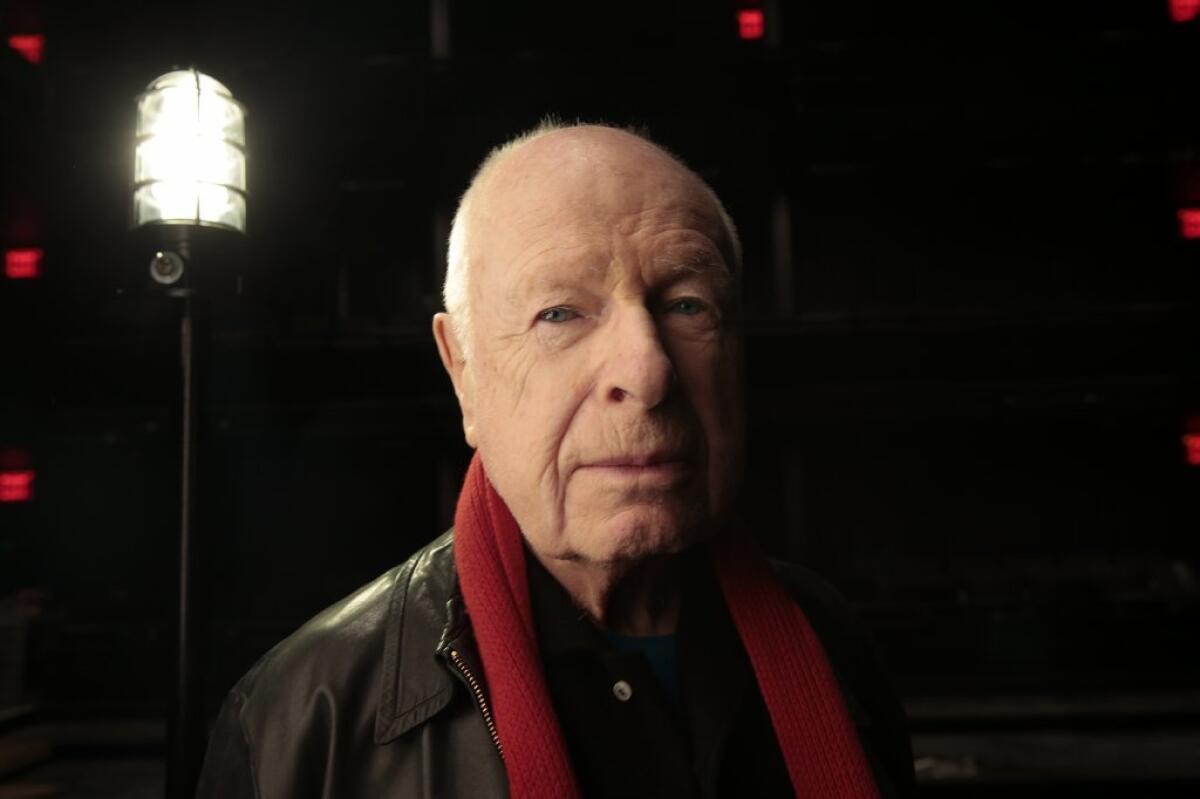

Peter Brook at 89 keeps slipping into new suits

Through nearly 70 years of acclaim as a theater, film and television director — most particularly as a theater director — Peter Brook has been called a magician many times.

In 1962, the British critic Kenneth Tynan extolled him not for pulling a rabbit out of his hat but for an unprecedented approach to “King Lear” that for the first time made the character a palpably human, “edgy, capricious old man” instead of “the booming, righteously indignant titan of old.”

Brook, who recently celebrated his 89th birthday, clearly absorbed a fundamental lesson of “King Lear”: considering its pitfalls, perhaps retirement is best put off as long as possible.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

So the work continues for the Englishman, who’s made Paris his creative base since the early 1970s. New Brook is afoot with the current U.S. tour of “The Suit,” which he and his longtime collaborator Marie-Hélène Estienne have adapted along with musician-composer Franck Krawczyk from Can Themba’s 1950s short story about a marital disaster in a black South African township. It comes to UCLA’s Freud Playhouse, Wednesday through April 19.

Newer Brook is on the way with the premiere later this month of “The Valley of Astonishment” at his home venue, Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord. It’s the third in a series of plays about the human brain that Brook and Estienne have developed over more than 20 years.

“Our work has been built from the very start on nothing being fixed and everything being reworked and rediscovered and, one hopes, growing,” Brook said in a telephone interview.

In an era when rock bands ritualistically recycle their classic albums note for note in concert, Brook moves forward with no thought of reviving his signature past productions, which include Peter Weiss’ “Marat/Sade” in the ‘60s, a landmark 1970s staging of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” with Puck flying on a trapeze, and a nine-hour, 1980s journey through the Hindu epic “The Mahabarata.”

Brook also made his mark in the movies, directing the 1963 film of William Golding’s novel “Lord of the Flies.”

PHOTOS: Faces to watch 2014 | Art

He became a certified sage of the stage in 1968 with his first book, “The Empty Space,” advocating an approach to theater that aspired to organized spontaneity at every moment of rehearsal and performance (an approach his son, Simon, focused on in a new film documentary, “Peter Brook: The Tightrope,” which shows the director working with young actors).

“I always go by hunches,” Brook said in the interview, and it’s because of how the hunches fell that he waited 10 years to create an English-language version of “The Suit,” which he’d toured in French from 1999 to 2002 as “Le Costume.”

The original plan, Brook said, had been to move immediately from French performances to a second round of touring in English. Performances were booked but had to be canceled.

“I can’t analyze why, but we realized, ‘This isn’t the moment.’ It wasn’t coming together. We left it, and nearly 10 years went by until Marie-Hélène came back with a very strong feeling that we should pick it up again.”

By that time, Krawczyk had entered the picture as the sole accompanist for Brook’s stripped-down staging of Mozart’s opera “The Magic Flute,” which premiered in 2010. While that show was in Amsterdam, Brook said, Estienne took a walk through the city and “heard someone in the distance singing a serenade of Schubert.” The moment helped shape the transformation of “Le Costume” into “The Suit.”

ART: Can you guess the high price?

The French version had used recorded music; now there’s a live instrumental trio to accompany the four actors. The music illuminating the characters’ hopes and feelings has been broadened to include Schubert and the Billie Holiday ballad “Strange Fruit,” as well as African songs. The staging remains simple, with metal clothes racks the central design feature.

Themba’s story portrays an ambitious young man who, told that his wife is having an affair, rushes home and bursts in on a tryst. The paramour flees, leaving his suit draped on a chair. The husband icily imposes a humiliating penance: the couple will treat the suit as if it were a living person — their honored house guest.

Themba was a fiction writer and journalist during an early 1950s cultural flowering in Sophiatown, a ramshackle but vibrant black district near Johannesburg — until South Africa’s white regime shut it down. His short story did not allude directly to the racist system obstructing his characters’ lives (it hardly needed to for his original readers), but Brook makes the connection explicit by having a narrator announce, “the story I’m going to tell couldn’t have happened anywhere except in countries like South Africa, which lived under the iron fist of oppression.”

“This is one of the few lines of the play I wrote,” Brook said, and he insists it’s true.

When it comes to stories of marital infidelity and its consequences, Brook said, “I’m absolutely convinced that out of all the millions of versions, nobody else has ever conceived it taking this form.”

For Brook, Themba’s life story amplifies the play’s theme of racism distorting and thwarting its victims’ lives. “There was a total embargo on a black man writing a novel — can you imagine that? He had talents that could have made him into a Chekhov, but in about 10 years he was dead. He’d left South Africa and died of drink” while still in his 40s.

Brook sees economic forces as the worst cause of creative distortion for today’s theater artists, especially emerging writers and directors, who he thinks are being denied the subtler material and approaches that were welcome when he was starting out in the mid-1940s.

“When it’s linked to high prices, a play has to be a hit,” he said. “You have to feel you’re hitting it on the nose right away and making this impact. It leads to a brutality, a crudeness, even a violence, or a use of sex as pornography. Today you have to bash in with a lot of violence and a lot of noise.

“That’s so much the movement of our time” in many facets of life, he added. “I make a habit now of finding in every city a quiet restaurant. It’s harder and harder, because people want to enter that steam bath of shouting. One has to work against it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.