Review: Radar L.A.’s ‘Stones,’ ‘Dogugaeshi’ an illuminating contrast

A wrathful, wondrous, clairvoyant, powerfully sexual and just as powerfully beyond-sex Maori women’s dance ritual had its astonishing first public presentation Thursday night as part of Radar L.A.

Whimsical Japanese puppetry followed a half-hour later.

Lemi Ponifasio’s “Stones in Her Mouth,” the Samoan choreographer’s new work for his company MAU, was not intended to be a double bill with “Dogugaeshi,” created by American puppeteer Basil Twist and Japanese musician Yumiko Tanaka a decade ago. The shows had little to do with each other, geographically, theatrically or psychically.

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview

But it was possible, with a little hustling from the Palace Theatre on Broadway to REDCAT at 2nd Street, to see both, and the contrast was illuminating.

I cannot explain “Stones in Her Mouth,” which will have its official premiere in Bruges, Belgium, at the end of the year and is being called at the Palace an “avant premiere.” Ponifasio doesn’t offer much help in the short program note. The work is described as “women saying what they want to say to the world right now.” They “rage against the apparatus of power, oppression and even Western-style feminism.” They rage, but they also rise, defining themselves “through a mythological authority.”

What they say is in the form of Maori songs and chant and Ponifasio’s extraordinary ceremonial movement language. Texts are provided but not translations. To different audiences “Stones” may have different meanings. But the real meaning is in the movement, the voices and the unforgettable presence of 10 women.

They appear gradually and not in a welcome manner. We hear distant chanting while staring at, or trying to avoid, a square of light on the stage that hurts the eyes. It goes away after about 10 minutes, but an equally bright line of what appears to be LED lights at the foot of the stage never does throughout the 90-minute performance (and only rarely dims in intensity).

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

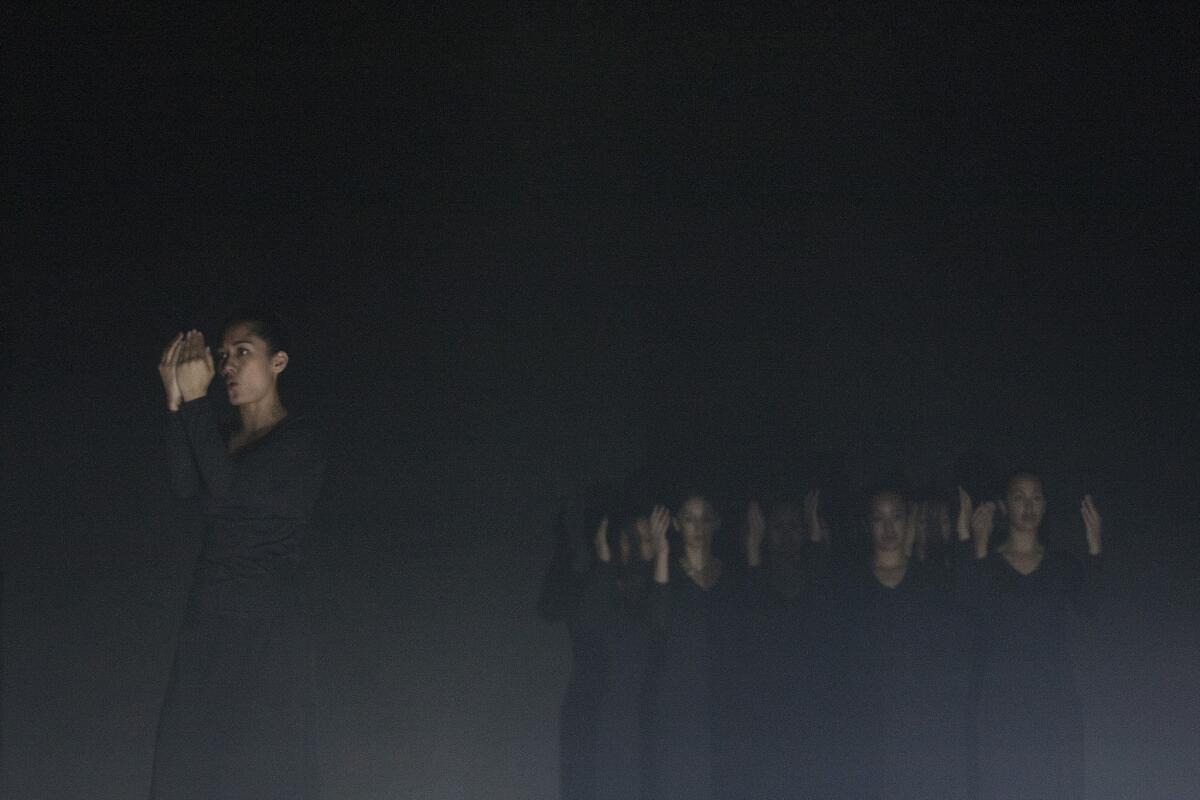

One woman, chanting, appears as if indistinctly lighted in a heavy fog. Then another. Eventually there are five women dressed in long, tight black gowns (there will eventually be 10). Their lips are painted penetrating red. An electronic drone accompanies them.

The five women move only their arms at first. Gestures are slow and languorous but become increasingly emphatic. They are synchronized and in mesmerizing command of attention.

One kind of movement and/or song and/or shriek follows another in different formations. Early on a row of women cover their faces with their hands, as if they are wearing masks. At one point a tall nude with strategic body paint slowly walks onto a bare stage and lies down in sacrificial stillness. A dancer in black, ritualistically twisting a spear, threatens but doesn’t attack.

There are elements in Ponifasio’s work that seem to allude to Pina Bausch (in the utter self-possession of the women), to Merce Cunningham (in the magical expressivity of abstract dance) and to Robert Wilson (in the use of light, posture, stage presence and ineffably meaningful movement). Certainly a chorus line twirling light bulbs on a string in “Stones” — a gorgeous sight to behold — had a Wilsonian look. So, too, did the makeup.

But the soul of “Stones” is not that of an American or European sensibility. Instead, Ponifasio uses these sophisticated Western theatrical and choreographic techniques to reveal an essence of femininity that we may not, on our shores understand and are not asked to understand, but rather to enter. The 10 dancers are exceptional. “Stones” is a brilliant, deep work.

If Ponifasio strips away artifice to reveal essences, Twist does almost the opposite. An entertaining celebration of artifice, dogugaeshi is a 17th-century form of Japanese puppetry that is as much about inventive use of the screens as it is about puppets.

PHOTOS: Best in theater for 2012

And it is those screens that capture Twist’s imagination. He introduces a few irresistible cat-like creatures in his “Dogugaeshi,” but he makes the screens serve to mess with the audience’s perception. There is one behind another behind another behind another, and eventually you lose complete sense of proportion. When Tanaka appears next to the puppets, playing the shamisen (a three-stringed ancient lute) or koto, she looks like a giant.

Japanese court music and culture is occasionally invaded by pop culture (Broadway and Tokyo). A puppet village rises and falls. Modern techniques, including projection, are combined with traditional Japanese and non-traditional American puppetry.

The hour-long performance progresses cleverly like a collage. By the end it no longer surprises and the material begins to feel a little thin, but enchantment lasts until the final screen closes.

“Dogugaeshi” is a diversion. Twist brings us back to reality with gentlemanly gentleness. Ponifasio throws “Stones” at us. His disquieting women mean momentous, lasting business.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.