L.A. Opera’s unlikely — and unusual — ‘The Magic Flute’

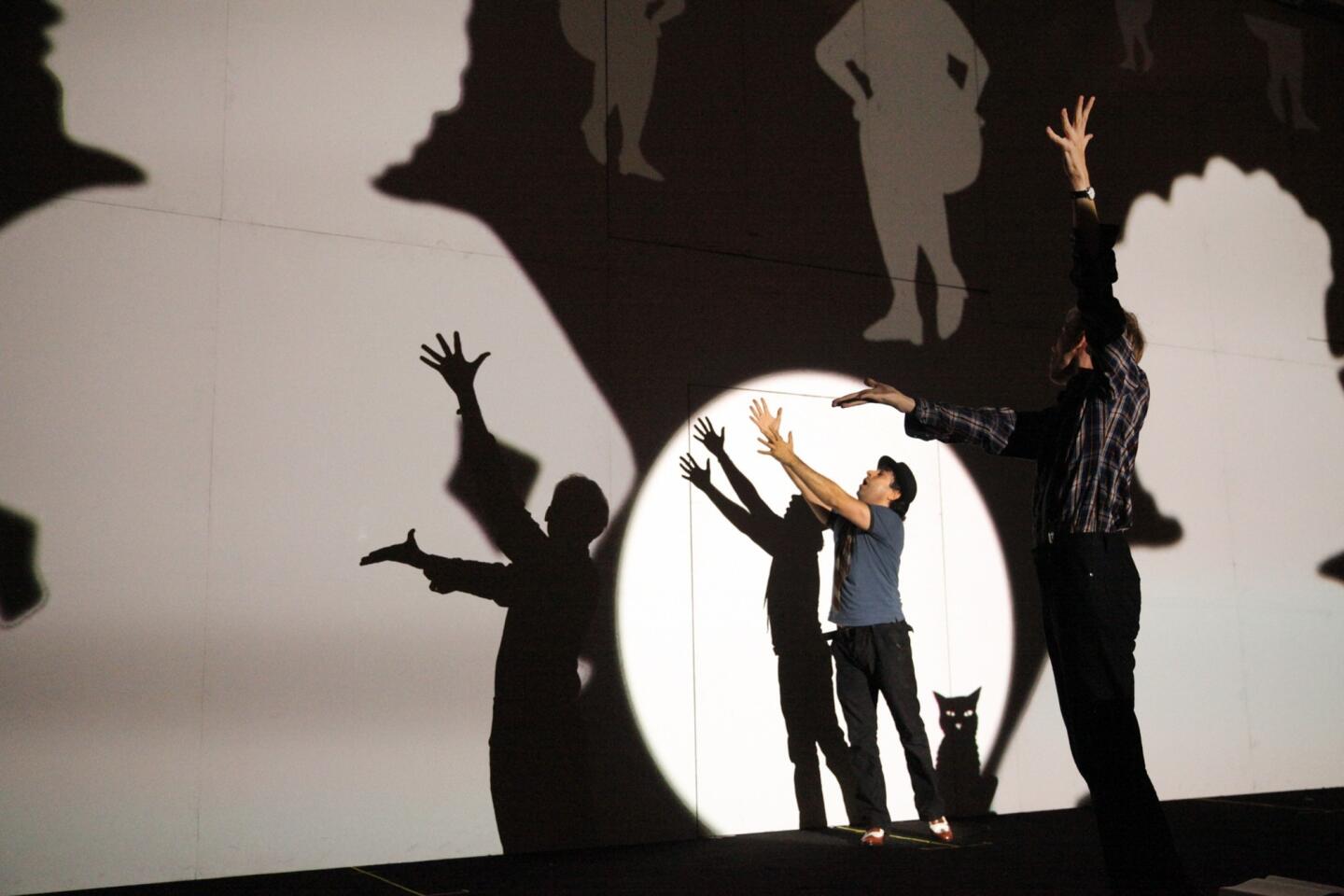

In a bare rehearsal space downtown at the Music Center, a dozen or so people work through a scene in the dark. The only light comes from projected black-and-white animation flickering on the back wall of the stage — a nude fairy fluttering her wings atop a tree, a black cat leaping over a glowing full moon.

Rodell Rosel, who plays the lovesick Monostatos in this Los Angeles Opera production of “The Magic Flute,” gestures wildly from a vine-covered balcony; he is crooning his affection for Pamina (Janai Brugger), whose heart belongs to someone else. Rosel ominously wriggles a black-gloved hand in her direction on the other side of the balcony.

Suddenly, a swarm of animated, disembodied black gloves appears on the wall, wriggling their fingers too, inching closer to Pamina’s neck. She retreats, her back against the wall. The live piano accompaniment races — rapid-fire Mozart — at first whimsical, then increasingly intense.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

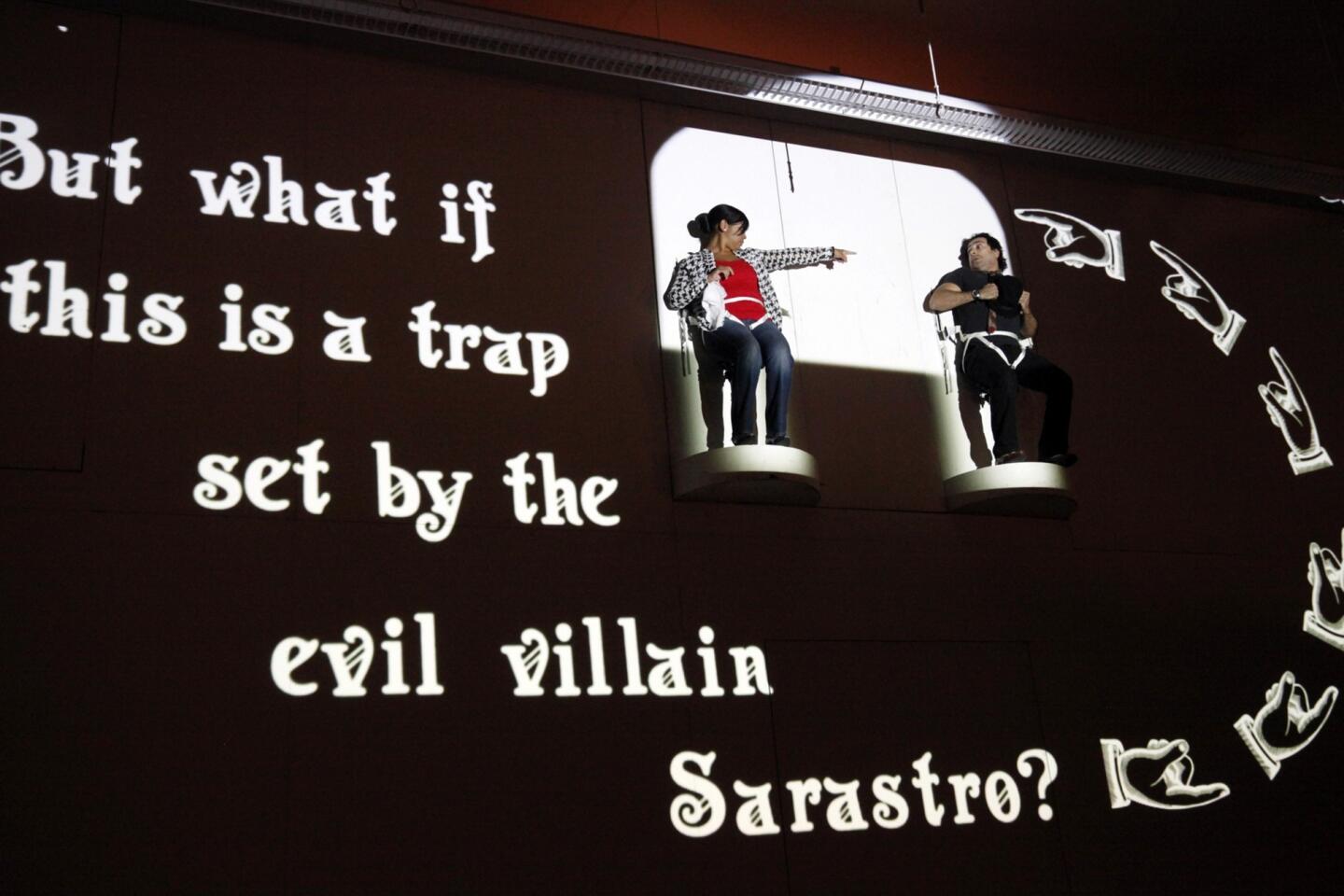

Until: “Kill Sarastro!” appears scrawled across the wall, punctuated by the sound of a few deep, angry chords.

The scene is at once lighthearted and creepy — decidedly not the beloved and familiar Peter Hall-directed and Gerald Scarfe-designed production of “Magic Flute” that over the last 27 years graced L.A. Opera’s stage on four occasions.

This “Flute” — which receives its U.S. premiere at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on Nov. 23 — is an interactive, nontraditional reinvention that combines live performance and hand-drawn animation; it weaves throughout visual references to silent films of the 1920s and 1930s, specifically the comedy of Buster Keaton and the kitschy horror of the 1922 German Expressionist film “Nosferatu.” And its creative force is unlikely, a man who once blanched at the idea of this opera.

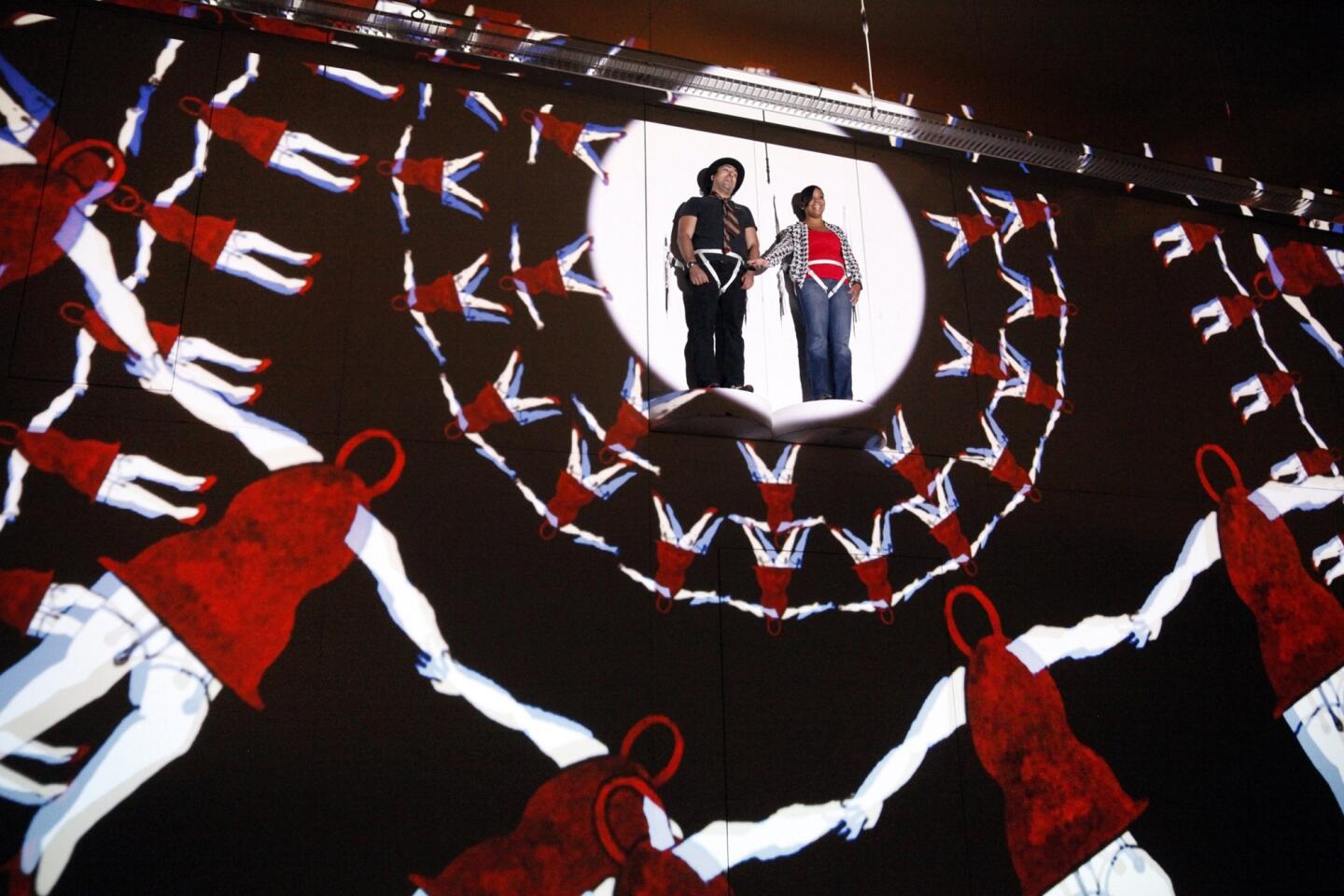

Mozart’s two-act opera, written in 1791, is a mystical story about the power of love and Tamino (Lawrence Brownlee), a prince seeking spiritual enlightenment. The production, which also features Rodion Pogossov as the bird-catcher Papageno, is a collaboration between Australian opera director Barrie Kosky, the artistic head of the Komische Oper Berlin; and the British avant-garde theater company 1927 led by Suzanne Andrade and Paul Barritt.

This multimedia-infused “Magic Flute” debuted in 2012 to much fanfare at the Komische — an experimental house in opera-saturated Berlin. Andrade and Kosky co-directed the production in Berlin, as they will in L.A. — it is Kosky’s U.S. directing debut — and Barritt drew the animation, which took about 18 months to sketch by hand. L.A. Opera music director James Conlon will conduct.

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview

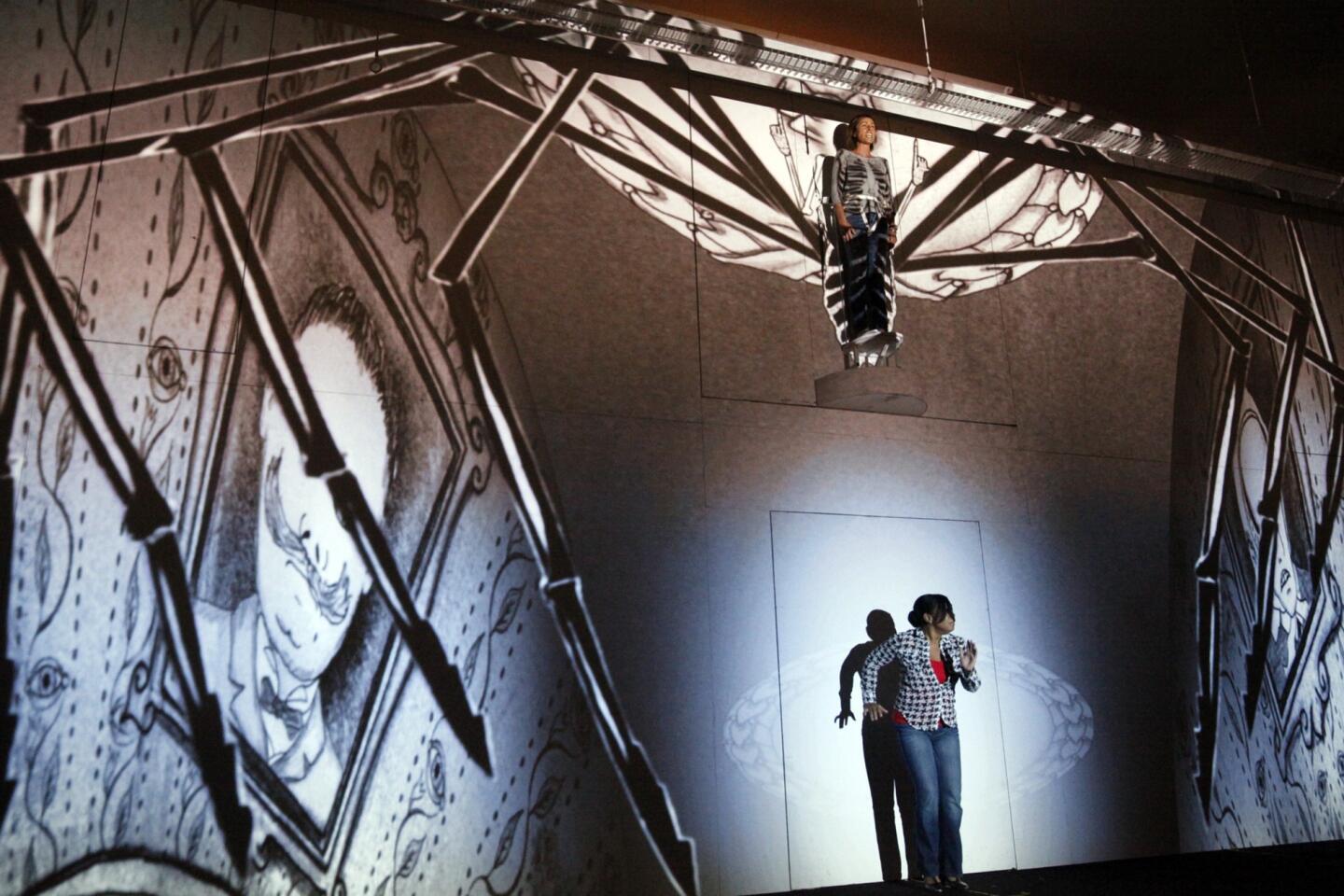

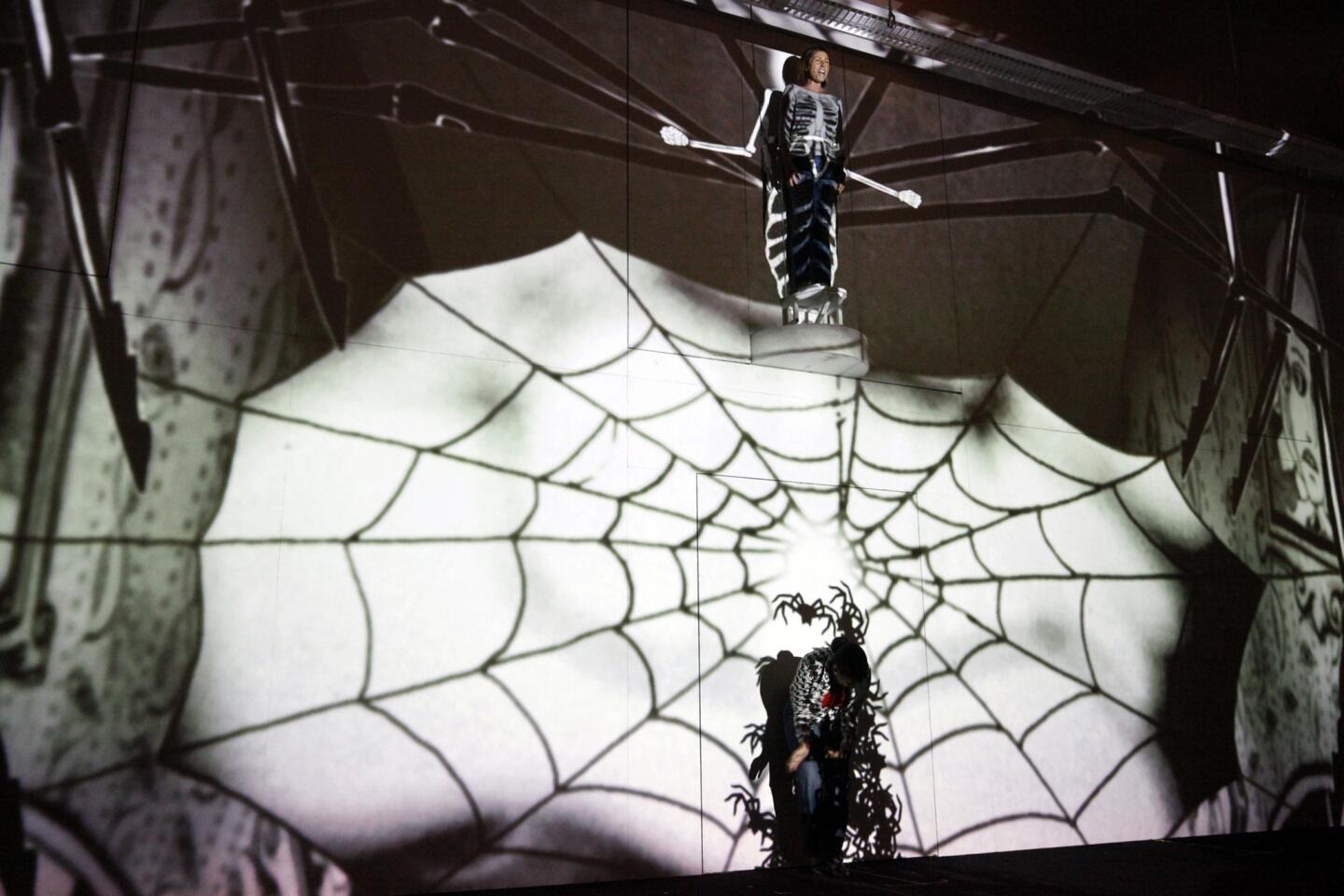

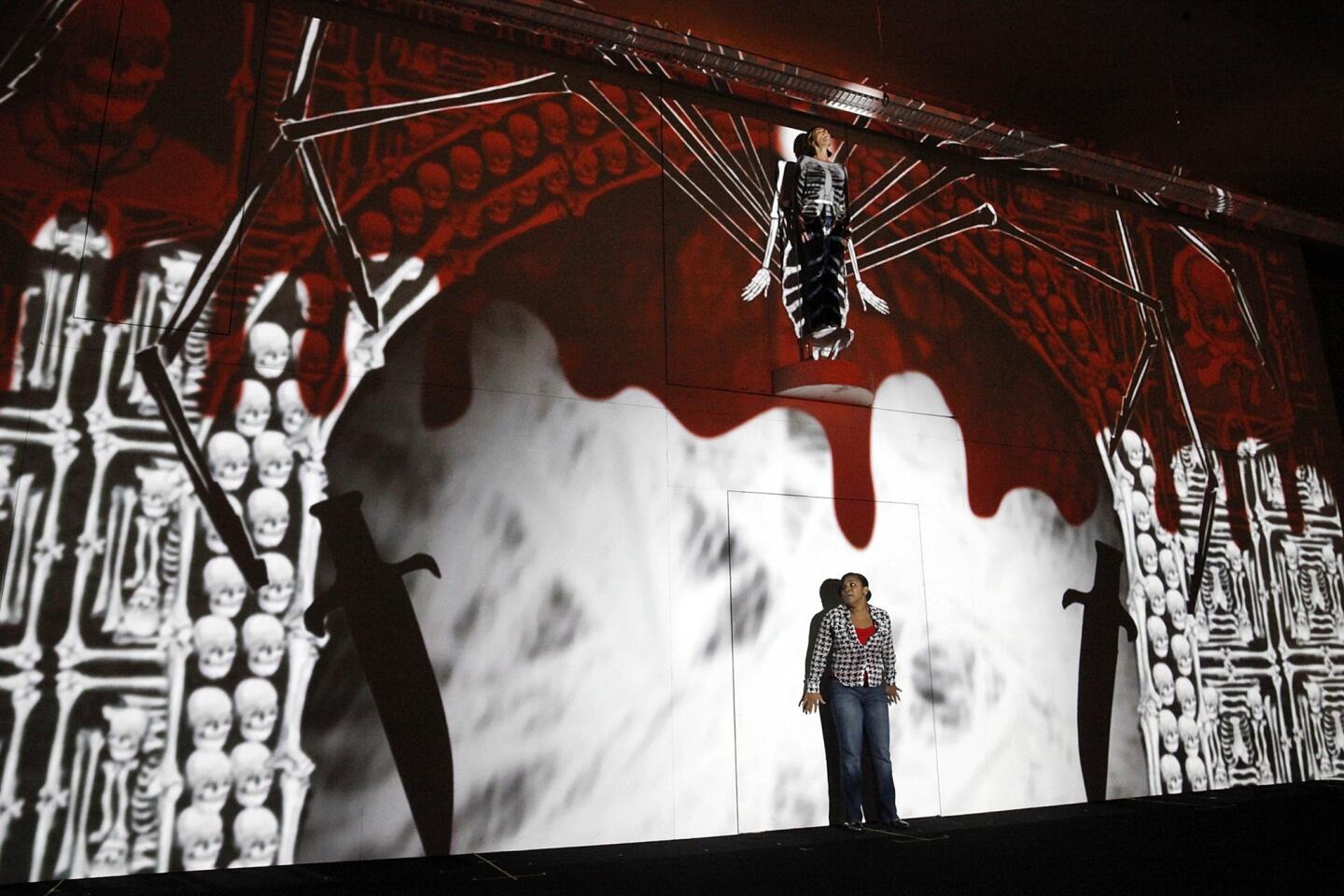

“What the audience sees is a very large screen and sometimes the performers are stuck, like insects, to it or on the floor, and the world around them is animated,” Kosky says on a June visit to Los Angeles for preproduction meetings. “The three-dimensional performer is sort of playing with the animation in this low tech but quite beautiful way.”

Kosky, in his 1960s East German bowling shoes, chunky silver rings and designer eyeglasses, settles into a folding chair in the L.A. Opera’s costume shop. The space is crammed with colorful outfits from operas past, here a gypsy armor from “Il Trovatore,” there a Spanish bullfighter’s uniform from “Carmen.”

Kosky, who joined the Komishe for the 2012-13 season, is the youngest and first non-German to head it. Part of the appeal in reimagining “The Magic Flute,” he says, was pushing, even further, the company’s tradition of innovation. Berlin has three major opera houses, including the Komishe, and he wanted the 66-year-old company to stand out.

“There’s so much opera going on in Germany, they’ve seen these operas so many times,” Kosky says. “The audience demands something different, particularly in Berlin. ‘Show us something new, we want to be delighted!’ ”

Interestingly, Kosky never had any desire to put on “The Magic Flute” — he even actively avoided the Mozart fairy tale, he says, turning down multiple offers to helm the production throughout more than 25 years directing opera.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

“I saw it first when I was 8 and hated it,” Kosky says.

“Of course the music is stupendous, but I didn’t know how to do it. The combination of the fantastical and psychological elements with this sort of pseudo religiosity — how do you make all that work in one piece?”

It wasn’t until Kosky caught Andrade and Barritt’s 1927 production of “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea” — a vignette-based piece with a slightly dark cabaret feel that incorporates bits of animation — in Hanover, Germany, in 2009, that his mind was opened.

“Their style was weird and wonderful, and I instantly thought maybe they’d be the right people to do ‘Magic Flute’ with,” Kosky says. “Suddenly, I’d found a way to do it.”

The resulting production is 1927’s opera debut — something the company’s team knew absolutely nothing about before meeting Kosky. “They’d never been to the opera — they didn’t even know what ‘The Magic Flute’ was,” Kosky says of Andrade and Barritt.

“It’s a bit of a new world for me,” admits the London-based Andrade, who had a background in performance poetry before co-founding 1927 and is in L.A. for “Magic Flute” rehearsals. “But we’ve played around with lots of humor and silliness, and that’s where our sensibilities have married very well. We looked at old cartoons, old animation, old comic books and thought of these quite classic gags. At the same time, we’ve been very faithful to the music and the text.”

GRAPHIC: Highest-earning conductors

Christopher Koelsch, L.A. Opera president and chief executive, was an early fan. When “The Magic Flute” debuted at the Komische in Berlin in late 2012, the L.A. Opera already had scheduled the familiar Hall-Scarfe production for this season. Then Koelsch saw a clip of the Kosky-1927 collaboration of “The Magic Flute” on YouTube and flew to Berlin to see a live performance.

In June, L.A. Opera announced it would be making a swap, staging the new “Magic Flute” that Koelsch had seen in Berlin instead. (A co-production with Minnesota Opera, it will debut in Minneapolis in April.)

“With its seamless, charming evocation of silent film tropes and the beloved legacies of Keaton, [Louise] Brooks and Chaplin, the Kosky-1927 production of ‘Magic Flute’ feels perfectly and indelibly idiomatic to the birthplace, and home, of cinema,” Koelsch says.

“Frankly, to have the production premiere in the U.S. anywhere other than Los Angeles would have been a mistake, which is why we were determined to act so quickly to bring it here.”

Kosky points out that the production is as endemic to Berlin, given that city’s filmic history. “Berlin is the history of American film,” he says, “because so many of the cinematographers, writers and composers in Hollywood in the ‘20s and ‘30s were emigres from Berlin.”

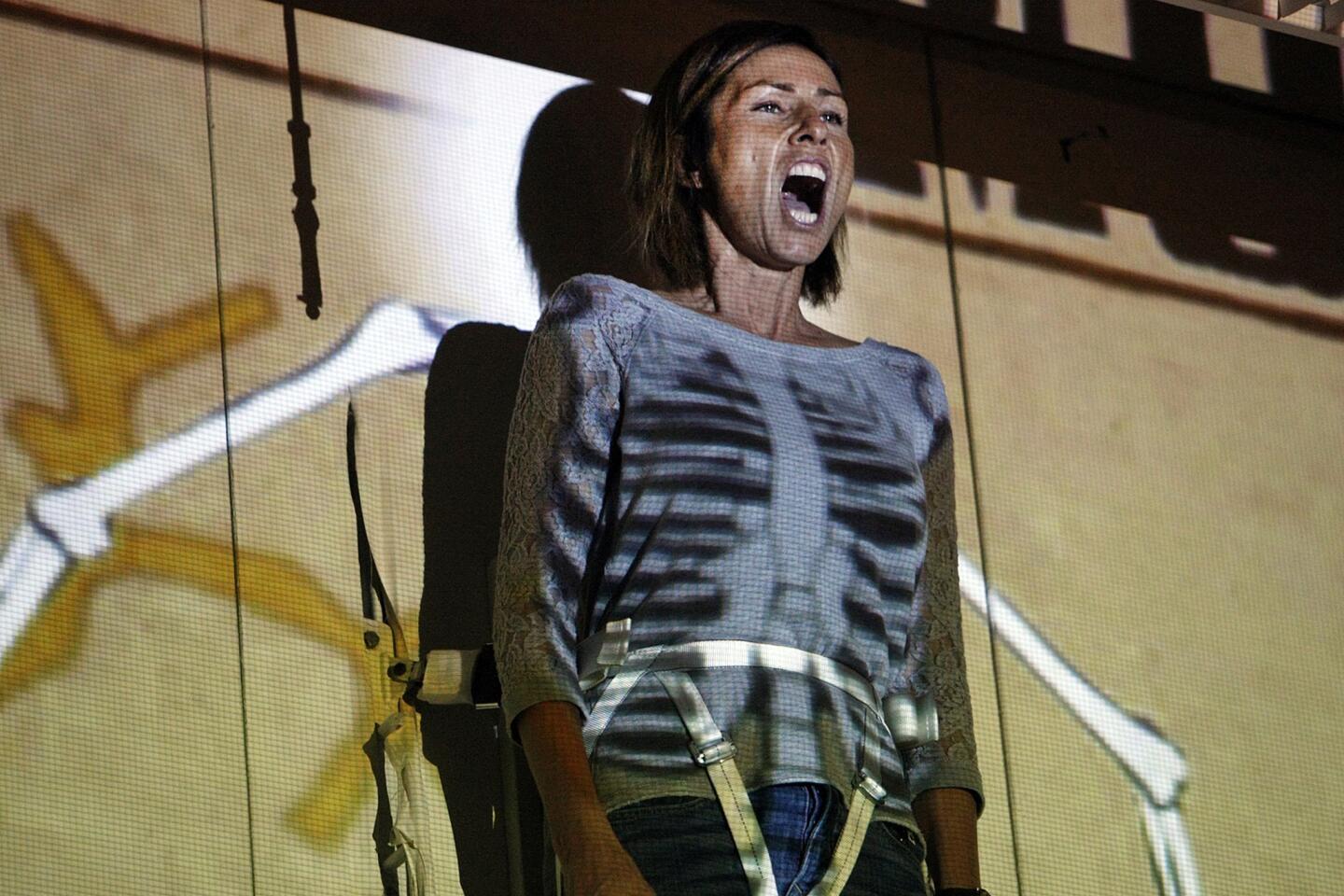

Instilling that cinematic sense in “The Magic Flute,” however, was not easy. The interplay between the live performers and the animation is so precise that the blocking and rehearsal process can be “nightmarish,” Kosky says. Performers often are strapped into harnesses or hanging from high perches, needing to hit exact marks so their actions are in sync with the animation — Pamina running from a pack of projected hunting dogs, for instance, held on a leash by Monostatos.

But Andrade, with the help of the Komische’s Tobias Ribitzki, the associate director, says the process during L.A. rehearsals is par for the course for 1927.

“It’s just how we stage shows,” Andrade says. “You’re constantly thinking about the blocking. The performers are integral to the animation; otherwise, you just have performers and video, which is what a lot of multimedia and video art ends up being.”

“It’s challenging but also exciting,” Brugger says about rehearsing the part of Pamina. “We have to learn to be expressive. With some of the restraints, like the harness and being up so high, we do more with our facial expressions and with big hand gestures.”

This sort of complex integration between traditional theatrical elements and edgy animation has broad appeal, Kosky says. He thinks part of the reason his reinvention of “Magic Flute” was successful during its Berlin run — the initial 13 performances sold out in two days — was because it worked on multiple levels, for children seeing it for the first time as well as grandparents sitting with them.

“There’s beauty and references that the kids never get at all, this quiet, quirky humor and moments of exquisite stillness,” Kosky says. “And the kids — they don’t know how it’s done, why people are floating.”

Kosky fidgets with one of his silver rings, a 19th century Prussian spoon hammered into a circle, around his finger. He’s seemingly almost nostalgic for the opera of his youth, the work he vowed never to put on — at least not in any expected way.

“I think what we’ve done is return the piece back to a lot of its original roots,” he says. “Because it was unlike any other of the Mozart operas when it was first written and performed … it was this weird mix of vaudeville and opera — and you have to celebrate that, the sort of mutant nature of the piece.”

----------------------------------

‘The Magic Flute’

Where: Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, downtown L.A.

When: 7:30 p.m. Nov. 23 and 30, Dec. 5 and 11; 8:30 p.m. Dec. 13; 2 p.m. Dec. 8 and 15

Tickets: $19 to $325

Information: (213)-972-8001 or https://www.laopera.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.