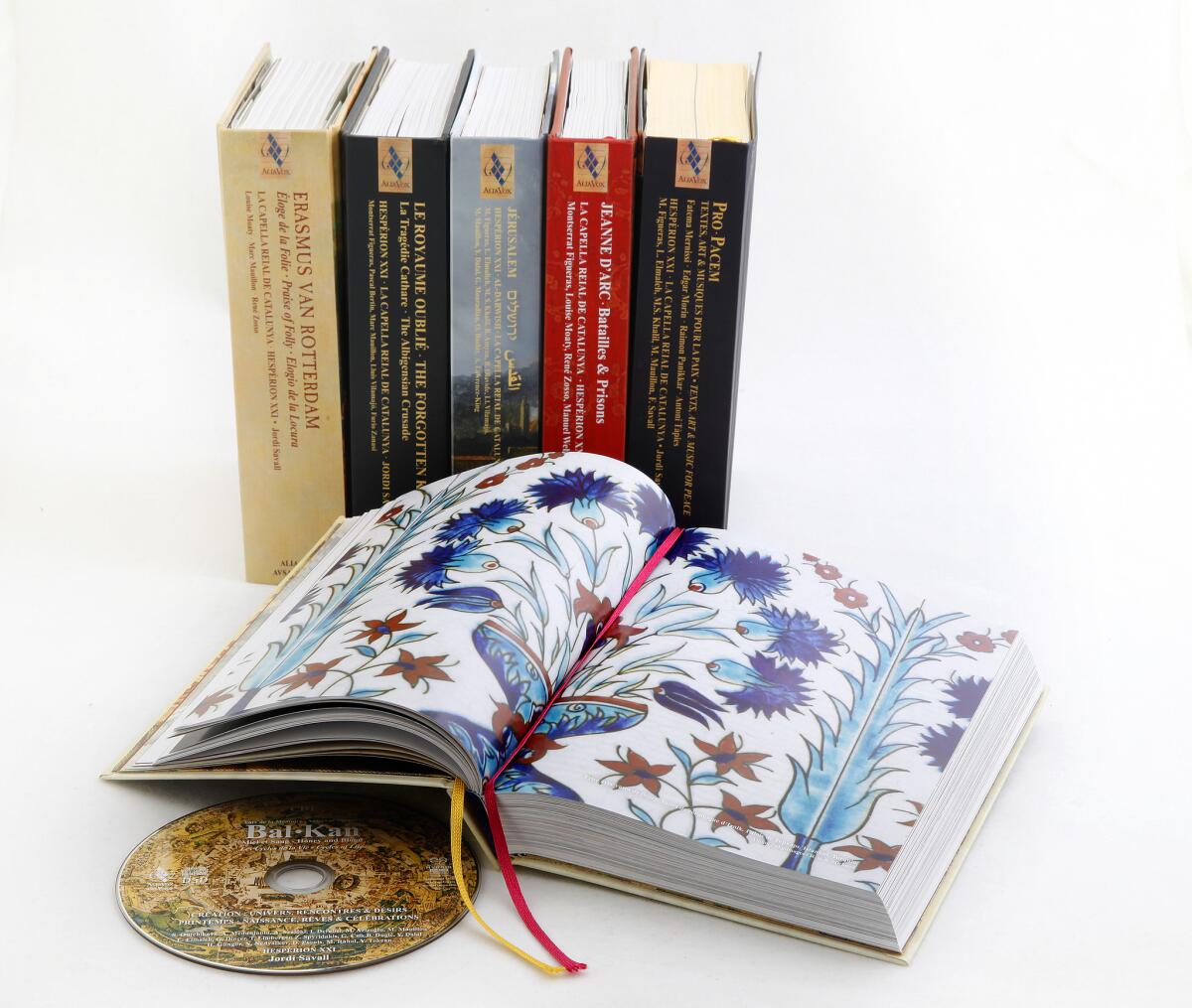

Along with recordings of a wide range of Renaissance, Baroque and early Classical repertory, he produces, around once a year, a grand recording project that comes in the form of a thick, lavishly illustrated book (with slots for several CDs) based on a figure (Joan of Arc, Erasmus), a place (Japan, Jerusalem, Syria), historical subject matter (the Crusades) or a plea (peace).

The plea for peace is in fact the subtext for all the above. Savall, in all his projects, searches for what connects cultures though time and space.

His latest grand effort, coming out March 11, is “Bal-Kan: Honey and Blood.” Although almost modest compared with Savall’s nearly 1,200-page “Pro Pacem” or “Erasmus: Praise of Folly” with six CDs, the book, “Voices of Memory,” is a beautiful 600-page tome with chapters in a dozen languages. The accompanying three gorgeously recorded super audio CDs feature 40 folk and classical Bulgarian, Macedonian, Hungarian, Serbian, Romanian, Greek, Bosnian, Cyprian, Turk, Armenian, Moroccan and Sephardic singers and instrumentalists trying to see how music might reveal not just the spirit of the Balkan soul, a fine enough project, but the broader meaning of modern life.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The Balkan region, Savall writes in his introduction, has “always been a highly contentious cross-roads, constituting at one and the same time a rich meeting point and the theater of dramatic confrontations.” Balkanization, the project is also meant to remind us, has become a term to designate the political fragmentation and violent divisions commonplace right now on the planet.

We cannot, of course, blame the Balkans for the revolts in Ukraine, Venezuela and Syria at the moment, but “Bal-Kan” does remind us that this year marks the 100th anniversary of the start of modern conflagration. World War I erupted June 28, 1914, when Austrian Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo.

Savall, however, further sets out to remind us that this “powder keg” of a territory also happens to be the cradle of European civilization. Much of how the world sees itself today grew out of the interactions of Christian, Jewish and Arab cultures in the region in a process far more individual than the commercial globalization found on modern mass media or increasingly homogenized “world music.”

Bal and kan were the Ottoman terms for honey and blood. Savall contrasts that sense of extremes with the “Cycles of Life” — creation, the seasons and “(re)conciliation” — an idea he got from his wife, soprano Montserrat Figueras, shortly before she died in 2011.

PHOTOS: Disney Hall conductors

The first number is an improvisation for Hungarian cimbalom, Croatian lute and double bass in an intensely flavorful gypsy style. Put this out as a single, market it right, and you could have a surprise hit.

A couple of hours later, an Israeli singer, Lior Elmaleh, begins the final grouping with a song in praise of the Torah. A beautiful, prayerful folk tune is caringly accompanied with viol, organ and double bass. It is followed by a Greek song, a Turkish song, a Serbian song, a Sephardic one (taken from a 2005 recording made by Figueras) and another captivating gypsy improvisation. Finally, a wide range of instrumentalists and singers returns to the Torah tune as an up-tempo celebration suitable for a wedding.

Savall offers no explanations of the actual pieces other than where they come from. You are on your own to find out about the oud, kaval, ney, brac, duduk, rebab, gadulka, santur, tupan, kemence, tambura, tanbur, kanun, Greek lyre and barrage of percussion that he combines in rarely predictable ways with period instruments and modern European ones.

None of the 53 individual numbers resembles another. Some honor traditional styles. But then you might find an improvisation from Greek and Albanian sources featuring Bosnian and Turkish soloists on clarinet, ney, kanun, oud and percussion for a kind of all-Balkan jazz session. What is gripping is not the similarity, not the blending, but the brilliant emphasis on individuality. Each instrument is something fresh; the newness catches you continually off guard.

GRAPHIC: Highest-earning art executives | Highest-earning conductors

Differences, be they musical or cultural or religious, do matter. We go from one number to another and another, passing through the times of life, getting all kinds of advice. A 14th century Hungarian ballad — accompanied by Savall and Turkish, Sephardic and Greek players — offers young girls warnings: “A bad man is like mourning to you.”

Ultimately, the different sounds go together not because they belong together but because they don’t belong together. We are given space to co-exist, and our ears perk up. We begin to feel proud of ourselves as listeners by being able to recognize more than one kind of music at a time. That leads to recognizing more than one attitude at a time. Flip through the book and the photos of the players are characters in a travelogue. The sterling reproductions of Balkanartwork are more tales newly told.

Music cannot by itself change the world. A bad man will always be like mourning. But as June 28 approaches, expect to hear a lot about the way war did change the world, and all that led up to it. Musical life in Europe, and especially in Vienna and somewhat in Paris, graphed the roiling psychic profile of an age in turmoil. Listen to Strauss and Schoenberg and Mahler and Stravinsky and you can get a pretty good idea of where Europe was headed.

Savall, on the other hand, steps back, way back, for a more encompassing perspective. The Balkans are not one people, one religion, one culture, one place or participants in one history. The region’s diverse populations have gotten along and by doing so enriched civilization. They’ve warred and by doing so enticed some of civilization’s worst devastation. The cycle, like the cycles of life, will no doubt continue.

But by mingling richly multi-Balkan music sweeter than honey with tones and drones thicker than blood, Savall’s becomes the voice of memory as we now need it.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.