He’s in his 20s. She’s in her 70s. Together, they leave their mark in L.A. street art

At 9 p.m. two pairs of hands shimmied up a ladder to a rooftop on Highland Avenue at Melrose Boulevard. One set belonged to a young man, his bleached hair pulled into a messy bun above his camo jacket. He held a painter’s extension pole and had a lunch pail containing glue strapped across his back.

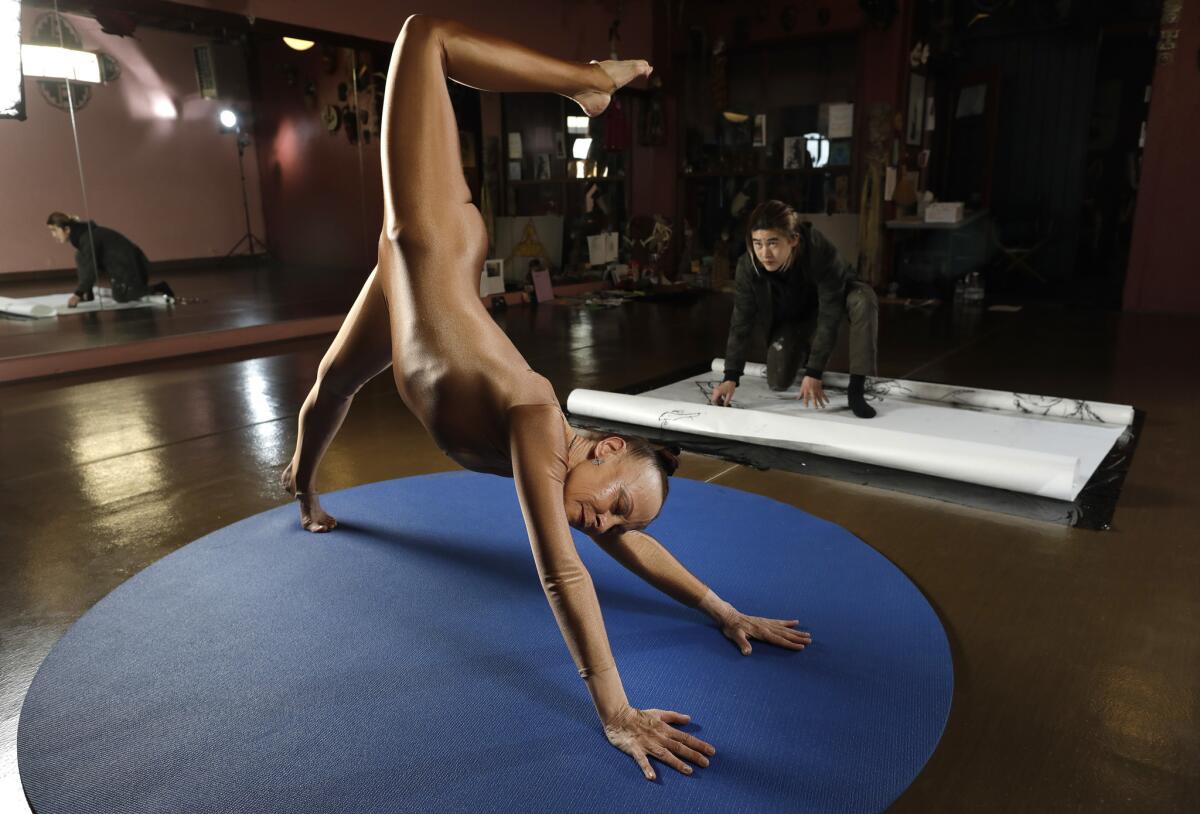

The other hands belonged to a woman in her 70s equipped with the grace of a dancer and long rolls of paper tucked under her arm in a canvas bag.

The duo began unraveling the paper, quickly pasting up a large poster. It depicted the woman, Linda Lack, a white, quirky professional dancer and movement instructor. The poster design was by the man accompanying her, a 24-year-old street artist and son of Vietnamese refugees who goes by the name Inksap.

The story of how two people of disparate worlds ended up together on that Hollywood rooftop, partners in an ongoing campaign of guerrilla art, actually started on a Monday morning in July.

Lack found a poster adhered to her dance studio of 50-odd years near La Cienega and Pico boulevards. On a plywood board covering a gaping hole created by a drunk driver, Inksap had affixed a rendering of his grandmother Tuyen fleeing with two children in tow.

Instead of being annoyed by the unauthorized art glued to her building, Lack said, she appreciated the addition. “What I got was a really beautiful piece of art, and political.”

In what Lack calls “cosmic choreography,” Inksap’s poster coincided with Trump administration immigration policies that were separating migrant families at the border. “There was really some rightness to having this put up,” she said.

Lack persuaded the construction company to carefully cut the piece out and bring it inside. She also decided to track down its creator. But when she enlisted her staff to help contact the artist by email (his address is listed on his website), he was evasive. He refused to respond or he replied under fake names.

Inksap, whose studio is just outside L.A.’s Arts District downtown, was used to fielding lots of messages responding to his work. Lack’s email was different. “I think it’s beautiful and I’m going to preserve it,” she wrote, even offering to pay him for it. “Because art is work,” she wrote.

Still, she got no answer from the artist.

“I’m an old fossil when it comes to technology, so I figured that that was it,” she said, adding that her studio’s community of students, staff, clients, collaborators and friends tried to help her connect with Inksap, but still no answer.

After months of effort one of her clients, an actress, finally gave Lack the legitimacy she needed, via Instagram. “Someone named Molly Hagan, she DMed me,” Inksap recounted. “I was like, ‘Oh, this is serious.’” He agreed to meet.

During the five-hour visit, Lack gifted Inksap with two handcrafted wooden Vietnamese boats unearthed in the belongings of Lack’s late father, who had acquired them while working on the SS Hope, a ship that provided medical care and training in developing countries. Although Lack grew up in Los Angeles and Inksap in Orange County, they came to realize just how far apart their backgrounds and experiences were.

Inksap explores his ancestry through an environmental lens by creating trash tac (artfully created dispensers hold recycled materials folded in such a way that they can be used to pick up trash) or by donning gas masks on people in his art (alluding to poor air quality and pollution in Southeast Asia). It’s an unconventional career path that never won approval from his family, and he’s had to pursue it without a formal arts education. But he found a mentor in artist Rolland Berry, eventually leaving the community college where he studied graphic design and instead adapting Berry’s silkscreen method to make collaged posters that are displayed — illegally — on walls, rooftops and electrical boxes as part of the patina of the city’s streets.

In contrast, Lack holds a master’s degree in performance and choreography from UCLA and a PhD in movement, education and healing from Union Institute & University. She likes to say she was born into a modern dance family: Her aunt was an original member of Martha Graham’s company. Lack said she trained in the Graham, Humphrey-Weidman and Cunningham techniques and danced in a Twyla Tharp pick-up company in the 1960s.

She opened Two Snake Studios and developed her own method, which she said caters to all ages and bodies, including the injured. She has a professional and personal relationship with noted choreographer Yvonne Rainer, who’s also a client, Lack said. And she has received grants from the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts and the California Arts Council.

Differences notwithstanding, Inksap and Lack said similarities abounded: the ephemeral nature of their practices, a subversion of confines and regulations. And from that first connection on a plywood panel, they have forged their own collaboration, working under the name US.

The two talked about their work while sitting cross-legged facing each other, fittingly shoe-less in Lack’s studio. Inksap’s piece “Quynh” (named for his mother) acted as the backdrop as he gesticulated with a ring-laden hand conveying the thought process behind what became their first installation.

“It’s not about me trying to encapsulate her in the way I would, but I think of encapsulating her DNA and then adding my DNA,” he said, “putting it together.” He rendered Lack in four poses that integrated her kinetic creative expression, burned the designs onto silk and pulled the screens to create the resulting artworks.

From about 8 p.m. to midnight one winter night, they put up the first round of posters at six sites between downtown and Culver City — with only a few close calls with the police.

“What he does, what we now do together on the street is performance art,” Lack said, adding that the papering often gets complemented with bits of choreography, theater and often an active audience, in some ways akin to Tharp’s 1960s Central Park performances.

However “it’s totally improvised,” she added. “You don’t know what’s gonna happen out there.”

They mention the possibility of a documentary, a mural off the 10 Freeway and an invitation to adorn a Fairfax facade. Yet with Inksap’s lack of familial support and Lack’s loss of some family members, the kinship the two have fostered seems to remain their focus.

“It’s about self-discovery — him, in terms of who he is, learning who he is and where he’s gonna set his feet down in what direction,” Lack said. “And for me, even in my 70s, it’s learning a lot about who I am. There’s something wonderful and glorious about it.”

Inksap said their unlikely collaboration is a source of new energy.

“It’s really opened my eyes to new works and how I can incorporate people who influence me,” he said, looking at Lack. “Thank you for provoking me.”

Support our coverage of local artists and the local arts scene by becoming a digital subscriber.

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.