In Havana, following a USC museum director in search of great Cuban art

- Share via

The Caribbean waves lap up against a decaying concrete wall outside artist Cirenaica Moreira’s home studio in the fishing village of Cojimar. The house is perched on a sun-bathed inlet that flows into a nearby harbor. Ernest Hemingway once docked his boat within eyeshot of the artist’s now-crumbling back patio. A faded, multicolored pinwheel spins in the wind, and Cuban pop blasts from a nearby boat.

Inside, about 18 travelers from Los Angeles and New York gather in Moreira’s bedroom, a bright and tidy space with stacks of books on the floor, dried flowers in lace-wrapped vases and vintage-looking postcards tacked to the wall. Standing by her bed, Moreira gingerly holds up one large black-and-white photograph after another.

One is a nude self-portrait, the artist draped in the Cuban flag, from her series “Eyes That Saw You Leave.” It was created in the early ’90s, after the fall of communism, when scores of Cubans left the country because of dire economic conditions. Another photograph from that period, when art supplies were scarce and artists relied on the creative repurposing of everyday objects, depicts Moreira wearing a bow in her hair crafted from bent spoons and a prosthetic baby bump made from tin soda cracker cans. It’s called “Best Consumed No Later Than 30 Years After Opening.”

Selma Holo, director of the USC Fisher Museum of Art, stands nearby, nodding enthusiastically as Moreira turns over each photograph. “They’re beautiful — so poetic,” Holo says.

All of a sudden, we feel we can go there, make studio visits, see the artists and understand where they’re coming from.

— Selma Holo

Holo has made the pilgrimage to Cuba for a tour of artists’ studios. with L.A.’s Couturier Gallery, which specializes in Cuban artists. As U.S.-Cuban relations continue to improve, and travel to the island becomes easier, art world fascination with the region is mounting. Collectors, museum and gallery directors, artists and tourists are flocking to the area. Cross-cultural collaboration is all the rage.

This month alone, shortly after President Obama’s visit to Cuba in March, several Cuban-specific art exhibitions opened in Los Angeles. CalArts’ Center for New Performance organized “El Acercamiento/The Approach,” a multimedia exhibition featuring student and professional artists from the U.S. and Cuba. It opened in Havana in March and in Los Angeles on May 7, and it will show in Miami this fall. Lois Lambert Gallery in Santa Monica premiered “Straight From Cuba: A Woman’s Perspective,” featuring five Cuban artists, on May 14.

“I think it really is the moment of awakening and awareness and possibility,” Holo says. “All of a sudden, we feel we can go there, make studio visits, see the artists and understand where they’re coming from. It’s the reality of contact that allows a curator to be excited about collecting — and that’s what’s happening now: We can go.”

Holo is with her husband, son and daughter-in-law on a weeklong tour with L.A.'s Couturier Gallery, which specializes in Cuban artists. She has a small budget for museum acquisitions, which, as of Day 2 of the trip, she says she may or may not dip into. Though the museum has a robust collection of more than 200 objects of Latin American art, it doesn’t own any works by Cuban artists — something Holo is hoping to rectify should the right works materialize.

When Moreira presents “Paris, 13th of July, 1793 (Death of Marat)” to the group, however — depicting a cast of the artist’s leg resting on pillows — Holo connects immediately.

“I bought it instinctively because I thought it was just very beautiful,” Holo says later that afternoon. “But then you start peeling away the layers, and it’s very deep. It refers to history. It refers to contemporary art and the use of the body. It’s almost surrealistic. It belongs in a university museum.”

Over the course of the trip, Holo visits 11 art spaces, an itinerary that includes some of the country’s leading artists, almost all of whom have shown in international biennials or whose work is on display at Cuba’s national museum, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. She stops at Fabrica de Arte, one of Cuba’s earliest (and the only privately run) multidisciplinary artist spaces and a hotbed for emerging talent. She also stops at the ArtSpace studio of Alex Hernandez, Frank Mujica and Adrián Fernández, as well as the family home of the late, pioneering printmaker Belkis Ayón, whose first retrospective outside of Cuba will come to the Fowler Museum at UCLA in October.

Winding her way through the artists' walk-up apartments, Art Deco homes, '40s-era casitas, midcentury modern studios and DIY galleries, Holo says she found much of the work to be particularly complex, both rooted in where it comes from and also universal.

"As isolated as Cuba has been," she says, "somehow or another, it's in the world art conversation in a way that is very engaged."

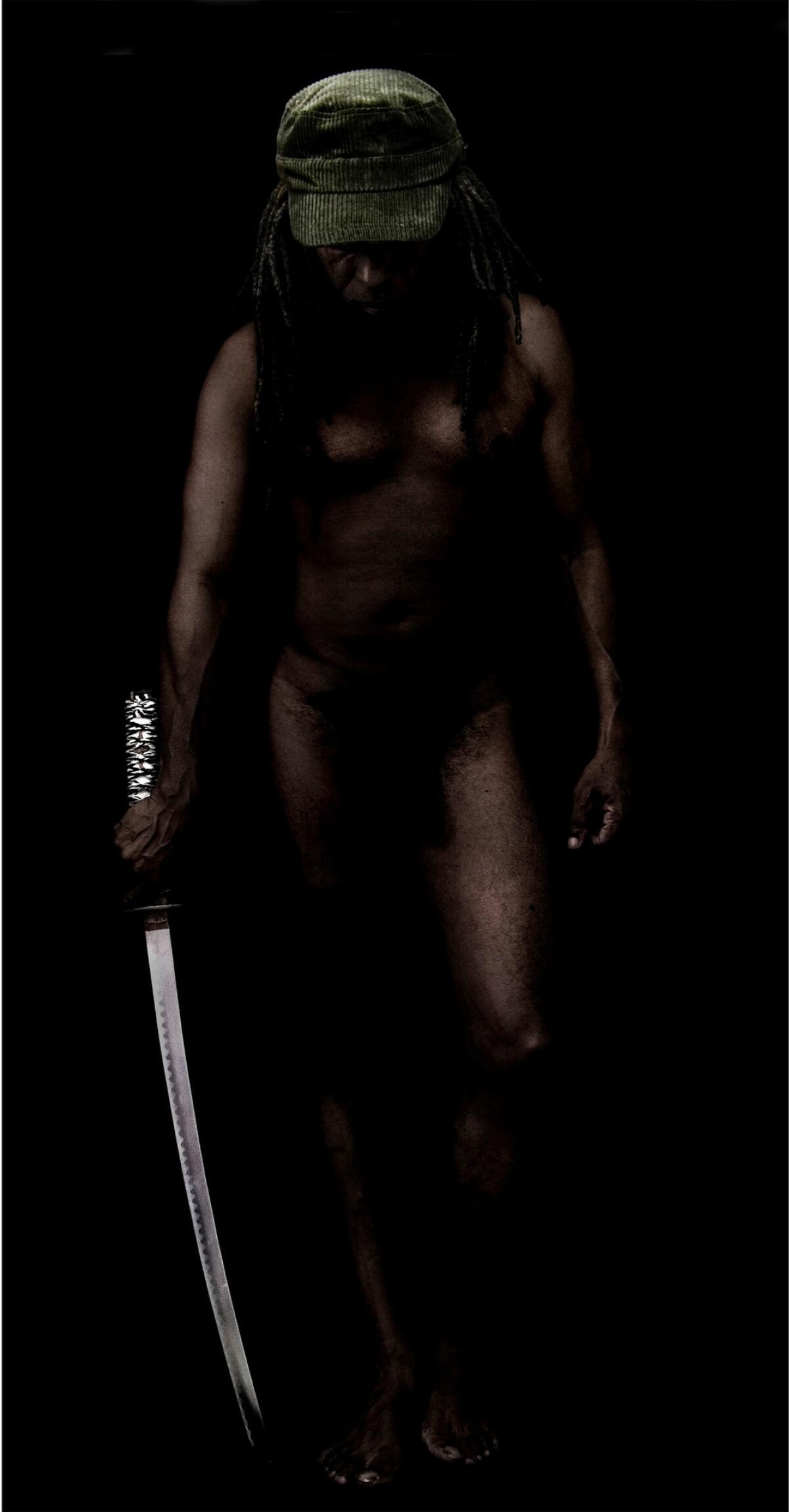

The second Fisher Museum purchase is from photographer René Peña, whose work deals explicitly with race, sexuality and identity. Peña’s “Samurai (after Donatello)” depicts the artist, nude but for a green corduroy cap, clutching a glinting metal sword. “It’s gender fluid and sexually ambiguous,” says Holo, who’s now envisioning a pop-up exhibition at USC later this year, to display the new acquisitions.

In the end, Holo acquires seven pieces by five artists for the museum, including works by Mujica, conceptual artist José M. Fors and experimental portraitist Eduardo Leyva.

So much of the art seen on the trip, she says, is about memory.

Scarcity of materials is the memory in sculptor and printmaker Abel Barroso’s crude hand-cranked smartphones made of wood, part of his Mango tech products series.

The memory of yesterday’s seemingly pedestrian moments — a lone tree or construction crane — drive Mujica’s dated, stamped visual diaries, meticulously detailed graphite drawings that look like old photographs.

Ephemeral paper memories are preserved in Fors’ installation of bundled letters and photographs, bound with string.

Artist Enrique Rottenberg at Fabrica de Arte recalls positive memories of artistic encouragement by, counterintuitively, a controlling communist government. Even in the most isolated of times, Cuban artists enjoyed privileges others didn’t, he says. Artists were seen as cultural ambassadors of sorts and therefore allowed to travel more freely and exhibit their work abroad.

“Artists always have had good living in this country,” Rottenberg says.

These works may be rooted in memory, gallerist Darrel Couturier says — just as all artworks are reflections of their surroundings. But many of them also are pointedly about moving forward and joining a global conversation.

“It is about memory, about recollection. We’re all an accumulation of fragments of memory. But this accumulation is about what informs our next step,” Couturier says. “The art we saw is more about universal things, wanting to connect and being part of the world.”

Perhaps Moreira, in her soft-spoken voice, puts it best while reflecting on the Fisher Museum’s acquisition of her work.

Standing by her open bedroom windows as wind chimes ping in the background, she says, “It’s just great to know that it’s important to other people in the world what I do.”

ALSO:

Unlocking Cuba: Travel tips, guides, photos and more

A dance music festival comes to Cuba and magic ensues

From ancient Persian poetry rises 'Feathers of Fire,' billed as largest shadow-theater play

The late Cuban artist Belkis Ayón's mysterious world unfurls at the Fowler Museum

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.